By Pamela Stravitz, news correspondent

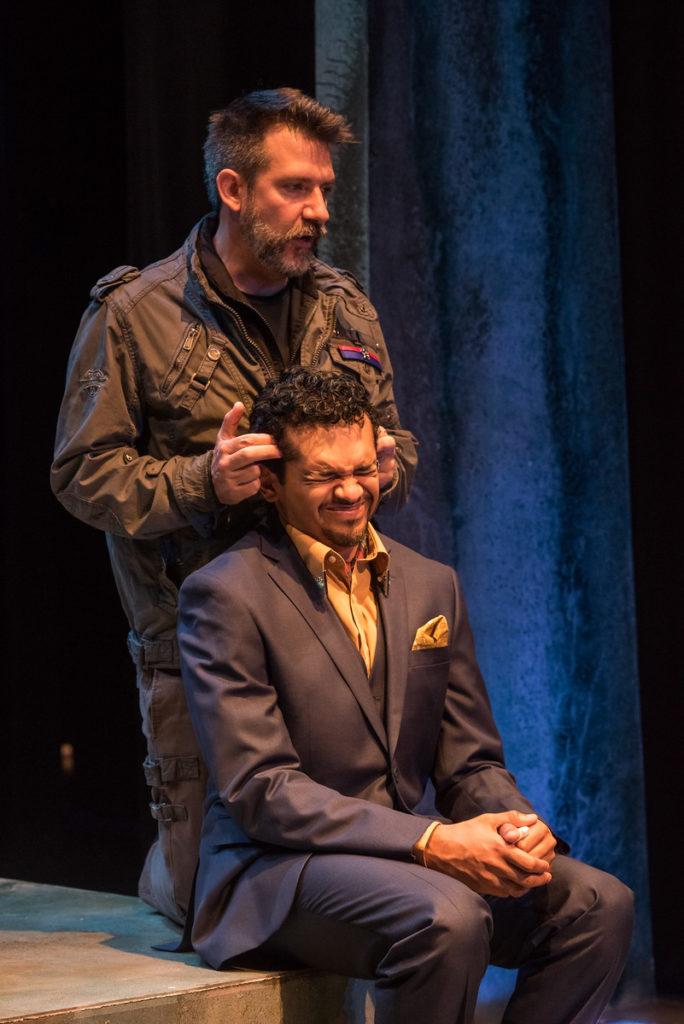

The Suffolk University Modern Theatre was packed as the audience quieted, lights dimmed and Roderigo stepped out from the aisle in a three-piece suit, followed by Iago, fully dressed in 21st-Century army fatigue.

The Actors’ Shakespeare Project’s production of “Othello” premiered Friday, Sept. 23 and will run until Oct. 25 under director Bridget O’Leary, who is also a theatre lecturer at Northeastern University. For those who know Shakespeare’s “Othello” well, the new millenium aesthetic may come as a surprise, given the play is traditionally set in the 17th Century.

For her first professional Shakespearean show, O’Leary wanted to make the production seem accessible to a modern audience.

“It was important to me that when people watched, it debunked the stereotypes of who these iconic characters were and made them real, like you were seeing something for the first time,” O’Leary said.

Othello (Johnnie McQuarley) is the protagonist and a Moorish military general. Iago (John Kuntz) stands as Othello’s devious right-hand man, and Roderigo (Bari Robinson) is Iago’s gullible henchman. Iago’s honorable position in the army is contradicted by his manipulation of his wife, Emilia (Jennie Israel) and his betrayal of Othello and Desdemona (Josephine Elwood), Othello’s bride. As Iago falsely convinces Othello of Desdemona’s disloyalty, he causes a trail of chaos, murdering innocent people in the process. While the result of their actions are drastic, the characters convey feelings that are synonymous with those people experience today.

The space of the theater brought these characters to life. The close-up orchestral seating of the audience allowed people to interact with the characters and become enveloped.

“As a design team, we talked about wanting it to feel like it was everywhere and nowhere,” O’Leary said. “When we talked about costumes, we asked, ‘Who were these militaries? Are they the marines? Are they naval? Are they US ambassadors?’”

One of these military men, McQuarley, has been in other Shakespearean tragedies but said “Othello” offered something more relevant than his past works.

“In rehearsal, [McQuarley] spoke about this internal racism that spurs on Othello’s jealousy by his own acknowledgment of his place in the world,” O’Leary said. “He was less sure of Desdemona’s love for him or other people’s faith in him as a leader and a man. It’s what makes Iago so successful.”

McQuarley also understands the divide between Othello and those he lives and works with.

“[Othello] can’t go back to where he’s from,” McQuarley said. “Other roles I’ve played have had a very solid genesis that they can turn to. Othello seems to be starting from the middle, trying to discover himself in a new way in a new world.”

Some parts of the plot, however, were more difficult to adapt to a contemporary setting. One of the most obvious contemporary changes O’Leary made was the switch from casting a Brabantio, Desdemona’s father, to Brabantia. No longer is the character an overbearing father, unwilling to give away his property; as a woman, Brabantia is still stubborn but understands Desdemona’s desire to choose.

Costume director Tyler Kinney created humor with his wardrobes. Laughter bounced off the confined walls of the theater as Cassio popped his collar or Emilia unexpectedly pulled a handkerchief from a keyhole on her blouse. Characters in blue jeans, crop tops and military camouflage helped solidify this idea of accessibility.

However, O’Leary understands that the idea of jealousy and manipulation were still the most modern aspects of the show.

“It’s upsetting to think that a play like ‘Othello’ could still resonate in a way that we feel connected to,” O’Leary said.

Photo courtesy Joanne Barrett, Stratton McCrady Photography