In last year’s State of the City address, Mayor Martin J. Walsh stood up in front of 2,500 Bostonians and vowed to champion improvements to the city’s schools.

“I am not satisfied,” Walsh said. “The Boston Public Schools (BPS) can do much better for our kids. We have to do better. We will do better.”

Twelve months later, Walsh and the city have ostensibly taken steps toward fulfilling that promise. After an in-depth search, the mayor tapped Tommy Chang to take over as superintendent. Since then, the school system has hired 24 new principals; the school day for K–8 students has been extended by 40 minutes a day, a change hailed by the Boston Teachers Union; and access to pre-kindergarten programs grew citywide.

However, beyond these accomplishments – which Walsh was eager to highlight in the 2016 version of his speech, delivered Tuesday night – the mayor’s actions on education should trouble parents, teachers, students and community members in Boston.

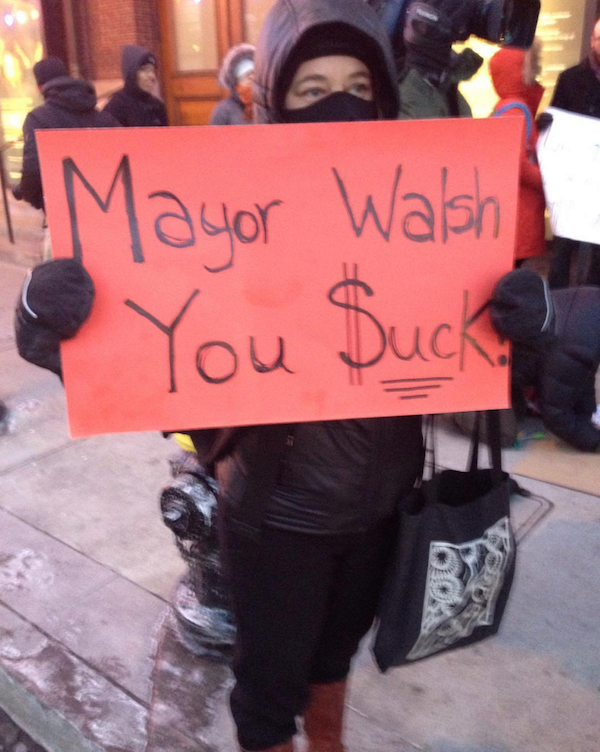

Earlier this week, Chang announced Boston schools face a $50 million shortfall. Before the mayor’s speech, protesters gathered outside Symphony Hall and called for Walsh to respond to pains underfunded schools are feeling. One veteran teacher expressed dismay that his students with special needs were being marginalized. Carlos Rojas Alvarez, a 2012 BPS graduate, said he was concerned that his ninth-grade brother hadn’t seen his school’s librarian in three weeks. Dozens of protesters told The News they feel abandoned by the kid from Dorchester nearly all of them had once voted for.

Walsh responded with unabashed dismissal, suggesting the shortfall is an apparently unimportant $10 million. In his address, he committed $13.5 million more to BPS next year – even as he admitted costs have gone up by at least $20 million. This does not sound to us like much of a solution. Indeed, Walsh all but admitted as much: his supposed commitment to public schools is wavering in favor of publicly funded, privately operated charter schools with cozy corporate ties.

We at The News do not believe charter schools are an acceptable path forward for Boston schools. Their supporters often point to a 2013 Stanford study that says students at the city’s six highest-performing charters perform better on math and science tests than peers at public schools. But those results are misleading.

Charter schools drain much-needed money from public schools, creating a separate but unequal system. The more money they siphon, the bigger the gap gets. As hamstrung schools inevitably decline, students and families leave. In turn, those sites are shuttered – and, too often, handed over to charter operators.

Such schools often set themselves up to succeed by taking on students more prone to academic achievement and protecting those numbers at great lengths. That same Stanford study noted 30 percent of BPS students as a whole are English-language learners (ELL), a need which creates special challenges for teachers, especially in regard to raising test scores. The percentage of ELL students in Boston’s charter schools? Just eight. Surely, a system that largely excludes them cannot be in their best interests. Charters also struggle to serve students with disabilities.

Perhaps an even bigger problem is the hyper-disciplinary culture of charters, which can verge on militancy. In the 2012-13 school year, Boston’s traditional public schools suspended about six of every 100 students. Boston Preparatory Academy and Boston Excel Academy II both used exclusionary discipline on more than 20 of every 100 students; City on a Hill Charter’s rate topped 40; and at Roxbury Preparatory Charter, an unbelievable 60 of every 100 students were suspended at some point.

Paying outside entities to narrowly focus on test scores and affording them free rein to repeatedly suspend, kick out and ignore students isn’t innovation. It’s failure. Instead of expanding funding for charter schools, the mayor must show Bostonians his commitment to their children is more than just lip service.

Last week, the city gifted $25 million to General Electric – whose annual revenues reside in the billions – in exchange for the company’s move to Boston. Hidden in the contract was nearly $100 million more to reopen the Old Northern Avenue Bridge, closed two years ago in response to safety concerns. Walsh justified those expenses as an “investment” in the city’s economic future. Surely he can find $50 million more to invest in the futures of the 56,000 kids in need of strong public education.

Photo by Sam Haas