Table of Contents

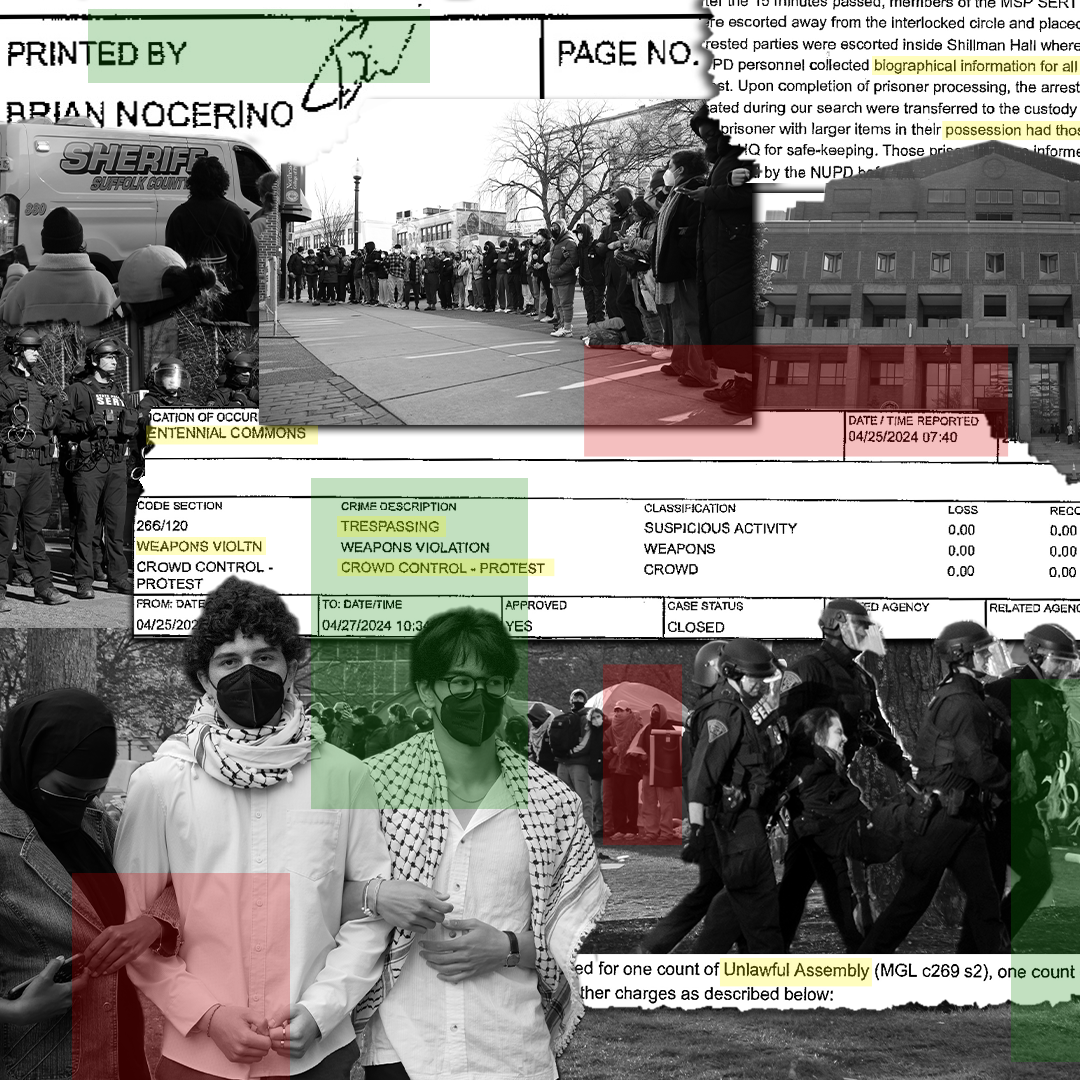

II: Who was arrested at the Northeastern encampment?

III: Legal observers, press ordered to leave the Common before arrests

IV: Protesters zip tied, taken into Shillman Hall for processing

VI: Some students say they were inappropriately touched by police, not allowed to use bathroom

VII: All legal charges to be dismissed as students seek confiscated belongings

VIII: Students placed on deferred suspension after disciplinary hearing process

One student protester said police searched her bra.

Another said police slammed him up against a wall, and then to the ground.

For hours, as a third student protester tells it, police said they were not permitted to use the bathroom. They urinated on the jail floor instead.

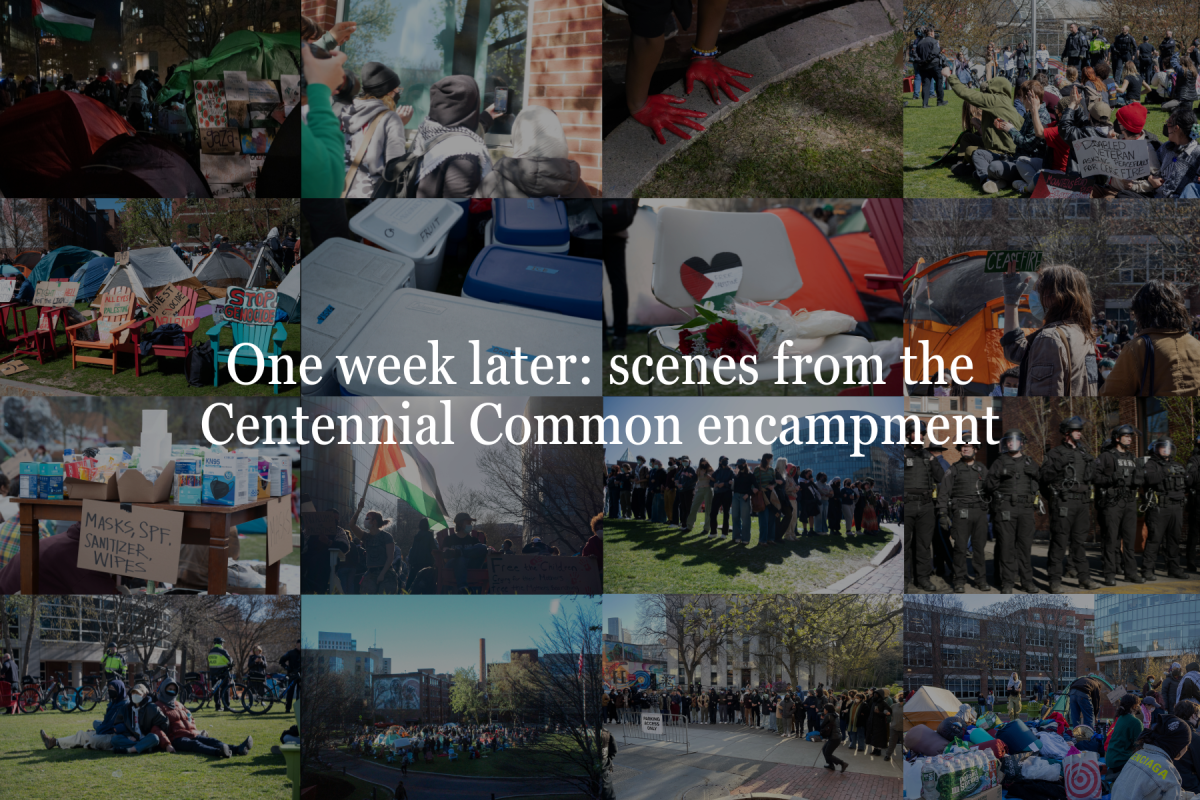

Northeastern’s pro-Palestine encampment on Centennial Common began April 25 and ended 48 hours later on April 27, when police arrested 98 protesters — the 10th-highest number of arrests made at similar encampments at over 150 universities nationwide. While arrests were made without significant resistance from protesters, multiple arrested protesters called their encounters with officers “traumatic” and, at times, “dehumanizing.”

“For the most part, the police raid was fairly peaceful,” said Maya, an arrested student who spoke at an April 29 press conference organized by arrested individuals, who asked for her last name to be withheld due to fear of jeopardizing her privacy and retaliation from peers and the school. “But there are other students who will be willing to speak out about the less peaceful aspects.”

The News spoke with more than a dozen arrested student protesters and a Northeastern professor about what they experienced as they were led away from onlookers on Centennial, processed in Shillman Hall and transported to jail in paddy wagons.

Several attorneys from the National Lawyers Guild Massachusetts Chapter, or NLG Mass, provided legal service to the arrested individuals, who were mostly charged with trespassing and unlawful assembly.

Arrested individuals’ charges have all been, or will be, dismissed in place of community service hours, said NLG Mass Executive Director Urszula Masny-Latos, and students facing disciplinary charges have started to receive sanctions from the university.

The encampment marked the tail end of numerous campus protests throughout the academic year that demanded the university disclose its financial investments, divest and cut ties from companies and institutions that do business with Israel and denounce what they called Israel’s ongoing genocide in Gaza.

Northeastern administrators and demonstrators did not meet to discuss demands. The university said protesters refused offers to meet with administrators, while protesters said the school didn’t give them “a seat at the table.” According to a statement from the university, the university opted to remove the encampment April 26, 24 hours before the police sweep occurred.

The university said the encampment was “an unauthorized occupation of university space” and participants were “in violation of the Code of Student Conduct.” It also said the encampment had been “infiltrated” by unaffiliated demonstrators and that instances of antisemitic hate speech — namely “Kill the Jews” — “left university leaders with no choice but to act.” Video footage of the protest revealed that the “Kill the Jews” remark was made April 26 by a pro-Israel counter-protester in an apparent attempt to provoke pro-Palestine demonstrators.

“From the moment the encampment was erected on Thursday morning, it was in violation of university policies,” Northeastern Vice President for Communications Renata Nyul said in a statement to The News. “In addition, those not affiliated with the university were trespassing on private property. Throughout the course of [April 25 and 26], university leaders developed a plan to disperse the encampment [the morning of April 27]. This required enlisting the support of our law enforcement partners and procuring the necessary equipment to secure the site.”

Around 7 a.m. April 27, law enforcement officers from multiple police departments cleared the encampment of protesters, arresting 98 individuals. Around 9 a.m., officers cleared the encampment of tents, flags, posters and protesters’ personal belongings.

At 12:38 p.m., Northeastern posted a statement on X, formerly Twitter, thanking law enforcement and the university’s Student Life staff for their “flawless execution” removing the encampment from Centennial. Some students told the News that they felt the statement was “tone-deaf.”

But outside of what many viewed as a “disappointing” response from the university, arrested students described multiple instances of forceful, inappropriate and confusing orders and actions from police while they cleared the encampment and detained protesters.

Encampment organizers told demonstrators not to resist and to comply with police orders, yet some said they were “manhandled.” Demonstrators said they were denied access to bathrooms, “inappropriately touched” and given conflicting information on whether they would be released if they showed a Northeastern ID.

“There were some students who were manhandled pretty roughly. Other students got off pretty lightly,” Maya said.

The university said it had no evidence of inappropriate touching by police.

“The university has conducted extensive after-action meetings, including a review of surveillance videos from the morning of April 27,” Nyul told The News. “We have found no evidence to substantiate these claims.”

While multiple Huntington News reporters were on scene during the time of the arrests, the interviews with arrested individuals provide new insight into the moments before, during and after interactions with law enforcement. As members of the press were ordered to leave Centennial, locked out of Shillman and not permitted to enter jail cells, The News cannot provide first-hand confirmation regarding some of the claims made by those interviewed. However, nearly every allegation arrested students made was corroborated by other arrested students in separate interviews.

The News can confirm the identities of all interviewed anonymous sources mentioned in this story, as well as their affiliation with the university and their presence at the encampment. Per newsroom policy, The News provides anonymity to sources if it can confirm their identity, if it cannot obtain the information through other means and if revealing the source’s identity will result in professional, disciplinary or legal retaliation or put the source’s safety at risk. Due to the sensitive nature of this story, and in order to accurately portray the experiences of those arrested, individuals determined the extent to which they would be identified.

Despite the varied interactions with police, in nearly every interview with The News, arrested students mentioned their experiences are dwarfed by the ongoing humanitarian crisis in Gaza, where Israeli troops have reportedly killed nearly 35,000 people.

“Although that was a terrible experience for me, it is nothing compared to what Palestinians in Gaza, and even in the West Bank and Israel proper, are experiencing on a daily basis under occupation, apartheid and the ruthless genocidal assault Israel has laid onto all of them,” said Kyler Shinkle-Stolar, the first protester arrested at the encampment, at the April 29 press conference.

II: Who was arrested at the Northeastern encampment?

According to the university, police arrested 98 people at the encampment, including 29 Northeastern students and six Northeastern faculty and staff. A Northeastern University Police Department, or NUPD, report obtained by The News listed 55 arrestees as having “no affiliation” with the university; 29 Northeastern students; eight alumni; one “contractor” and five staff and faculty members.

In response to an inquiry from The News regarding the university’s definition of affiliation with the school, Nyul said, “Alumni are not subject to the Code of Student Conduct. They have an affinity for Northeastern, but not affiliated the same way students and employees are.” Multiple members of the Northeastern graduating Class of 2024 were listed on the NUPD report as alumni rather than students.

Nearly all arrested individuals listed their residencies in Boston or Massachusetts, and all but 19 were under 25 years old. The News’ analysis also revealed that many arrested demonstrators appeared to attend neighboring universities and colleges, including Boston University, Massachusetts College of Art and Design, Simmons University, Berklee College of Music, the University of Massachusetts Boston, Suffolk University, Tufts University, Harvard University and Wellesley College.

In a separate statement on X, the university said the encampment was “infiltrated by professional organizers with no affiliation to Northeastern.”

The News was unable to verify the number of professional organizers present on the day of the arrests, but can confirm the presence of members affiliated with the Party for Socialism and Liberation, and non-Northeastern chapters of the Young Democratic Socialists of America and Students for Justice in Palestine throughout the 48-hour duration of the encampment.

Nyul said the university made its determination that unaffiliated organizers had “infiltrated” the encampment based in part on social media activity.

“Social media posts during the encampment clearly demonstrated that outsiders were both infiltrating the encampment and orchestrating the activities of the protesters,” Nyul told The News in response to a question about how the university determined outside organizers were at the encampment. “The arrest data also revealed that the vast majority of the protesters were not affiliated with Northeastern.”

Ninety-three protesters were charged with one count of unlawful assembly and one count of trespassing. Four were charged with resisting arrest for “physically pulling away” while officers were attempting to place them in custody and one protester was charged with carrying a dangerous weapon on school grounds after police located one folding knife on him and another in a bag that belonged to him at the encampment.

The Massachusetts State Police, or MSP, initially reported that approximately 102 individuals were arrested, four more than the 98 arrested recorded in the NUPD report.

In an email statement, a spokesperson for MSP told The News that the reason for the discrepancy between the NUPD report and State Police number was because the latter said it was “approximately” 102 individuals.

III: Legal observers, press ordered to leave the Common before arrests

Protesters braced for a police sweep of the encampment the night of April 26, when the unaffiliated student group Huskies for a Free Palestine, or HFP, reported receiving “credible information” about the university hiring a moving company to clear belongings from the encampment. Around 4 a.m. the next morning, protesters formed a human chain as police started arriving on campus, but police did not begin sweeping the encampment until three hours later.

In the days and hours prior to the police sweep, multiple university leaders, including Vice Chancellor and Dean of Students Chong Kim-Wong and Senior Director of Public Safety and Deputy Chief of Police Ruben Galindo, told demonstrators that they must leave the encampment, declaring it an unlawful assembly and saying it would be dismantled.

“Many of the protesters took this opportunity,” the university said on a web page about the encampment.

The News could not confirm how many protesters left the encampment prior to the police sweep, but the number of present demonstrators was significantly smaller the morning of April 27 than at previous times throughout the encampment.

At about 7 a.m., police officers and troopers from NUPD, the Boston Police Department, or BPD, and MSP began deploying around Centennial, encircling the encampment. The university told The News about 120 officers were present — approximately 50 from NUPD, 50 State Police troopers and 20 BPD officers.

About 30 minutes later, officers began tearing down the barricade demonstrators had formed with Adirondack chairs, flipping over tents and arresting protesters, most of whom were still chanting as they were arrested.

Before police began arrests, two Olympia moving trucks — one near Ryder Hall and one on Leon Street — brought metal barricades which Olympia employees set around the perimeter of the Common. The trucks were also then used to load up the Adirondack chairs from the protesters’ barricade.

Police ordered all individuals, including press, medics and legal observers, to leave Centennial.

Several Huntington News reporters were told to leave the barricaded area under threat of their “student status.”

Boston police ordered at least five legal observers, who had monitored the encampment since it was established, to move outside of the barricade.

Police made observers move “as far from the scene as possible so [the police] would not be easily visible,” Masny-Latos said.

Legal observers are legally trained volunteers — in this case, volunteers from NLG Mass — who monitor and document police engagement with protesters. Twenty-one NLG legal observers oversaw the Northeastern encampment in shifts, Masny-Latos said. While officers from NUPD initially told the observers they could stay in an easily visible area, Masny-Latos said Boston police ordered the observers to move further away.

“BPD officer[s] completely overruled the Northeastern cops and forced NLG legal observers off the grounds where the arrests happened,” Masny-Latos said. “It was obvious that on the Northeastern campus, BPD cops had control.”

The Boston Police Department did not respond to questions from The News about why they ordered legal observers and media to move further from Centennial.

Before police made contact with protesters, a protester on Centennial, who later identified herself as Chelsea Penetra during the press conference, fell to the ground with an apparent injury while demonstrators were chanting. Police prevented the already-removed medics from coming inside the barricades to provide medical assistance. Firefighters later arrived at Centennial and spoke with Penetra, who appeared to be OK, The News previously reported.

At the April 29 press conference, Penetra appeared in crutches with a knee injury, clarifying that she was not injured due to police action and was also not arrested, but condemning the university’s response.

“As someone who needed a medic during the arrests, it was despicable and deplorable that the university said they were doing this for community safety,” she said.

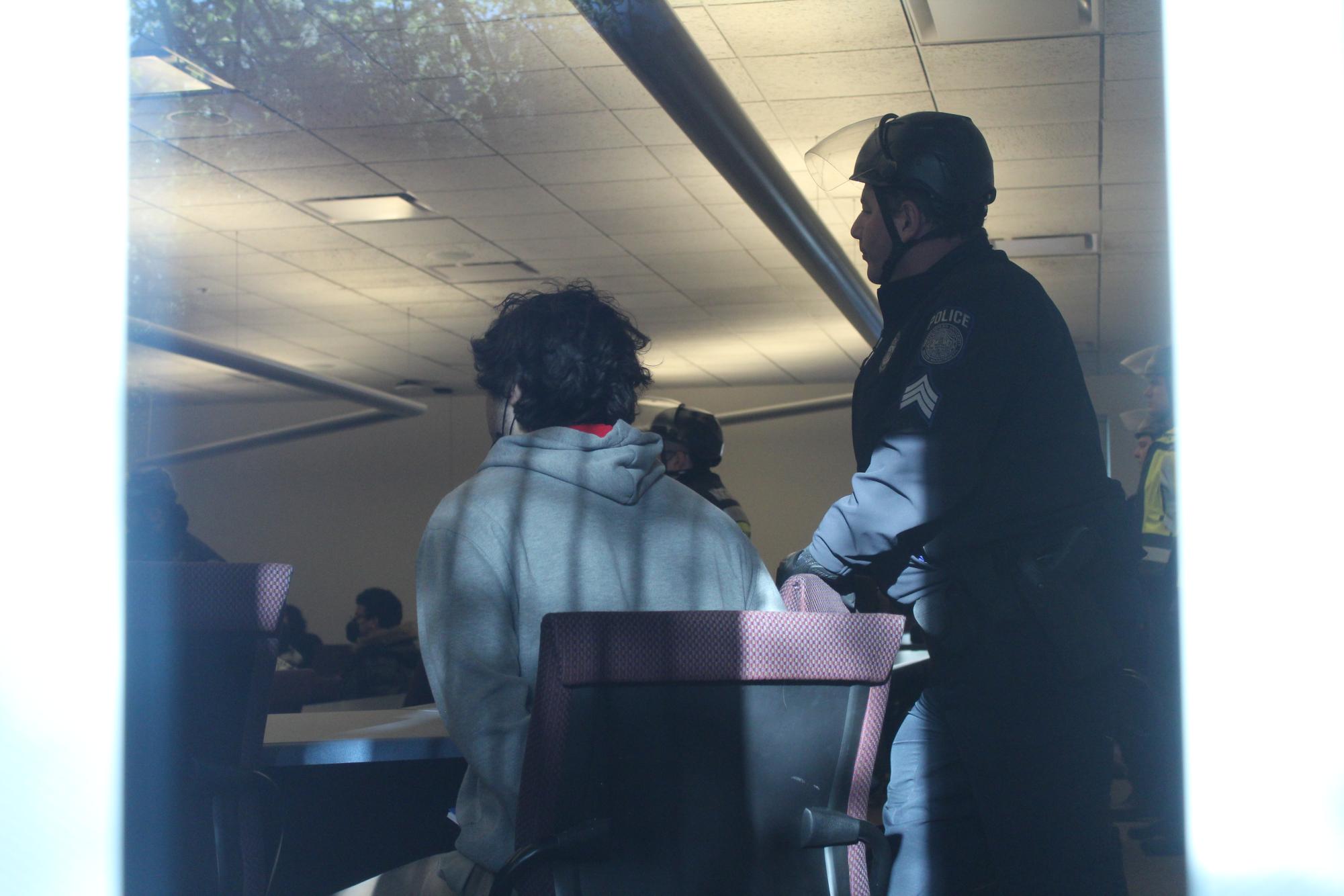

IV: Protesters zip tied, taken into Shillman Hall for processing

When arrests began at approximately 7 a.m. April 27, protesters did not appear to resist, though one protester appeared to be carried into Shillman by multiple officers. Students said they were detained one by one.

At the request of NUPD, MSP was the arresting body on Centennial, removing protesters from the area, the university said.

One arrested student, who was granted anonymity due to fear of jeopardizing their privacy and retaliation from peers and the school, described officers’ removal of protesters from the human chain they had formed around the encampment as “ripping” their interlinked arms apart.

Jordan Korgood, an arrested Northeastern graduate student, said shortly before arrests began, police officers circling the encampment warned protesters it was their “last chance to go” or they would be arrested.

“I said, ‘I’m a tuition-paying Northeastern student,’ and they’re like, ‘You’re being arrested for trespassing,’” Korgood said. “And then a cop grabbed my arm, he said ‘Hands behind your back.’”

Korgood said the officer placed the zip tie on top of multiple bracelets they were wearing.

“I immediately knew something was wrong because my fingers started buzzing and were tingling,” Korgood said.

After being seated on the curb of Centennial for about 15 minutes, Korgood said they lost all feeling in their right hand and called another officer over. The officer used shears to cut the zip tie off them and informed Korgood that they had lost circulation in their hand for a few minutes, Korgood said.

Other students said police dismissed their complaints that their zip ties hurt and inflicted further pain.

“They kept tightening the ties even after I told them that they hurt,” said an arrested student, who was granted anonymity due to fear of jeopardizing their privacy and retaliation from peers and the school.

Sahra Ahmed, a rising third-year bioengineering major who was arrested, said an officer “grabbed [her] arms” while she was zip tied and escorted her into Shillman. Protesters outside of the barricaded area stood close to Shillman, yelling out to arrestees asking for their names and birthdays for jail support. When Ahmed yelled back her information, she said the officer escorting her showed aggression.

“I gave my name and my birthday, and the officer who was detaining me grabbed my arms that were already tied behind my back and lifted them up towards my upper back, and it hurt,” Ahmed said. “I was like, ‘Why are you doing this?’ And he accused me of resisting arrest for simply giving my name and birthday.”

Once inside the main hallway in Shillman, Ahmed said she was transferred over to another officer, who she said was also acting aggressively. She told the officer he was hurting her arms, and when an arrestee in front of her asked, “Why are you hurting her?” he was “thrown onto the ground.”

“He was pushed to the wall and then thrown onto the ground by three officers, and then they just surrounded him,” Ahmed said.

Matan, the student who was thrown to the ground, requested that his last name be withheld due to fear of jeopardizing his privacy and retaliation from peers and the school. He believes police treated him with such force because he defended Ahmed and felt “violated” after the interaction.

“It happened like a second after [I yelled to officers],” Matan said. “I could see that they were hurting her. I was like, ‘What the fuck?’ And then they slammed me.”

Matan was one of the four arrested individuals charged with an additional count of resisting arrest, according to the NUPD report.

“While being escorted to prisoner processing following his arrest, [Matan] pulled away from officers and had to be guided to the ground to prevent possible escape,” the report reads.

Matan said he made several taunting remarks to police officers throughout the encampment and during arrests, which he said may have unjustly contributed to the extent of force officers used on him.

Once moved inside Shillman room 101, a lecture hall that police used as a “field prisoner processing area” per the NUPD report, arrested students said they were heavily searched and their belongings were placed in plastic bags. Then, police took pictures of the protesters against a blackboard, arrested individuals said.

After MSP made the arrests, it transferred custody to NUPD in order to process arrests in Shillman.

Detained demonstrators told The News police asked for Northeastern IDs and government IDs, and for students to fill out a form with their addresses for potential court summonses.

Students also said police issued numbered stickers that were placed on arrestees’ hands according to the order in which they were processed. The numbers were used to refer to individuals until they were released from the jail.

Once individuals were processed, NUPD transferred custody to the Suffolk County Sheriff’s Department to transport the individuals to jail.

Students were then placed in Sheriff’s Department paddy wagons, which they said were small and cramped.

“They would cram, like seven, eight of us in there,” an anonymous arrested student said.

“There’s two rows of benches, no windows, but also the ceiling is slanted in and sirens blaring the whole time,” Matan said.

An anonymous arrested student said that some arrestees were stuck in the paddy wagons for a prolonged amount of time after remaining protesters formed a human chain outside of Shillman’s parking lot exit, which blocked the vans from leaving and forced an alternative route.

The anonymous student said they believe police used relatively limited force during arrests due to backlash after the “violent arrest” of 118 protesters at Emerson College two days before.

After police swept the encampment at Emerson,“[city crews had to] power wash the blood of students off the sidewalk. So I think [police] were cautious about not having another PR disaster like that. I think we got lucky in terms of physical force,” the student said.

V: Arrestees say Northeastern did not release all those who showed Northeastern IDs, contradicting university statement

In a statement to The News following arrests the morning of April 27, Nyul said students who produced valid Northeastern IDs were released and would face disciplinary proceedings within the university, but no legal charges, and that those who refused to disclose their affiliation were arrested.

“Those who refused to leave were detained by police. Students who showed a valid Northeastern ID before arrest were released and will face disciplinary proceedings in accordance with the Student Code of Conduct. Those not affiliated with Northeastern, or who refused to show identification, were arrested,” Provost David Madigan and Chancellor Ken Henderson reiterated in a joint statement sent to the Northeastern community April 29.

The university’s statements, as well as messaging directed to protesters throughout the encampment, conveyed that students who showed identification would be released without legal charges. The testimonies of multiple arrested students who were taken to jail and legally charged, however, along with later clarification from Nyul, show that only students who showed identification before arrests were released. Nyul told The News May 24 that only students who showed Northeastern IDs before police applied zip ties were released.

“Per the State Police’s orders, once individuals were detained with zip ties, they were under arrest,” Nyul said in an email statement. “Any individuals released after being zip tied received a summons to appear in district court. Before being arrested every person was given repeated opportunities to leave the area and avoid arrest. Including immediately before the zip ties were applied.”

Several protesters said that messaging from police officers regarding showing a Northeastern ID were confusing or conflicting. While many students said officers told them they would be released if they showed a valid Northeastern ID, several reported showing the ID and still being arrested, adding that the offer was not upheld for everyone.

“[Before arrests started], police were walking around, saying, ‘If you’re a Northeastern student and you show your ID, you won’t get arrested,’” an anonymous arrested student said.

One arrested Northeastern professor, who was granted anonymity due to fear of retaliation from peers and the school, said she was originally told by police that if she showed her ID she would be released.

“My understanding about what happened was that they had released some individuals who had showed their ID,” she said. “And I was personally told by a police officer that if I did show my ID, I would be released.”

She said she mentioned this to an officer, who “investigated” and returned, telling her, “‘No, that must have been misinformation. No one is being released even if you’re Northeastern-affiliated.’”

“So what I believe happened is for some reason they changed their mind,” she said.

Ahmed said she told officers that her Northeastern ID was in her pocket when she was detained in Shillman Hall. She said officers saw her ID and still arrested her.

“Northeastern did say that if you did show your Northeastern ID that you wouldn’t be arrested. But I did in fact show my Northeastern ID … and I was still arrested, so I think that wasn’t completely accurate,” Ahmed said.

Maya, who was offered the opportunity to show her Northeastern ID after being zip tied, also said police made conflicting statements.

“To clarify, not all students were given that option,” she said. “I was in a group of students who were given that option: that if we showed our NU ID, we could walk away without being arrested, they would un-zip tie us. There also were several students who were not given that option at all. So they weren’t consistent in their messaging or their offers to students.”

Korgood also said they showed their Northeastern ID and told officers they were a graduate student, but were still taken to jail.

“Northeastern is claiming that they did not let anyone [who showed a Northeastern ID] be fully arrested and sent to jail who identified themselves and complied with orders,” Korgood said. “This is a blatant, blatant lie. This was a temporary policy that they had for the first 40 people.”

One anonymous student, who said police searched her bra in Shillman, also said she was put into a paddy wagon and taken to jail despite officers finding her Northeastern ID when they searched her.

Archie, an arrested student who asked that his last name be withheld due to fear of jeopardizing his privacy and retaliation from peers and the school, said that after being zip tied and escorted into Shillman, a female officer told him, “If you show me your NU ID, I’ll let you walk free.” To her offer to be released, Archie replied, “I’m good.” The officer took a picture of his Northeastern ID at the counter of the Shillman Dunkin’ and proceeded to escort him into the lecture hall.

He added, however, that an arrested student in front of him by the counter was given the same instructions and told the female officer she’d like to show her Northeastern ID and be released. Archie said a senior officer walked over and told the officer it was “too late” before escorting the student into Shillman 101.

One student who spoke with The News, who was granted anonymity due to fear of jeopardizing his privacy and retaliation from peers and the school, said he believes he was one of the last students who was allowed to show his Northeastern ID to be released.

“I was told that if I had my [Northeastern] ID on me, that I could be let out, essentially, without having to go to the jail itself,” the student said. “So I presented them with my NU ID and my regular ID and filled out a form that was basically just my address for them to send me my court summons.”

“That’s when the lieutenant comes in and says, ‘No, Northeastern rescinded that deal, it’s not happening anymore,’” the student said. He said he was eventually let go after telling police he felt he had been “lied to.”

VI: Some students say they were inappropriately touched by police, not allowed to use bathroom

While being searched in Shillman and processed at Nashua Street Jail, multiple arrested individuals said that they were “inappropriately touched” by police.

One arrested student, who was granted anonymity due to fear of jeopardizing her privacy and retaliation from peers and the school, said when she was searched in Shillman, a female police officer put her hand in her bra to retrieve her Northeastern ID and inhaler. The student said she told officers multiple times that she would be “more than willing” to give them over if they could take off her zip ties.

“I asked the person next to me, ‘Oh, I wonder how I’m going to get my ID because my ID is under my shirt,’” the student said. “I had my inhaler and my ID in my bra so I wouldn’t lose them. And an officer made a really crude joke, and he was like, ‘Oh, don’t worry, we have ways of getting in there.’”

But another officer told her that this was “for their safety and [hers]” before lifting up her shirt in a room full of people, the student said.

“Thankfully, I don’t think anyone saw because my back was behind everyone and my jacket was pretty big,” the student said. “And when she couldn’t find my ID, she thought it was a good idea to, instead of lift up my shirt … dig from above. I was really uncomfortable. And I was trying to disassociate, just go to another place mentally. She was like, ‘I’m sorry. I feel like I’m violating you,’ and I was like, ‘Most definitely, yeah, this is most definitely a violation.’”

Matan was also searched in Shillman and reported “invasive” search tactics, saying officers “grabbed [his] crotch” while patting him down.

“They did the standard pat down, but then they were touching my crotch area, too. And they were grabbing, supposedly to feel for any dangerous weapons. One of them put his hands under my belt against my skin and was pulling under the underwear all around,” he said.

At Nashua Street Jail April 25, Shinkle-Stolar was reportedly strip-searched, which protesters cited as “inappropriate touching” at the press conference.

Several protesters also said they were not allowed to use the bathroom throughout many hours of processing in Shillman and the jail — which they say was exacerbated by being awake and chanting on Centennial since 4 a.m.

Multiple students told The News that, after police repeatedly denied requests to use the bathroom while in Shillman, two individuals relieved themselves in the paddy wagons on the way to the jail. The Suffolk County Sheriff’s Office did not respond to The News’ questions seeking verification of the incidents.

Korgood said that despite telling officers multiple times that they had to use the bathroom, police repeatedly denied their requests. They said they eventually had to relieve themselves in the corner of the holding cell they were put in.

“I had told officers five times at this point that I needed to pee or I would pee my pants,” Korgood said. “So [other arrestees] made a wall around me, and I pissed in the corner of that first room in the jail.”

Korgood, who identifies as Jewish, said they were observing Passover and had not eaten since Seder the night before. When they were being processed, they felt faint and asked the police to take off their zip tie so they could eat a protein bar they had in their pocket.

Police initially refused the request, Korgood said, but eventually undid their zip tie and allowed them to eat the protein bar. After, Korgood said they had to sign a form that said police would not provide further “medical assistance.”

Korgood also said that, despite telling officers multiple times they identified as female and went by they or she pronouns, officers routinely called them “buddy” and referred to them as “he” and “sir.”

Arrestees were separated by gender at the jail. Two students in the male holding cell said that one person “started throwing up bile and almost passed out” after “looking pretty pale for a while” due to police not giving arrestees water. The Suffolk County Sheriff’s Office did not respond to The News’ questions asking to verify this information.

Several students said they were not given water in Shillman and were only given water at the jail after repeated requests, adding that female arrestees were given a jug of water first and male arrestees were given the jug after.

State Police and BPD directed questions about the encampment — including allegations of innapropriate touching — to Northeastern, saying NUPD was handling the situation on campus. The university told The News it had “no evidence” of the claims being made by arrestees.

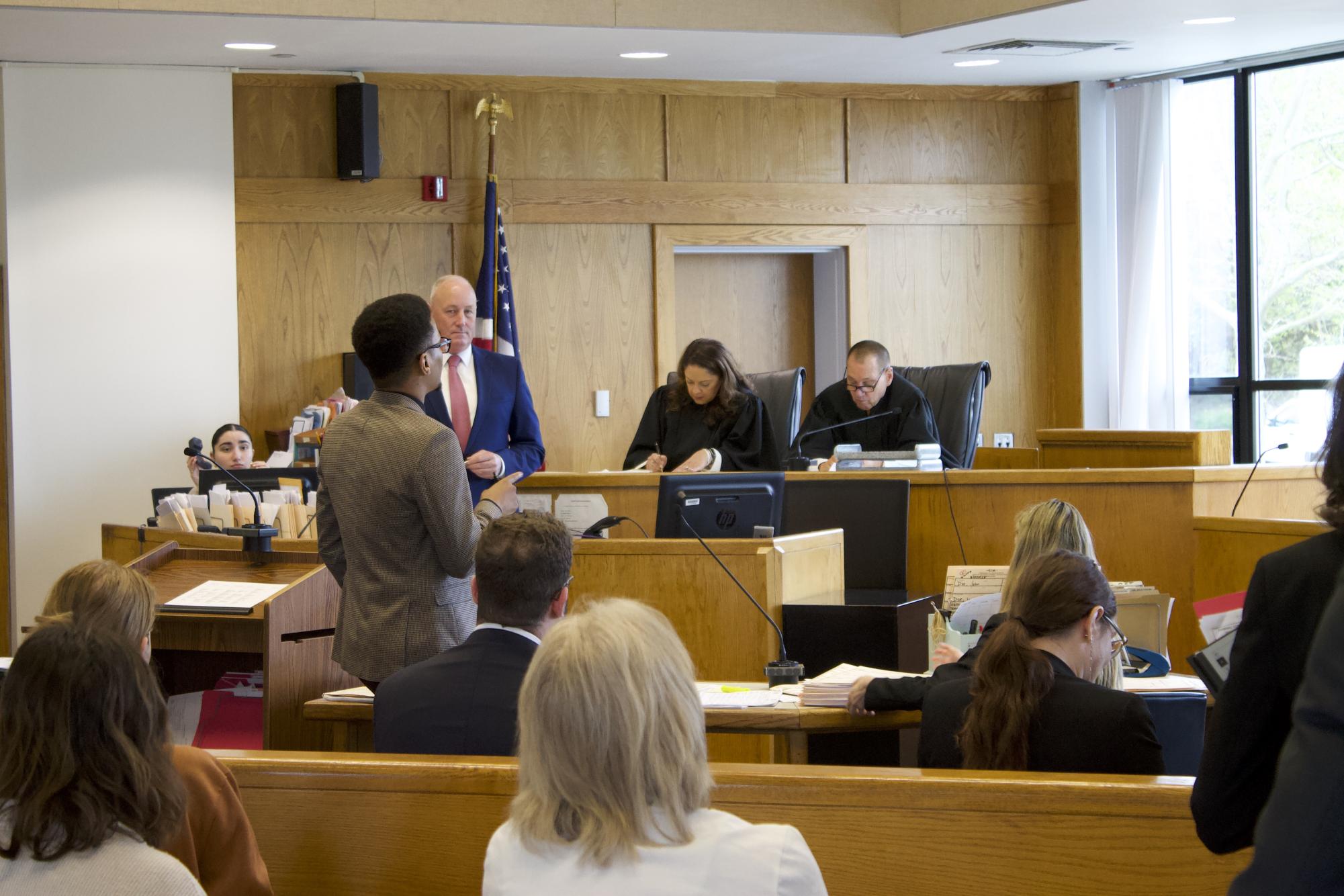

VII: All legal charges to be dismissed as students seek confiscated belongings

Shinkle-Stolar, who was apprehended by NUPD on the first day of the encampment, was the first person to be arrested and arraigned at Boston Municipal Court in Roxbury. At his arraignment April 29, the charges against him were dismissed and he was given 20 hours of community service.

Over the course of a little more than a week, arraignments for the rest of the individuals arrested at Northeastern would have similar outcomes.

Attorneys from NLG Mass worked with 105 individuals police brought to Nashua Street Jail April 27, Masny-Latos said. It was not immediately clear what the cause of the discrepancy between the 98 arrested individuals and the 105 who worked with the NLG was.

Individuals were brought into the jail’s holding cells and were all eventually released on roughly $40 bail commissioners fees paid by the Massachusetts Bail Fund, Janhavi Madabushi, director of the Fund, told The News.

The Fund is an abolitionist, non-profit organization financed by individual donations that pays pretrial cash bail to release from jail incarcerated individuals who cannot afford it, according to its website.

Throughout the erections and police sweeps of encampments across Greater Boston, the Fund paid bail for several arrested individuals and provided updates on encampments and the status of those incarcerated on its X account. Madabushi, who was arrested at the Northeastern encampment, said the Fund was in contact with the Massachusetts chapter of the NLG to facilitate the payment of the bail commissioner fees for those arrested at Northeastern.

Madabushi said the Fund paid for all 98 individuals arrested at Northeastern, a total of $3,920.

By 4:10 p.m. April 27, all arrested individuals were released, according to an NLG Mass post on X.

Arraignments for demonstrators arrested at Northeastern started April 29 and continued through May 7, and Masny-Latos said all charges against those arrested at Northeastern have already, or will be, dismissed.

In a May 13 email to The News, Masny-Latos said there were four cases that had yet to be dismissed, but that “they will be dismissed as well.”

Arrested individuals are required to stay off Northeastern property except for official business — including education or employment — and to complete between 20 to 40 community service hours with 501(c)(3) non-profit organizations depending on each individual’s respective charges.

If these individuals avoid future offenses over the next six months, they will not be required to return to court.

“All charges have been (or will be soon) dropped because there was no evidence of serious criminal behavior on part of the arrestees,” Masny-Latos said in an email to The News. “Arrested people did not do anything illegal that called for arrests. They were arrested because the school administrators wanted to remove them from campus and end the encampment.”

Masny-Latos said that with so many arrested protesters in the area, the NLG Mass chapter’s priority is to make sure all arrested individuals are processed with representation. Then, she said, they will look into specific allegations of misconduct.

“Our priority right now is to make sure that all those arrested at Northeastern have proper legal advice and representation and have everything they need,” Masny-Latos said. “Our goal is to have all charges dismissed, but our criminal defense attorneys are also preparing for any future court appearances. There [are] many other legal issues that the students and faculty members are bringing to us — related to immigration and employment laws — but these issues will be addressed later when the criminal cases are resolved.”

Meanwhile, arrested individuals are still working on retrieving their belongings left behind after the police sweep. According to the NUPD report, “non-valuables” and perishables — including tents, blankets and food — were disposed of after the arrests. All other items were transported to the NUPD station at 716 Columbus Ave., now 1135 Tremont St. as 716 Columbus is under renovation, where students can pick them up.

“Only if you give your name and your phone number [may you retrieve belongings from NUPD],” one arrested student protester said.

In the immediate days following the arrests, some students reported that essential items like medications and electronic devices were in NUPD custody. Some students feared retrieving their belongings would further aid the university in issuing disciplinary action.

“People are scared to face further repression, and that the university will use this as a tool to [discipline] people and identify who was a student and who wasn’t,” Maya said.

The university said “most” items have been returned to owners but did not address claims that some personal belongings were missing.

“All individuals at the unauthorized encampment were advised that any items left behind would be considered abandoned property,” Nyul told The News. “The items NUPD collected from Centennial quad are accounted for and most of it have been returned to the owners.”

One member of HFP, who was not arrested and was granted anonymity due to fear of jeopardizing their privacy and retaliation from peers and the school, is one of several members who has been helping arrestees retrieve their belongings from NUPD. The student said they’ve been “providing advice to make sure no one is intimidated or deceived into jeopardizing their safety.”

While the majority of arrested students have attempted to retrieve their belongings from NUPD, the student said many had their bags returned with missing items, including valuables like wallets and laptops “from bags that were clearly opened and searched.”

“A majority of belongings have not been retrieved because police have indiscriminately disposed of most of them,” the student said.

In response to the missing belongings, the student said arrested individuals have “repeatedly asked NUPD” and “made multiple visits to the stations,” but that NUPD has “been unwilling to help and provided no recourse.”

The university did not address questions from The News regarding students’ allegations that NUPD stole certain items.

VIII: Students placed on deferred suspension after disciplinary hearing process

Following disciplinary hearings overseen by the university’s Office of Student Conduct and Conflict Resolution, or OSCCR, multiple students arrested at the encampment have been placed on deferred suspension, the most serious formal warning issued by the university, according to letters shared with The News by disciplined students.

The letters show OSCCR found the students in violation of several policies laid out in the Code of Student Conduct after the completion of disciplinary hearings that took place over the past several weeks.

The university “does not disclose the outcome of individual disciplinary proceedings” due to privacy policies and federal law, according to a FAQ page on the university-run media outlet, Northeastern Global News.

At least one student received the letter notifying them of the disciplinary action in early June. The deferred suspensions are effective immediately and will end at the end of the spring 2025 semester, when students will then be placed on disciplinary probation, a less severe form of warning issued by the university, according to the letters.

Disciplined students are also required to write an essay of at least 1,000 words reflecting on their actions, the rationale behind the university’s demonstration policies and how their “behaviors impacted others.”

Students on deferred suspension are allowed to take classes, live in residence halls and participate in university events. They are barred, however, from holding leadership positions in clubs and may be “limited in their ability to attend University programs, including those outside the country.” If students are found responsible for additional code violations during the period of deferred suspension, they “may be suspended or expelled.”

The News could not confirm the number of students placed on deferred suspension or if students received other punishments, but HFP announced in a May 16 Instagram post that 30 students in total are being charged with violations of the Code of Student Conduct for their participation in the encampment.

A student who spoke with The News and who received a letter first notifying them of disciplinary action from OSCCR May 8 said violations included disorderly conduct, disruptive gatherings, endangering behavior, failure to comply and violation of university policies.

The HFP Instagram post stated that other students were charged with similar violations.

The letter directed recipients to contact OSCCR personnel to schedule an administrative hearing. This type of hearing is used for the most minor punishments issued by OSCCR, including a written warning, disciplinary probation or deferred suspension, according to the student handbook.

Some students charged with Code of Student Conduct violations were not detained or arrested, according to the HFP Instagram post.

The group also said some of those charged had “already been suspended without hearings” or faced expulsion due to past OSCCR charges. The News could not confirm this information.

The Code of Student Conduct holds that students must “follow reasonable directions of University personnel.” Many protesters, including students charged with failure to comply with the Code of Student Conduct, refused to leave the encampment after administrators informed students the encampment was in violation of university policy.

The disorderly conduct charge accuses a student of acting in a way that was “disorderly or disruptive” and “negatively affect[ed] the campus community, the neighborhood and/or community members.”

Disruptive gatherings, according to the university, constitute gatherings that garner a noise complaint, police response, are disruptive to neighbors or are “excessive [in] attendance beyond what is safe/reasonable.”

Students who are charged with endangering behavior allegedly acted in a way that was a “threat to self or others, or to the proper functioning of the University.” This includes threats, bypassing security measures, using an item to cause fear and intimidation or injury to another person.

The hearing includes the student and hearing administrator, with no outside parties except for hearing advisors — if requested by the student — allowed. After the hearing, a decision letter is usually issued after 10-15 business days, according to the handbook.

While many have called on the university to drop the charges against students, Nyul said the university must uniformly enforce its Code of Student Conduct.

“One of the strengths in Northeastern’s management of this year’s campus events has been the uniform application of the Code of Student Conduct,” Nyul told The News when asked why the school was pursuing disciplinary charges. “Rules are enforced equally across the board.”

At nearby schools, the enforcement of disciplinary action and legal charges vary.

At Emerson College, where 118 arrests were made April 25, President Jay Bernhardt announced in an April 28 letter that the university would not take disciplinary action against arrested students and would discourage the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office from pursuing charges.

In efforts to delay or altogether avoid involving law enforcement, schools including the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University issued suspensions to students who did not leave the encampments after administration-proposed deadlines. Revoked access to residential halls and campus buildings proved difficult for suspended students.

Harvard administrators and protesters came to an agreement to end the encampment May 14 after at least 22 students received suspension notices. Interim President Alan Garber said he would expedite reinstatement procedures for suspended students. Harvard’s governing board elected to bar 13 graduating seniors who participated in the encampment from receiving their degrees on time due to disciplinary charges — a controversial decision which prompted a mass walkout at its commencement ceremony.

Arrested Northeastern protesters acknowledged that they were given multiple warnings from administrators and police to leave or else they would be arrested and disciplined. Many said they were willing to be arrested for the sake of their demands.

“The purpose of the encampment was for our demands to be met: disclosure. Divestment. Denounce,” Ahmed said. “And none of those things were met. None of those things were even given a bat of the eye by admin. So, of course, we wanted to keep the encampment up for as long as we could until admin took our causes seriously because I honestly think that they don’t think that we are serious about our demands, and we absolutely are.”

In the provost and chancellor’s joint statement to the Northeastern community, the university said it had tried to negotiate with demonstrators several times to no avail.

“Numerous attempts by our Student Life staff to engage directly with students were repeatedly rejected,” the statement said.

But students held that they were never offered the opportunity to negotiate with the university.

“Northeastern’s administration has made no impression of being even open to negotiating with its community,” said August Escandon, an arrested Class of 2024 graduate, at the press conference.

A media liaison for HFP told The News that the university “never gave [HFP] a seat at the table.”

Nyul pointed to the provost and chancellor’s statement when The News asked about HFP’s claims that the university did not engage in fair negotiations.

With commencement, which was marked by several pro-Palestinian demonstrations, and the spring semester in the rearview, it’s unclear what future pro-Palestinian activism may look like at Northeastern in the coming semesters. But students have reiterated that demonstrations will persist as long as the war goes on or the school continues to reject demands, and recent reports indicate that Israel plans to continue its military ground operation in Gaza through the end of this year and into the next.

Interviewed individuals said they believe organizing will continue in fall 2024, but outside of an HFP-organized Nakba Day Memorial May 15 — where attendees “honour[ed] Palestinian martyrs” killed in the 1948 Nakba, according to an HFP Instagram story post — and various petitions, written statements and social media posts, on-campus organized actions have largely ceased.

“Many of us have visibly shown that we are willing to sacrifice our personal freedoms, our personal resources, for the Palestinian people,” Escandon said. “We believe that the other students at Northeastern have seen this, have heard this and will be on the right side of history.”

“I know that what the government of Israel, that what the IDF is doing to the innocent people of Palestine is not Jewish and cannot be justified in my name, and I will do anything in my power, even if it means getting arrested again,” Korgood said.