By Isaac Feldberg, news correspondent

The word “biopic” far too often refers to those stodgy, overwrought yawn-fests that most moviegoers avoid like the plague, but not all of them fall into that trap. In “The Theory of Everything,” director James Marsh demonstrates that the best biopics are those that avoid sanctifying their subjects, and instead embrace the grimy, sweaty, passionate truths too often left out by the history books.

At first blush, Marsh’s subject, theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking (Eddie Redmayne) might seem incompatible with that approach, but the magic of Anthony McCarten’s terrific, surprisingly witty script is in how it turns back the clock to erase the common image of Hawking as a wheelchair-bound, robot-voiced intellectual.

Indeed, the Hawking we first meet, circa 1963 (a time gorgeously recreated by Marsh and talented cinematographer Benoît Delhomme), will come as a shock to some. As he races around the Cambridge campus on his bike, there’s a dazzling exuberance in Hawking’s manner. His smile is broad and unceasing, his eyes bright and thoughtful. As portrayed by Redmayne in an unqualified marvel of a performance, Hawking is brilliantly alive, his lanky frame almost bursting at the seams with an unquenchable thirst for discovery.

Hawking is also a bit eccentric, his head firmly in the clouds as he solves problems that baffle his classmates. That is, until he meets Jane Wilde (Felicity Jones), a beautiful peer who shares his zest for uncovering life’s great mysteries, even as she disagrees with him about God and the arts. The two quickly fall for one another with the same all-consuming ardor that they bring to their respective pursuits of knowledge. To watch their romance is to witness two individuals become intertwined.

Marsh captures the totality of their love, but doesn’t shy away from its challenges, particularly once Hawking is struck down by motor neuron disorder, a debilitating condition that doctors tell him will devastate his body and kill him within two years. Though Hawking is gutted by the diagnosis, Wilde’s support becomes a driving force, propelling him forward into a 25-year marriage that results in three children and catapults him into the forefront of theoretical physics, where his ideas galvanize the academic community.

It’s not a storybook romance for the pair, a point “The Theory of Everything” takes great care to make. Hawking’s ambition and illness take a heavy toll on Wilde. The pair’s ultimate separation, partly motivated by Wilde’s blossoming attraction to Hawking’s caretaker (Charlie Cox), is as raw and emotional as their whirlwind first years together. As the film charts the couple’s highs and lows, Redmayne and Jones deliver two of the most outstanding performances of the year, both inhabiting their roles and building off of one another to convey the complexity of their relationship.

The physical transformation Redmayne depicts, in a stunning feat of acting, will make him a shoo-in for Oscar attention. He shouldn’t be the only one. Jones summons a quiet strength and fire that’s absolutely mesmerizing to watch. The film is a showcase and triumph for them both.

It’s also a landmark achievement for Marsh, who lays bare a near-Godly cultural icon to reveal the inspiring and imperfect man beneath. Few films would dare to show this much aching humanity and undisguised passion for their subjects, but the emotion with which Marsh and McCarten infuse each scene is plainly invigorating. You’ll smile, you’ll laugh and you may cry – but with such powerful subject matter, any film that didn’t conjure such a range of emotions would have been a failure.

Time is at the center of “The Theory of Everything.” It’s easy to wish that Marsh had spent more of it to chart Hawking and Wilde’s messy divorce and Hawking’s subsequent relationship with doting nurse Elaine Mason (Maxine Peake), but the film is less concerned with the pair’s later years than with their deeply moving, unconventional romance. How “The Theory of Everything” details that spellbinding love story is both luminous and illuminating.

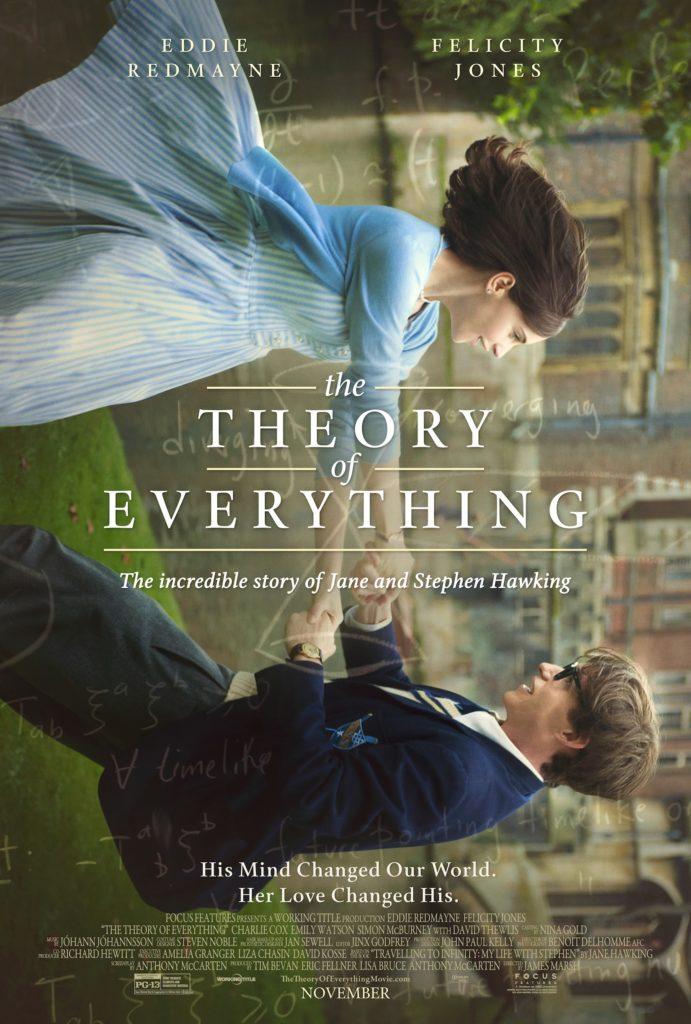

Photo courtesy Focus Features Press