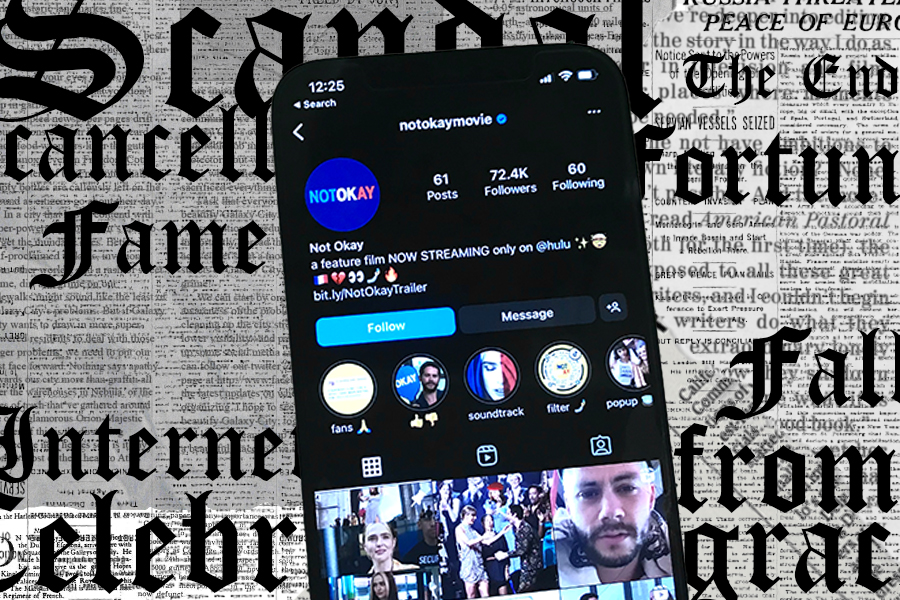

Review: Hulu’s ‘Not Okay’ explores the toxicity of fame on the internet

“Not Okay” examines the addicting, if unpredictable, brevity of fame found online. Directed by Quinn Shephard, the film premiered on Hulu this summer.

September 7, 2022

Movies about getting too famous too fast and sacrificing integrity to get there are nothing new — but Quinn Shephard’s sophomore film “Not Okay,” which premiered on Hulu July 29, gives the genre a new context. In the age of TikTok and social media, virality has never been more within reach, and it’s possible for anyone to be famous as long as they have a story.

Danni Sanders (Zoey Deutch), a friendless photo editor employed at a Buzzfeed-esque digital magazine called Depravity, decides to put her Photoshop skills to use by posting pictures from a fake trip to Paris. She succeeds in attracting the attention of her workplace crush Colin (Dylan O’Brien), a perpetually-stoned influencer who serves as cringey comic relief. But a fake photo of herself at the Arc de Triomphe that she posts just minutes before a devastating terrorist attack sends her lie into a disaster-spiral. After fielding worried texts from family and Instagram mutuals, Danni makes the decision to pretend she was present for the bombing rather than admit to her mistake. From there, her fame skyrockets, resulting in a promotion at work and an unsatisfactory hookup with Colin. Eventually, she takes her lie too far and inevitably gets caught, and her fame plummets into scandal.

Danni’s character is meant to be as unlikeable as possible. Virtually every decision she makes is completely indefensible, and she doesn’t experience any character growth, let alone a redemption arc. Her worst offense is attending a support group for survivors of terrorist attacks to make her story more believable and befriending Rowan Aldren (Mia Isaac), a young anti-gun violence activist who survived a school shooting that killed her older sister. Danni gets close to the girl to leech off of her fame, and even when she starts to become genuinely fond of her, she doesn’t feel true remorse for her lies until a suspicious co-worker threatens to expose her. Even at the end of the movie, she confesses that she doesn’t feel she’s learned anything.

Herein lies the ultimate question of Shephard’s film: Danni is loathsome in every way imaginable, and each scene demands that the audience jeer and throw popcorn at the screen; so when the death threats and hateful insults start rolling into Danni’s inbox, should the same audience feel sympathy?

The internet often thinks more highly of its celebrities than they may deserve. Aided and abetted by the warp-speed, worldwide reach of social media, fame is so instant and all-consuming these days that regular people are elevated to an idol-like status before fans even really get the chance to know them. Since virality comes so suddenly, it shouldn’t be a surprise that it’s equally sudden when that fame sours. If the backlash to mistakes that celebrities made was nuanced and constructive, the speed wouldn’t be a problem. But of course, criticism on the internet never is.

Danni represents the brand of instant celebrity that modern social media has bred: both prone to mistakes and thoroughly ill-equipped to handle the rapid shift from constant praise to overwhelming hatred. Danni’s case is an extreme one, because she’s actually guilty of everything people are accusing her of, but the film still does a good job of charting the catastrophic rise and fall of fame in the internet age.

Although initially it might seem as though Danni gets everything that’s coming to her and more, the consequences for her actions are ultimately rendered ineffective in teaching her any kind of lesson. Though her parents aren’t happy with her, she’s able to move back into the comfortable home she grew up in at no cost, and it appears that as long as she wears a baseball cap, she’s largely — albeit inexplicably — unrecognizable in public. Danni’s wealth, whiteness and attractiveness all shield her from the repercussions she would receive if not for her privilege, which makes it even more difficult to summon up any sympathy for her. She’s unhappy, but she’s always been unhappy; now she just has a better reason to be.

It’s unclear whether “Not Okay” is Shephard weaving a cautionary monkey’s paw tale with a modern spin or just testing how much she can get audiences to hate Zoey Deutch. Either way, the film is undeniably hellish to watch. Newcomer Isaac delivers an earnest standout performance as the film’s only likable character, but even well-loved actors like Deutch and O’Brien play characters that are detestable and at times painful to watch. “Not Okay” is 103 minutes of pure secondhand embarrassment, and although Shephard leaves whether or not to feel sorry for Danni up to the viewer, not even the exceptionally kind Rowan is able to forgive her.

The style, dialogue and plot of “Not Okay” make the film perfectly representative of the current phase of the internet (or maybe the 2021 internet). The “getting famous” story arc itself is nothing new, but Shephard did a remarkable job of contextualizing the classic tale within a specific cultural moment. With Danni’s technicolor avant basic wardrobe and ubiquitous pop culture references, “Not Okay” already feels slightly dated, and it’s impossible to say whether this time capsule of a film will be deemed amusing or mortifying in ten years. Maybe choices like Danni’s thick blond front streaks are commenting that the trend cycle moves almost as quickly as the fame cycle does. Or maybe Shephard just wanted to embarrass the internet by holding up a mirror to it.