Boston updates plans to become a zero-waste community

The city government has new plans to increase recycling efforts in different municipalities around Boston.

November 21, 2019

The City of Boston released its first Climate Action Plan, or CAP, which defined its goals to reduce carbon emissions and prepare for climate change, in 2007. The 2019 CAP update, released in October, outlines the specific actions Boston plans to take within the next five years in order to achieve carbon neutrality, or net zero carbon emissions, by 2050.

A goal the city has over the next five years is to become a zero-waste community and increase its recycling rate from 25 to 80 percent by 2035. The Zero Waste Boston Plan, released in June, could reduce carbon emissions by up to 60 percent by limiting the amount of waste being incinerated.

Victoria Phillips, the zero waste coordinator for Zero Waste Boston, focuses on engagement and outreach for the implementation of new plans and ensures different populations in the city understand the benefits of these government programs.

“From mining, to processing and distribution, to [getting finished products] to the consumer, that all contributes to the waste generated,” Phillips said. “The waste doesn’t just start once the product is no longer of use or of want [for] a consumer.”

Some efforts include creating new services to handle the increased capacity of waste diversion, such as waste collection services, drop-off centers and transfer facilities. The city has also pushed requirements, fees and bans to incentivize waste reduction.

Other measures include education and outreach initiatives to promote zero-waste behaviors for Boston businesses and residents. These efforts will aim to advance the sustainable consumption of goods and services, as well as encourage the reuse of materials and the development of a circular economy that allows residents to meet all of their needs locally.

Currently, the Zero Waste Boston Plan is focusing on the best ways to create short-term change. The Recycle Right campaign looks to educate Boston citizens about what can and cannot be recycled, and offers an online directory where citizens can search for an item they want to recycle to determine whether the item should be recycled or thrown away.

“It’s pretty amazing what can end up in a recycling stream, from Christmas lights to bowling balls,” Phillips said.

In July, the city sent out requests for proposals to introduce services for residential textile collection as well as the collection of organic food scraps. These requests are still under review.

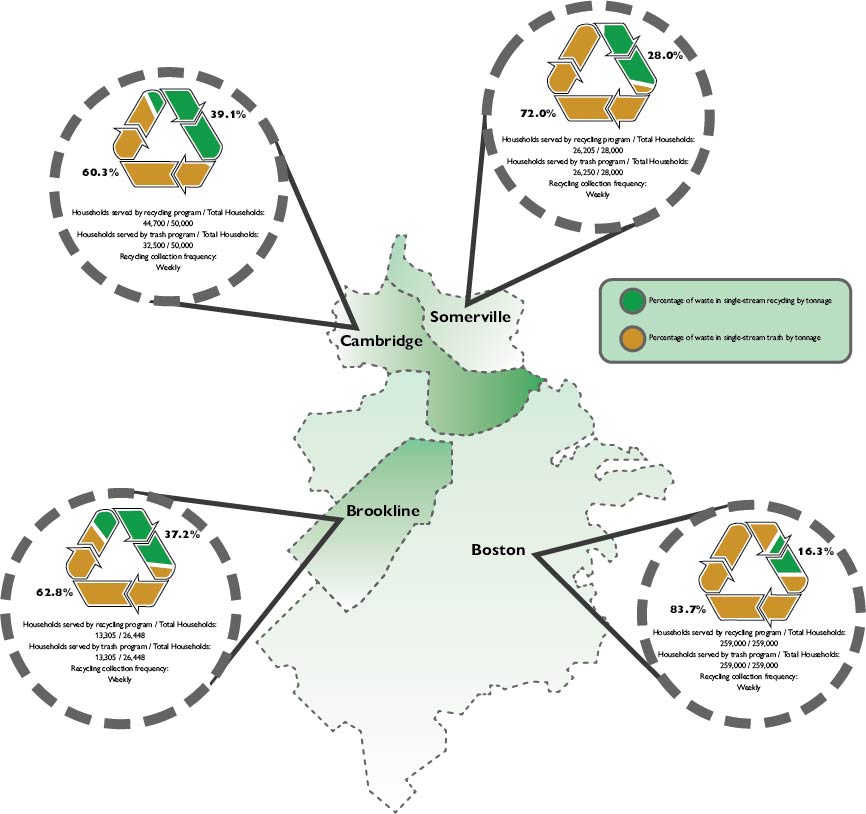

Municipalities in the Greater Boston area have implemented recycling programs with various degrees of citizen participation. Data from Massachusetts State 2018 Municipal Solid Waste and Recycling Survey Responses.

The Zero Waste programs were modeled after measures implemented in San Francisco, Seattle, Austin and Cambridge.

An important feature of these programs is the existence of creative, targeted outreach and communication. To do this, the city requires an adequate budget and a staff with a certain level of expertise related community engagement.

Jennie Stephens, director of the school of Public Policy and Urban Affairs as well as Dean’s Professor of Sustainability Science and Policy, notes the importance of community engagement in jumpstarting environmental change.

Stephens emphasized that shifting toward sustainability must include efforts to promote social justice.

“Boston is a very unequal city. And many [efforts to be sustainable] actually seem like good ideas [but] they actually end up perpetuating inequities and disparities among the different communities in Boston,” Stephens said.

Working toward a zero-waste future also involves commitment from Boston residents and students. While universities such as Northeastern work to tackle these issues within their own communities, many students live off-campus.

One way that students can help reduce their waste is by reusing, giving away or selling materials they use in their apartments. Other small actions anyone can take include bringing reusable cups and bags to places where you would otherwise have to buy them.

Clara Winguth, a first-year environmental science major, believes the best way to reach out to young people is through social media.

“Younger people are on Twitter and [other] social media and they’re raising their voices, you know, [raising] their concerns, but I feel like if the City of Boston was also there and there was an easier way to communicate with the city,” Winguth said. “You know, I care but it’s like, ‘All right then what can we do about that?’”

To achieve its waste-free goal, Boston will have to view the issue of climate change from a global perspective, while ultimately reflecting the interests of its residents.

“I think the opportunities to get involved and what direct action you can take can definitely be [muddled] and a little confusing, and particularly around waste because what you can recycle or compost from one vendor to another or even from one state to another can change,” Phillips said. “It’s important for our messaging to be very clear and Boston-specific.”