By Connie E, news correspondent

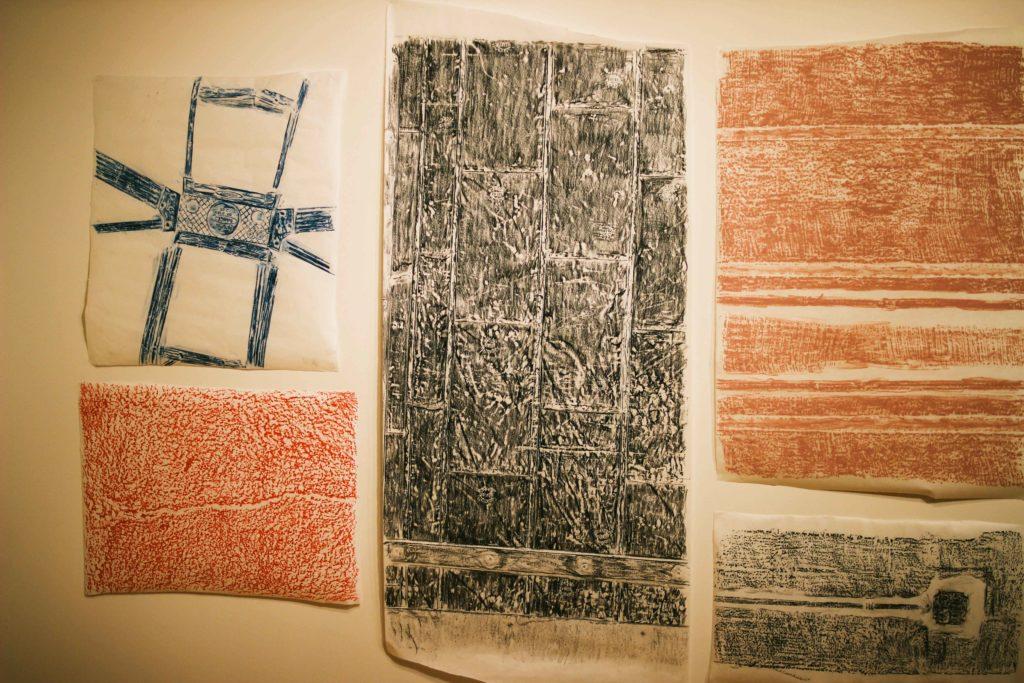

She slathered the walls and floors of buildings with ink and then pressed paper against them, creating representations of architectural surfaces.

“These rubbings came out of the idea of how one captures a space without creating a digital image, but by perhaps using a very old-fashioned technology – such as pencil and paper – to create a document of the space,” artist Jennifer Bornstein said.

“On Exactitude in Science,” an exhibit presented by the School of the Museum of Fine Arts (SMFA) and curated by Dina Deitsch, invites the public to rethink our relationship with tactile surfaces.

The title of the exhibition is borrowed from Jorge Luis Borges’ short parable of the same name, in which cartographers create a map of an empire so precise that it matches the empire’s own scale. The map created is no longer a navigation device, but a realistic imitation.

“In the digital age, images are no longer physically tethered directly to the real, no longer imprints of light and shadow, but rather hinged to pixels and code,” Deitsch remarks in her written introduction of the exhibition.

In her artwork, Jennifer Bornstein captures the interior of the former building of the Dia Art Foundation in New York, where she has worked and feels affection for, before the building was purchased for commercial renovation. The wax rubbings record not just the loss of a particular art space, but also the passing of the direct film photograph.

“Coming from a background of photography, I was trained to capture the world through a lens,” Bornstein said. “Along the line of 25 years since I first started studying photography and film, I started to see opportunities to leave this behind and to think of other ways to create a representation of the world which has nothing to do with the camera.”

In 2003, Bornstein started to think about the tension between what she sees around her in “the world of JPEGs and YouTube,” and what she can create herself.

“The ease of making a photo of something on our digital devices has become so omnipresent in our culture that I felt like I was surrounded by a hurricane of images that were very easily produced and were unfiltered,” she said.

In her work “The Map of Exactitude,” artist Elizabeth McAlpine used a pinhole camera inside a wooden box, lined the newly cast cameras with photo-paper and capture the spaces from which they took shape. Though viewers might find the work conveys minimal information, curator Deitsch interprets it as a way to see space as a process, as an ever-unfolding action of light and touch.

Manna, an American-born Palestinian artist, brings a series of post-minimalist sculpture made of the so-called “Jerusalem stone” to evoke the volatile relationships between the Palestinian-dominant East Jerusalem and the Israeli-dominant West. Her “Unlicensed Porch” series recreates the limestone-clad stoops from the Silwan neighborhood, an exclusively Palestinian area.

Çavuşoğlu, a Turkish artist, recalled an ancient fortunetelling practice of reading architecture in her work “Words Dash Against the Façade.” Viewers can use earphones to listen to how the buildings ‘speak’ through the artist’s narration.

“As a curator, my feeling is how can you bring art that matters together. It’s a very simple equation with endless complications and creation,” Deitsch said.

To her, all four artists all similarly address the act of representation through fragmentary devices. Their creations are grounded in experience, favoring touch over vision, and the detailed fragment over the completed image.

“The exhibition definitely leaves me thinking about the connections between the objects, materials, and time-based artworks that render the history behind those architectures that they are based on,” Ashley Chacon, a freshman at the SMFA, said.

Photo by Nola Chen