End-of-life chatbot aims to comfort terminally ill patients

October 20, 2017

Dying carries more burdens than the just the emotional baggage people tend to associate it with. In addition to coming to terms with their deaths, the terminally ill must make important legal decisions, involving issues such as health care and what to do with their property. To facilitate this process, a Northeastern professor and his team of students and medical personnel have created a chatbot aimed at helping terminally ill patients older than 55-years-old with six to 12 months left in their lives.

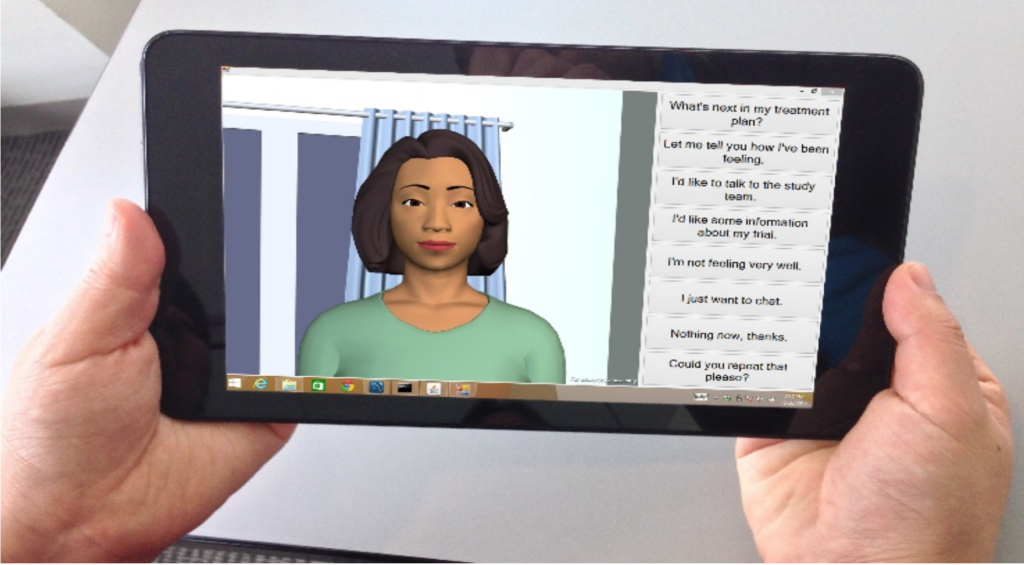

The chatbot, a program run on a tablet, is a machine known as a relational agent.

“It’s an artifact designed to pull on our emotional and relational strings to draw us into a trusting relationship with them,” said Timothy Bickmore, associate dean for research at the College of Computer and Information Sciences and the professor leading the chatbot project.

While other chatbots, like Mitsuku and Rose, learn from the interactions they have with their users, the end-of-life chatbot sticks to a predefined script. This prevents it from giving potentially harmful or false information to users, as learning bots are prone to do. It also allows the agent to focus on three specific topics with its user: writing a last will and testament, declaring a health care proxy and assisting with funeral preparations.

Also separating it from other devices with similar functions is the bot’s ability to discuss spirituality with its users. The bot currently has dialogue scripts for Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism, atheism, spiritual humanism and secular humanism.

“I think if you can use automation to accomplish something like that to truly help someone in those circumstances, then it’s only a good thing to invest in,” said Artie Ghosh, a first-year communication studies and media and screen studies major. “Besides that, I’m a believer in spiritual practices and I think that if you can combine technology with spirituality and use it to aid someone in that way, in their terrible circumstances, then I think it’s definitely a very beneficial thing.”

If that sounds like a lot of information, it is. Bickmore said he and his team met with various health professionals and religious leaders over the course of a year and a half to put together the agent’s responses. The team used template-based text generation, where information is placed into pre-built conversational structures, to turn these meetings into conversational dialogue.

“They’re essentially hand-written, but they can be parameterized and combined in different ways based on time of day and the patient’s needs and their spiritual background and where they’re at in their health trajectory,” Bickmore said.

To better connect with patients, the chatbot renders a cartoon human known as a virtual agent on one side of the tablet screen and a list of responses on the other. The goal is to convey nonverbal communication, including hand gestures, posture shifts, head nods and facial displays. The agent can also bring up paperwork and other visual aids.

The bot’s spiritual affinity, which is only one of six modules that make up the project, is a heavy focus of the team’s research. Dina Utami, a Ph.D. student was in charge of the spiritual module and implemented the module’s script.

“One thing we learned from the study is the need for individual tailoring and giving users options to stop or continue talking about spiritual topics because some of them want deeper conversation and others think more would be too intrusive,” Utami said.

The device’s new clinical trial tested the bot with two versions: a control group with no agent and a treatment group with a spiritual agent. As a result, the spiritual module has been upgraded to gain a better understanding of a patient’s spiritual background, including their daily practice and afterlife belief. The daily chat has also been updated to converse with the patient on topics such as prayer, religious holidays and thankfulness, Utami said. These chats are intended to assist in building a long-term relationship with the patient.

Another version of the spiritual module, used in a test to determine whether older patients prefer talking about spirituality to a virtual agent rendered on a tablet screen or with a full-on robot, the device is given its own spiritual background and belief, aligned to the that of the patient’s. The agent’s autonomy in this trial is furthered by its ability to disagree with the patient, helping it seem less like a series of responses and more like a human conversational partner, Utami said.

Though it to seeks to mimic them for the sake of conversation, the agent isn’t designed to replace human caregivers, but rather to assist them in caring for their patients. If the patient reports problems that may require a medical intervention, the nurse is notified. The bot monitors patient’s health by occasionally asking them how they’re doing amidst normal conversation. This information is also sent to the nurse. The patient’s family caregivers will not get the medical information, but they will get general information about some of their symptoms and quality of life.

While significant progress is being made in testing the chatbot’s various modules and expanding its capabilities, there is no plan to pursue a commercial release. The purpose of the project is to learn what works and how it helps patients. To Utami, it’s also a valuable source of experience.

“[Jacob] Nielsen, a prominent user-experience expert, said that, ‘One of usability’s most hard-earned lessons is that you are not the user,’” she said. “This was a particularly good project to practice that. I learned a lot about death preparation and different spiritual and religious tradition, beliefs and practices in the process.”