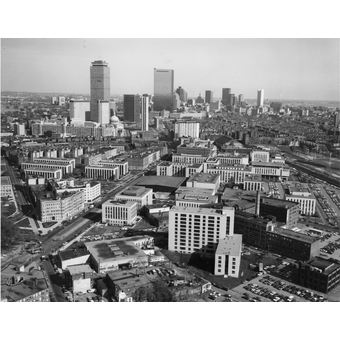

From its founding in 1898 until the late 1990s, Northeastern functioned as a commuter school, with the majority of the student population traveling to and from campus every day. Cluttered with parking lots and lacking a campus feel, Northeastern’s leaders eventually realized its identity wasn’t enough to maintain a competitive edge over neighboring universities.

So, in the 1980s, university officials contracted an architecture firm, Sasaki Associates, Inc., to investigate what they needed to change. The result was a 44-page long development plan for the next decade and the first institutional master plan for the institution.

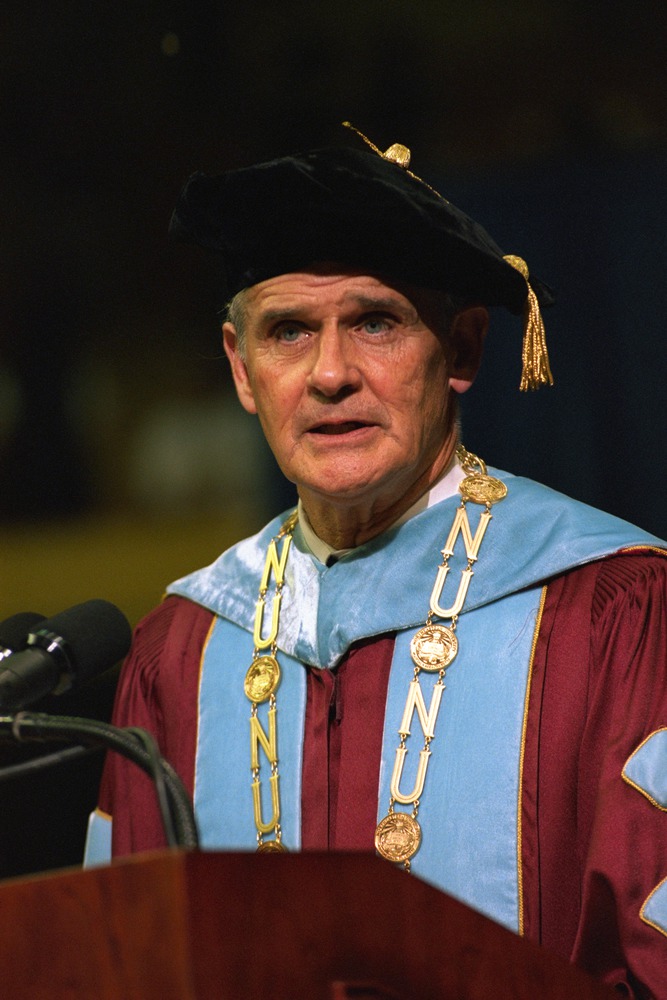

In June, Northeastern released its 2024 institutional master plan with goals and planning objectives for the next decade — most notably the demolition and redesign of Matthews Arena. Northeastern released two other institutional master plans in 1999 and 2013. However, the original “Master Plan” came to be in 1987 under former President John A. Curry’s leadership.

It is unclear whether the 1987 plan was submitted for approval to the Boston Planning and Development Agency as the institutional master plans are today.

Northeastern Archives has preserved multiple drafts of the first master plan, and the final draft was published in 1987 and was written by Sasaki Associates in collaboration with Northeastern officials. The 44-page draft is followed by a “draft inventory report,” a supplementary document created in 1986 that adds more details to the Master Plan about the state of the university and new ideas for the future.

The plan encapsulates not only what the university looked like at the time it was written, but also what Northeastern’s main goals were regarding renovations and expansion.

The university’s growth strategy took the form of two major elements, The News found through a review of the plans kept in Northeastern’s archives.

A “symbolic or special presence”

Throughout the plan, Northeastern officials and the planners from Sasaki Associates stressed the importance of establishing the university’s campus as a unique presence amid the urban neighborhoods of Boston.

“Northeastern University, by sheer mass and size, is a major entity within the urban neighborhood; however, the campus lacks the symbolic or special presence typically associated with major universities,” page 19 of the plan reads.

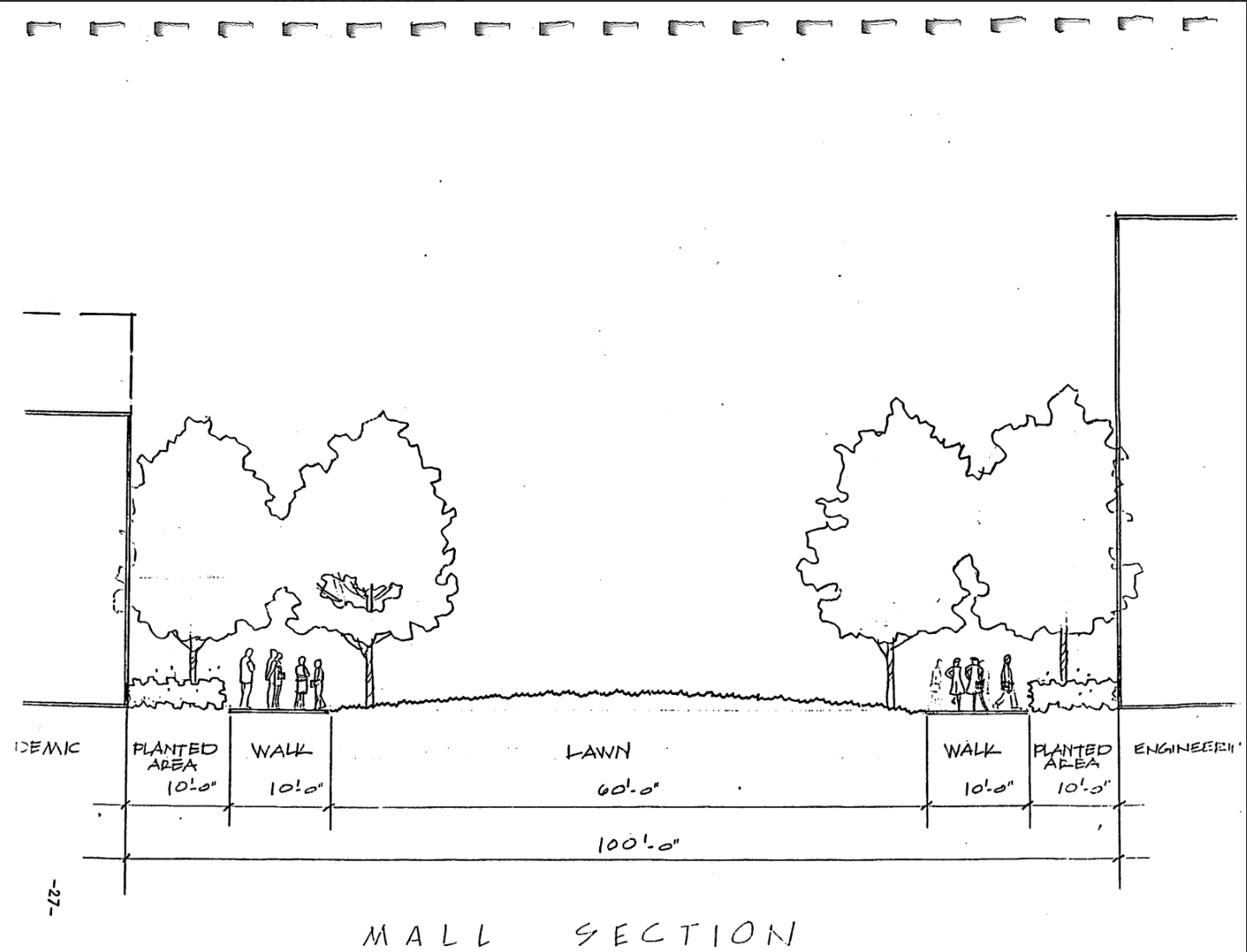

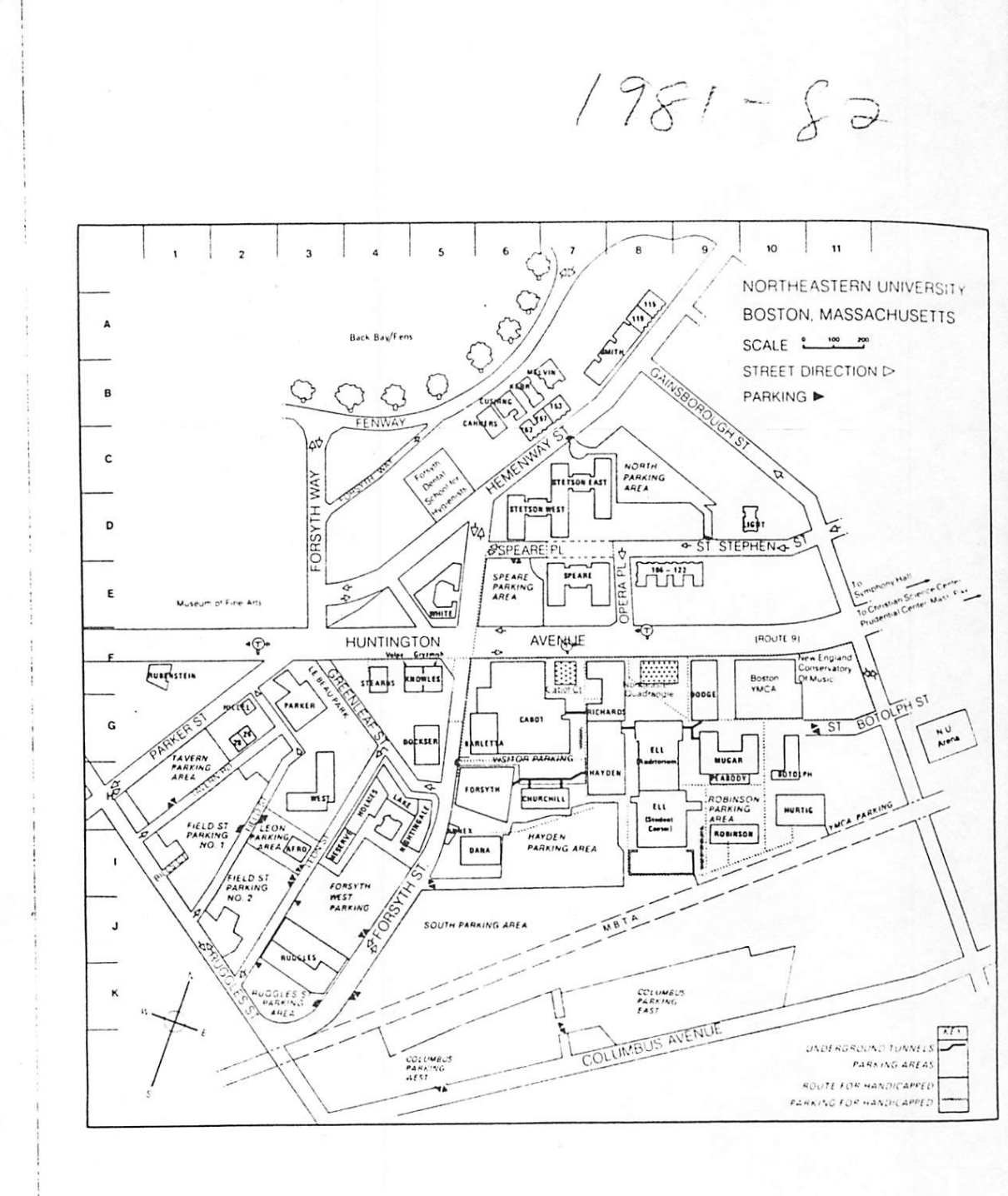

Because many students and faculty members commuted to campus in 1987, the recommendations to bolster the campus’ image included reorganizing the parking structures to maintain a pedestrian-focused campus while also accounting for enough parking space.

In its recommendations section, the plan details the “establishment of an east-west oriented mall anchored at the new Resource center site which will extend to the west across Forsyth Street to Parker Street.” The implementation of green space would allow Northeastern to create a “campus feel,” the planners wrote. The open space recommended in the plan is now Centennial Common.

Today, Northeastern’s website reads that the “Boston campus offers a traditional American college experience in the heart of this thriving east coast city.” Other nearby schools, such as Boston University and Emerson College, are more urban and don’t have the same centralized campus design.

The plan acknowledges that Northeastern is located within various Boston neighborhoods without a distinct separation and suggests that more distinct “entry pathways” should be created to enhance campus identity.

When addressing the surrounding areas, the planners wrote that “external influences will contain both positive and negative characteristics. Thus, the Campus Master Plan must not ignore the land use dynamics external to the University but must respond by embracing positive change and by protecting the campus from potential negative influences.”

Planners did not elaborate on what “potential negative influences” they were referring to.

A “competitive edge” and increasing enrollment

In the years leading up to 1987, Northeastern faced a stark decline in enrollment. In 1983, there were 17,235 full-time undergraduate students. In 1985, this number dropped to 16,837, according to page six of an archived 1986 Inventory Report.

The Master Plan addresses this enrollment drop, stating the university “should focus on improvements to the campus, educational programs and student services that enhance its competitive position.”

Parking was a major concern of the university in the 1980s and 1990s because of the commuting students. In contrast to the most recent plan, where Northeastern outlines intentions to tear down the Gainsborough Garage, this 1987 plan discussed implementing large parking lots and new garages.

Designated parking lots were located where Snell Library, Centennial Common and parts of West Village now stand. Parking garages on Columbus Avenue and Gainsborough Street replaced these lots.

The plan reflects that only about 4,000 students lived in university housing at the time.

“Upperclass students represent over 1,600 of total students housed, while freshmen occupy almost 2,300 of the available beds,” page four of the Inventory Report reads. “Also housed by the University are 111 graduate students.”

According to the 1985 total enrollment figure, approximately 30,000 Northeastern students were considered commuters.

Northeastern officials projected that overall enrollment would decline in the coming decades due to the “declining college age population nationwide,” according to the introductory pages of the Master Plan. Because of this, the university expressed a desire to improve the campus, academics and student resources to make the university more attractive to potential students.

“The modest rise in full-time undergraduate enrollment expected near the end of this century is reflective of the ability of Northeastern University to identify and implement strategies which address enrollment issues,” planners wrote.

This section of the plan also stated that the university must expand its student resources, including building a student resource center and additional facilities for the College of Engineering and D’Amore-McKim School of Business. University officials wrote that increasing student housing should be a priority in its first Master Plan.

“As a partial demonstration of potential demand, over 75% of the freshman applicants indicated the desire for on-campus housing,” page 15 of the report reads.

Planners pondered increasing classroom and lecture hall sizes to support growing future enrollment, with the Inventory Report stating a need for 62 additional classrooms.

“The existing lack of a sufficient supply of large classrooms facilities constrains the University from increasing enrollments in classes where enrollment demand outstrips the room capacities,” page 11 of the 1986 Inventory Report states.

The plan also outlines the addition of 90,000 assignable square feet of research space dedicated to various research topics including electromagnetics, software engineering and biotechnology. Establishing more research space helped Northeastern achieve its position as an R1 institution for research, meaning it is classified as one of fewer than 150 universities with the highest research activity, an accolade first awarded in 2015.

Northeastern’s campus today

The 1987 Master Plan significantly shaped how Northeastern’s campus looks now.

Buildings like Snell Library, the Interdisciplinary Science and Engineering Complex and EXP, which are new engineering and science buildings, Curry Student Center, Marino Recreation Center and outdoor areas like Centennial Common are direct results of the vision that Curry and the Northeastern administration had in the 1980s and early 1990s.

When this plan was created, Curry was serving as executive vice president of the university alongside Kenneth Ryder, the president at the time. Curry became president in 1989 but worked on the plan prior to his presidency and is credited with carrying out the plan.

In a letter addressed to Curry in 1985, Perry Chapman, principal-in-charge of Sasaki Associates, expressed his eagerness to continue working with him.

“We look forward to continuing our involvement with development of the master plan for Northeastern University and are genuinely excited at the opportunity to apply our multi-disciplinary approach to the project,” Chapman wrote. Northeastern continues to work with the company today.

During Curry’s presidency and the implementation of the Master Plan, 716 Columbus Ave., the former headquarters of the Northeastern University Police Department, was completed, effectively expanding the university into Roxbury. Snell Library opened in 1990, Marino Recreation Center opened in 1995, Shillman Hall was constructed in 1995 and Northeastern began constructing a new building in 2007, which would later become International Village when it opened in 2009.

“Jack Curry was a giant who laid a foundation for decades of success at Northeastern following his presidency,” current Northeastern President Joseph E. Aoun told Northeastern Global News last year.