By Alyssa Lukpat, news staff

John D. O’Bryant, a trailblazing African-American politician and educator in Boston, was famous for his neighborhood cookouts.

He never hosted them just to make food for his family and friends. Sure, he got to show off the cooking skills he mastered in the Korean War. And yes, he gathered his five children and wife together for some quality time. But the reason O’Bryant hosted cookouts was to hear the concerns of the local community.

Richard O’Bryant, John’s son and the current director of the John D. O’Bryant African-American Institute at Northeastern, remembers how his father would invite everyone in the neighborhood to his gatherings.

“All the folks who came thought it was just a family thing, but in hindsight it was probably political and, you know, in politics, keeping constituents happy,” Richard O’Bryant said. “He never said that, but he was always the one who would work the grill and was the center of it all.”

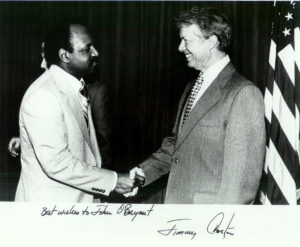

When John D. O’Bryant died on July 3, 1992, his prolific career had touched everyone from his students to former President Jimmy Carter, Senator Edward M. Kennedy and activists Coretta Scott King and Fannie Lou Hamer. O’Bryant was a pioneer: He was the first African-American guidance counselor in Boston and the first African-American vice president of Northeastern.

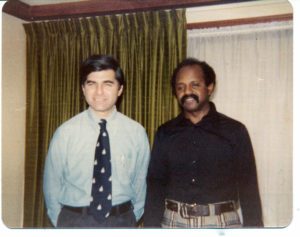

Michael Dukakis, the former governor of Massachusetts and 1988 Democratic presidential nominee, formed a close friendship with O’Bryant early in their careers. Dukakis watched O’Bryant blossom into a trailblazer for the African-American community.

“John was one of the young leaders that came out of the black community and became an extremely effective leader,” said Dukakis, who is currently a political science professor at Northeastern.“Then, of course, he went on to do some great things at Northeastern and just stood out as a bright, young, progressive and very gutsy leader at a time when race relations in the community were terrible.”

O’Bryant was educated in the Boston Public Schools and attended Boston University, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in education in 1952. He was a cook in the U.S. Army from 1952-54 during the Korean War before he returned to his alma mater to earn a master’s degree in health education in 1955.

After finishing graduate school, O’Bryant taught in the Boston Public Schools, where he was a mentor to many. Richard O’Bryant described an instance when John encouraged one of his students to join the football team and stay away from a gang; the student became a successful college athlete and credits John D. O’Bryant with saving his life, Richard O’Bryant said.

John’s wife Cicily O’Bryant recalls how he was a father figure to many of his students.

“He was just a few years [older] than the people in high school and he got attached to them,” she said while in her home. “He never looked at himself as being special; he thought that’s what you were supposed to do.”

Richard O’Bryant said his father could not be a head coach for basketball, his favorite sport, because of racist attitudes in the 1960s. He was an assistant basketball and football coach for the Boston Public Schools and later became a guidance counselor, Richard O’Bryant said. In 1969, John D. O’Bryant left the public school system and ran a health vocational training program at the Dimock Community Health Center in Roxbury.

His first introduction to politics was running Massachusetts politician Mel King’s unsuccessful 1959 and 1961 campaigns for the Boston School Committee, or BSC, which has been the governing body of the Boston Public Schools since 1789. King became a lifelong mentor to O’Bryant and encouraged him to run for a spot on the BSC himself.

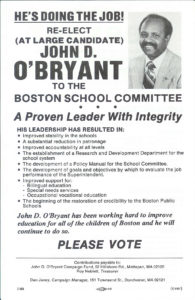

Although O’Bryant lost the 1975 election, he won in 1977 to become the first African-American person on the committee in 76 years. He served on the BSC during the desegregation of Boston Public Schools and was its president until 1990. He briefly considered running for mayor in the last years of his life, Richard O’Bryant said.

Richard O’Bryant remembers how difficult it was for his father to be an African-American man in politics during desegregation in Boston.

“It can’t be overemphasized how challenging his time in running for office was given the environment and the climate. He was a recipient of death threats,” he said. “He was really adamant about not losing focus on trying to help kids in the school system, despite how difficult the environment was. He seemed to look past it all with great courage and great fortitude.”

Jean McGuire, the former director of the Metropolitan Council for Educational Opportunity, said O’Bryant convinced her to run for the BSC. She fondly remembers sitting in committee meetings with him until 2 a.m.

“We were the only two at-large members who were black, but it didn’t bother us. Most of the kids in the system were children of color,” McGuire said. “John and I, our real goal was to make the Boston school system responsive to a changing world.”

After the BSC acquired more representation from local districts, Dukakis remembers how O’Bryant took charge of the committee.

“John himself was a leader in that new school committee and made no bones about the fact that he wanted and expected change and was going to work for it,” Dukakis said.

In addition to the BSC, O’Bryant sat on numerous committees to promote education, including the Black Educators’ Alliance of Massachusetts, the Council of Urban School Boards of Education and the Citywide Coordinating Council, which helped carry out the desegregation of Boston schools in the 1970s and 80s.

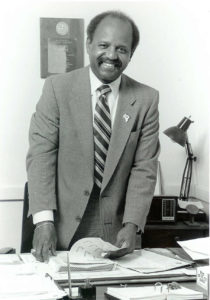

O’Bryant was appointed as the associate dean of administration at Northeastern in 1978, and became the first African-American vice president at Northeastern when he was promoted to vice president of student affairs one year later. O’Bryant encouraged young African-Americans in the community to pursue higher education.

Richard Harris, the director of the NU Program in Multicultural Engineering and assistant dean for academic scholarship, mentoring and outreach in the Northeastern College of Engineering, was an undergraduate at Northeastern while O’Bryant was the vice president of student affairs. Harris said O’Bryant frequently met with students to help their campaign to encourage the university to divest from South Africa in protest of apartheid.

“He meant to many of us the example of leadership that didn’t look for personal aggrandizement, but more so focused on what would be the greatest impact for society at large,” he said. “He was very approachable, accessible, affable and had no airs about himself.”

In 1993, one year after his death, Northeastern renamed its African-American Institute as the John D. O’Bryant African-American Institute. He is also the namesake of think tanks, scholarship funds, high schools and youth centers.

Richard O’Bryant said he was amazed at the compassion his father devoted to every job he took to create opportunities for people of color in Boston. But even though John D. O’Bryant was busy, he always made time to attend his sons’ sports games.

“He somehow always found a way to come to our games. I don’t know how he was able to do it, but he seemed to always be there,” he said. “I just have fond memories that he was always at my games and swim meets.”

O’Bryant married his wife Cicily in the 1960s and had five children: John, James, Richard, Paul and Bruce. He had one son, Norman, from his marriage to his first wife, Cynthia.

Richard O’Bryant said anyone who knew O’Bryant remembers how much he adored basketball and the Boston Celtics. He valued his Christian faith and loved fitness, swimming, music, the singer Marvin Gaye and eating out at restaurants.

Dukakis said Boston would be a different city today if O’Bryant hadn’t worked tirelessly to create opportunities for young people and people of color.

“He was always a guy with optimism and confidence and a real belief that we could make things better,” Dukakis said. “People like John really started us on a much better road. We still have work to do, needless to say, but Boston is a much better city because of people like John.”