Women who lived in Shakespeare’s time were wooed by men with words like “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” Literature was sacred and revered; writers were gods, reaching all those capable of reading the letters on a page into beautiful words that people would discuss for weeks, even months.

Today, a woman is more likely to read “u r hot,” or, if she’s lucky, “u r gorgeous.” Very few people are well-spoken and eloquence is as scarce as a handwritten letter. We are knee-deep in the technological age, and people want information as quickly as possible.

An entire page of a newspaper is consolidated into a tweet, an entire love letter into a text message, both tapped out with hasty thumbs for instant gratification.

Standards have changed as the years passed, and not for the better. Sure, there are benefits to this hurried lifestyle, this fast-paced reality, but how can a person claim intelligence when their knowledge is made up of thousands of snippets, each written in 140 characters or less, rather than extensive ideas?

A tweet from The Boston Globe on Wednesday reads, “Sen. Edward Markey says #FCC is ‘finally getting it right’ with net neutrality proposal.” There is no room for ignorance – one must know who Markey is, what FCC means and what the net neutrality proposal refers to. And in order to really understand it, one has to know how the FCC has been getting it wrong all this time. That’s asking a lot from a casual reader who is scrolling quickly down a Twitter feed with the absent-minded flick of a thumb.

Granted, there is a link to a full story, but the “full” story isn’t even 500 words. This is not an attack on The Globe by any means, but rather an observation of the state of our information: adapt or die.

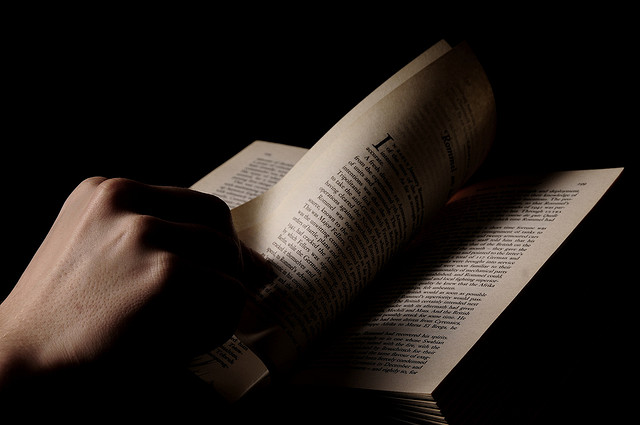

Not only is news consumed differently, but books have become a luxury rather than a necessity. Bookstores are going out of business, writers are struggling for pay and people can have their own manuscripts published on sites like Amazon for a price. Gone are the days when a handful of big-name companies ruled the publishing world. Now these big-name companies are struggling to keep up with the times and rueing the digital age that is cheating authors and publishers out of profits.

People used to write for pleasure and others could derive their own forms of pleasure from that. It seems that the pleasure is gone from the publishing world – both in news and in books. Everything is a race; everything is a competition – authors and journalists rushing to meet deadlines, resulting in slip-ups and an innumerable amount of I-could-have-done-betters.

This is a world rife with information, links and tweets and posts at our fingertips at every moment, the trending topics ever changing. But with its ever-changing nature comes a lack of sincerity, a lack of emotional connection. Writers aren’t forced to research topics as much as they were in the past; journalists don’t have to dig as deep as they used to because there are hundreds, thousands of online databases overflowing with information. The reporter doesn’t make that emotional connection with the story, and therefore neither does the reader. Cancer patients and victims of shootings become statistics – one of just thousands of others – another shape lost in a sea of corpses.

Readers, consumers and people need to take a moment, a day, to disconnect, to pick up a newspaper and read an entire story about something, to soak up all the information presented. Go to a bookstore, pick out a book, buy it and read it – not because you have to, but because you want to. Find a passage you really like and re-read it, highlight it, re-read it again, dog-ear the page to look back on later, read it to someone you care about.

The artistry in our information is getting lost in the uproar of daily life. Gone are the days of sonnets and lengthy reports that draw tears from the eyes of those whose fingers are stained black with the ink of a newspaper. So, every once in awhile, settle for paper cuts instead of mouse clicks and pages turned rather than refreshed.

Photo courtesy Kamil Prembinski, Creative Commons