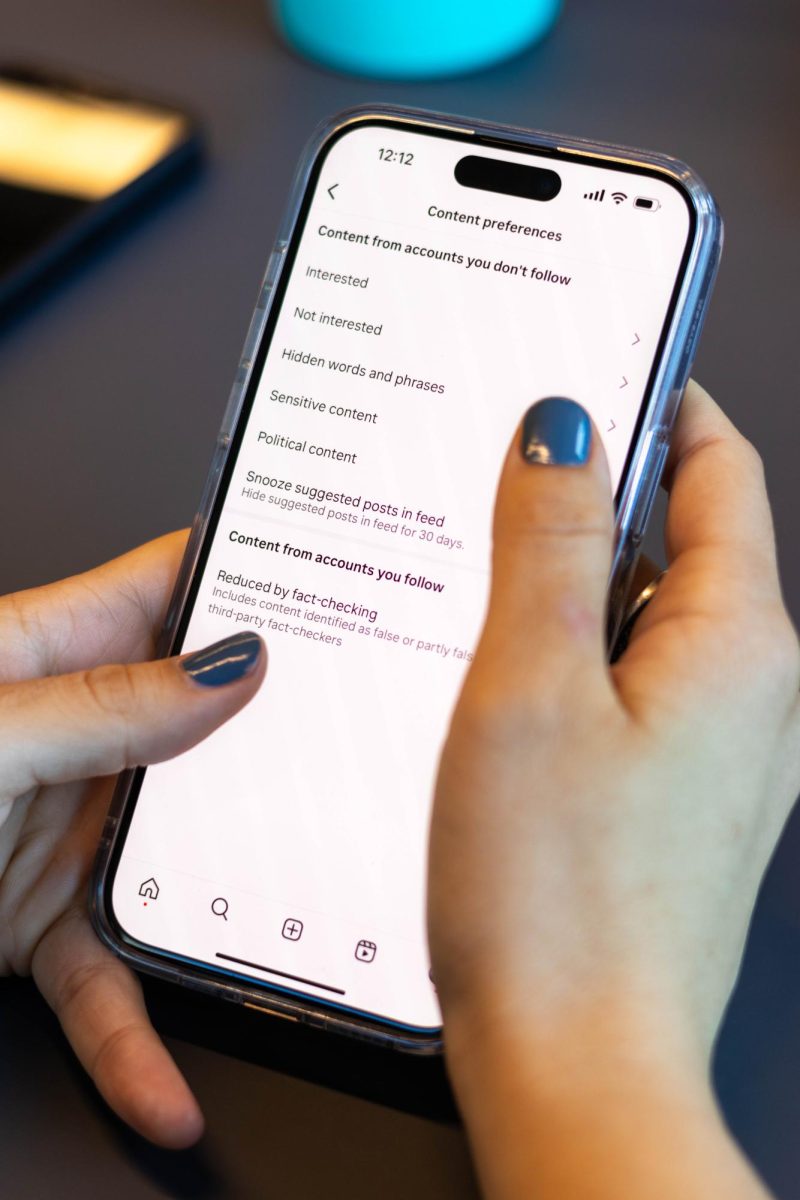

Review: ‘Everything Everywhere All at Once’ transcends genre

Michelle Yeoh stars in “Everything Everywhere All at Once.” The film takes on both fantastical mutliverse storytelling and grounded family conflict. Courtesy of A24.

April 20, 2022

Comedy, romance, sci-fi, kung fu. With so many diverse elements, Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert’s genre-defying masterpiece “Everything Everywhere All at Once” undoubtedly delivers on its titular promise.

The film opens on a chaotic day in the life of Evelyn Wang (Michelle Yeoh), the owner of a struggling laundromat. Evelyn attempts to simultaneously prepare for a meeting with a tax auditor at the IRS and plan a Chinese New Year celebration to please her father (James Hong), who has just arrived from China. Her daughter Joy (Stephanie Hsu) wants to introduce her grandfather to her girlfriend Becky (Tallie Medel), but Evelyn fears her father is too traditional and dismisses Joy’s request. Meanwhile, Evelyn’s husband Waymond (Ke Huy Quan) repeatedly tries to serve her divorce papers, but she is too preoccupied to notice.

Evelyn’s day gets even more chaotic when, while inside the IRS building, Waymond is replaced by a version of himself from another universe, who informs her that her safety is at risk because an evil force called Jobu Tupaki, a version of Joy, is traveling from universe to universe in search of the most powerful version of Evelyn. From there, the movie proceeds with wacky absurdist humor, complicated conceptualizations of quantum physics and riveting kung fu fight sequences that pay homage to Yeoh’s long history of starring in kung fu films.

Yet, at its core, “Everything Everywhere All at Once” is about family. Over the course of the two-and-a-half-hour run time, Evelyn realizes how her painful relationship with her father has damaged her marriage and her parenting, and discovers that mending her relationships in her own universe will spread positivity to the surrounding universes.

The film explores generational trauma through the lens of absurdism, or the belief that life’s absurdity should be treated as a source of comfort or amusement rather than a source of existential pain.

Evelyn’s father disowned her when she decided to move to the United States with Waymond to start a laundromat together. Even though they have since made up, the laundromat is still a failure in the eyes of her father. Evelyn’s sense of inadequacy only grows when she learns that multiple universes exist, in most of which her decision to stay in China allowed her to become far more materially successful than she is now.

In every universe, Evelyn passes her feelings of shame onto Joy, which creates Jobu Tupaki, an amalgamation of Joy’s most negative emotions. Evelyn must make peace with all the lives that she did not live and acknowledge the beauty in her own life before she can pull Joy back from the depths of nihilism and resentment. When Evelyn and Joy stop dwelling on the things that the other is not, they can begin to heal.

“Everything Everywhere All at Once” does not shy away from infusing scenes bearing heavy emotional baggage with comedy. The entire film is imbued with a sense of erratic hilarity, allowing audiences to find respite from their tears with surprised laughter. For a film that spends a large portion set in an IRS tax auditing office, there is never a dull moment.

One of the most honest conversations between Evelyn and Joy takes place in a universe where both are small boulders overlooking a vast canyon, with the heartfelt dialogue displayed in subtitles above the two rocks. At the climax of the film, when Evelyn recognizes that infinite possibilities do not have to mean infinite disappointments, she places a googly eye on her forehead to symbolize her enlightenment. Even in universes as outlandish as a world in which humans have hot dogs for fingers, there are profound and earnest moments. “Everything Everywhere All at Once” will devastate viewers, but it will do so with a consoling joke and a smile.

Unlike other prominent recent meditations on generational trauma — such as Disney’s “Encanto” and Disney and Pixar’s “Turning Red” — “Everything Everywhere All at Once” is told from the perspective of an older generation, affording the flawed parent with more sympathy than the aforementioned child-centric films. Yeoh’s performance reminds the audience that the process of recovering from emotional scars is not a journey that ends after having children. Parents are fighting their own battles.

For young audiences who tend to resonate with Joy over Evelyn, this film offers much-needed insight into the parental psyche. Many diasporic films acknowledge the novelty of immigrant families’ migration to the U.S., but until “Everything Everywhere All at Once,” those stories tended to stray away from the cost of that trek.

Evelyn and Joy’s reconciliation is a hard-won moment of healing between generations. When Evelyn tells Joy, “Of all the places I could be, I just want to be here with you,” audiences are able to imagine their mothers saying the same thing.

One ridiculous universe at a time, “Everything Everywhere All At Once” teaches audiences to accept their family despite what they are not and to be proud of them for what they are.