By Patrick Burgard, interim managing editor

Scholars, policymakers and correctional officers from across Massachusetts convened at Northeastern on March 23 to brainstorm solutions to end mass incarceration in the state and throughout the country.

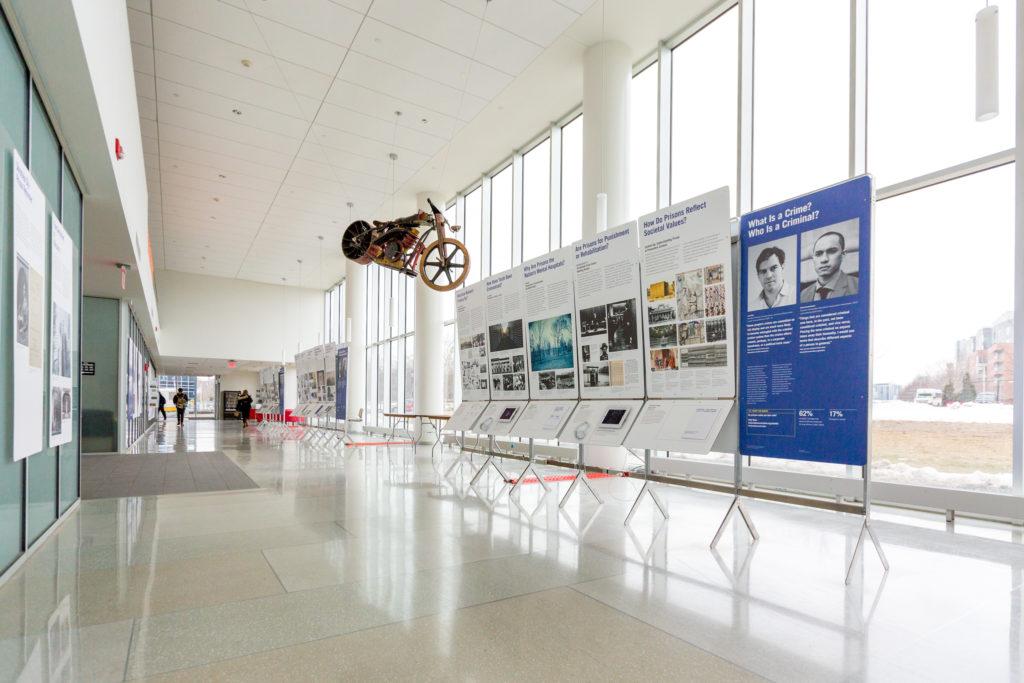

The event, titled “MASS Incarceration: A Symposium on the Past, Present and Future of Incarceration in Massachusetts,” took place in the Cabral Center at the John D. O’Bryant African-American Institute and was hosted by Northeastern’s Program in Public History and the School of Criminology and Criminal Justice.

It was part of a larger project called “States of Incarceration,” a travelling exhibition that seeks to understand how the United States became the world’s leading incarcerator and thinks up solutions.

Carlos Monteiro, an assistant professor of sociology at Suffolk University who co-authored a book chapter on mass incarceration solutions, said the dramatic rise in America’s prison population is due to a collection of racist, classist laws enacted in the last half century, commonly referred to as “the new Jim Crow.”

Some of his proposals from the chapter are ending imprisonment for drug crimes, repealing mandatory minimums, reducing sentence lengths across the board and — most importantly — reserving prison for people who are “truly dangerous,” as is done in much of Europe.

“There are 2.2 million people in our nation’s prisons and jails,” Monteiro said. “That represents an increase of about 500 percent over the past 40 years. I want to emphasize that it has a lot to do with changes in policy, not necessarily changes in crime.”

These federal, state and local laws include mandatory sentences for certain offenses — known as mandatory minimums — and additional punishments for those who have already been convicted of a crime. People of color, people in poverty and people without access to education are disproportionately impacted by these statutes.

Monteiro said that some progress has been made as several states have implemented reforms like justice reinvestment, which aims to lower criminal justice spending and invest the savings into the communities most impacted by incarceration. However, he said that while such revisions are beginning to mitigate the trend of mass incarceration, it will take too long before their effects fully take shape.

“These approaches might work in the long term, but what we say [in our chapter] is that they will take years, if not decades, to actually create meaningful changes,” Monteiro said.

Monteiro said the United States needs to enact bolder policies that will protect those who currently face the threat of incarceration.

“In the 1970s, it was argued that punishments should be scaled to match crime severity… But back then, they were scaling in terms of years, not decades,” Monteiro said. “So, if we were to stop incarcerating low-level property offenders, low-level drug offenders — if we did that all together — sentences of five to 10 years for crimes of violence would eventually be seen as long again.”

This point by Monteiro is especially pertinent in Massachusetts, where the prison population continues to age due to the Commonwealth’s high proportion of “lifers,” who have been sentenced to a life term in prison.

In the state’s prison system, one in five inmates is a lifer, said Rhiana Kohl, director of strategic planning and research at the Massachusetts Department of Corrections.

At the Department of Corrections, Kohl tracks prison demographics and advises the department on the needs of the current population.

She said that within the incarceration research community, there is a lot of emphasis placed on recidivism — the likelihood of criminal to commit another incarcerable offense after being released. This is a problem, she said, because it doesn’t take into account the struggle of reacclimating to life outside the prison gates.

For example, Kohl said that long prison sentences put the modern prisoner at an extreme disadvantage because of the pace at which technology advances in the 21st century.

“One of the things we discovered is that when you’re in prison too long and you’re trying to use some of the technology when you get out, you can’t function,” she said. “You can’t even get a CharlieCard. Job applications are online.”

Suffolk County Sheriff Steven W. Tompkins said this kind of isolation from mainstream society has deeper implications than ex-convicts not knowing how to use a fare machine or iPhone, though.

When inmates are still young, their minds are more malleable than older inmates, who tend to be set in their ways. Tompkins said this may mean that criminal behavior can be reinforced by spending time in prison at a young age.

However, Tompkins said there is still time to teach the young inmates constructive behavior that is different from what they might have learned growing up, referencing a conversation with an inmate he met early in his career at the Sheriff’s Department who returned to prison several times.

When Tompkins asked the man why he kept committing crimes, he said he learned to use crime as a survival tool from his father and grandfather. He knew crime was wrong, but said it was the only way he knew how to put food on the table.

Tompkins said that because of stories like this, he is going to begin segregating prisoners aged 18 to 24 from the older population in order to teach them constructive skills they’ve never learned before.

“We want to interrupt that cycle of criminality and introduce them to different options — different ways of leading their lives,” Tompkins said.

However, Tompkins said there is also value in having young inmates learn from the experiences of older inmates, and he plans to incorporate a mentor-mentee program into the prison system. This, he said, is based on a similar program in Connecticut that pairs older lifers with younger inmates who are in prison temporarily.

He said he was inspired while touring a prison in Connecticut when he met a mentor in the program who was serving a 999-year sentence for a double homicide he committed when he was 17. This man, Tompkins said, embodied everything that is wrong with the current justice system and the reasons why sentence lengths should be reduced.

“I didn’t know this guy at 17, but at 30, this was a well-spoken, very articulate, very insightful young man,” Tompkins said. “So when you talk about the need to let people go after a certain amount of time, that makes sense. What good is coming out of keeping this guy in jail for the next 900 years?”