Soccer teams create conversation about mental health on and off the field

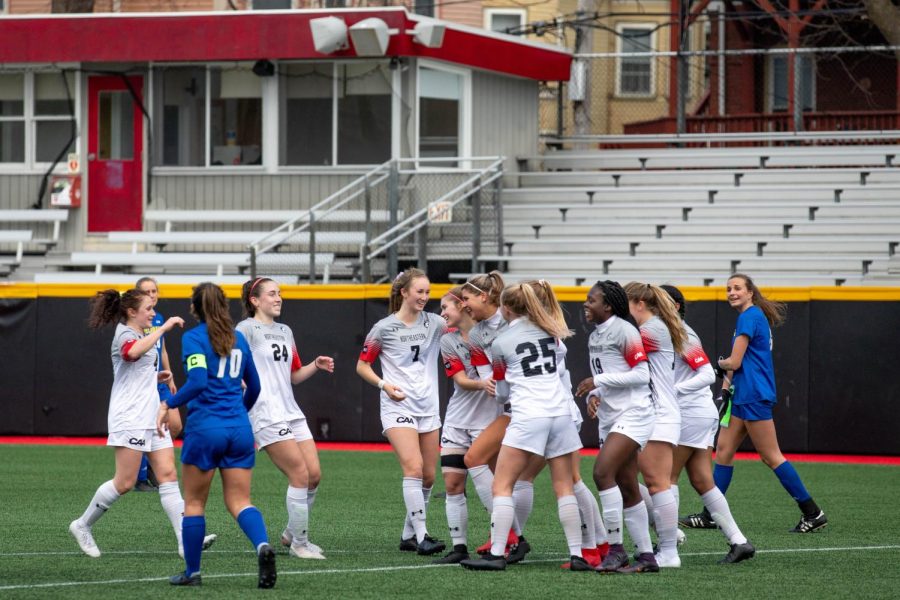

The women’s soccer team celebrates after a home win against the University of Delaware

September 30, 2022

The Northeastern University men’s and women’s soccer teams are playing home games this week in honor of a cause close to their hearts: mental health. The women’s team faced Stony Brook University Sept. 29, winning 3-0, and the men’s team will play University of North Carolina Wilmington Oct. 1 in games dedicated to bringing awareness to the issue.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, the conversation about mental health has increased throughout the nation, the sports world included. On the public stage, athletes such as Simone Biles, Michael Phelps and Serena Williams have been leading the charge. On NU’s campus, athletes and coaches have been working to create the space for their teams to open up and feel comfortable getting the help they need.

“Every year we try to do a few games where we’re raising either money or awareness … using our platform as athletes,” said women’s soccer assistant captain and graduate student midfielder/defender Sydney Fisher. Reflecting on the heaviness of this past year in the NCAA with at least five collegiate athletes dying by suicide, both teams felt the call to do their part in normalizing talking about mental health.

“I think as coaches it’s an opportunity for you to look in the mirror and make sure that you’re doing everything you can to make sure and help and hope that’s never one of your athletes,” said women’s soccer head coach Ashley Phillips.

Given the rigorous schedules and pressures student-athletes face, these conversations are vital.

“Being a college student is challenging; you’re 18- to 20-something-years-old, on your own for the first time, a little less structure. All of these things are changing. And then all the sudden you throw in Division I sports which is basically a full-time job,” Phillips said.

Playing at this level creates a profile for student-athletes and expectations to meet.

“People are looking at scores, they know when you lose games, they know if you play or not. There’s pressure from your coaches: whether you’re starting, or getting minutes or competing for any time on the roster,” Phillips said.

NU Director of Athletics and Recreation and former men’s hockey coach Jim Madigan also finds the culture of athletics to play a part in hindering athletes’ mental health journeys.

“As athletes, it’s ingrained to say ‘We overcome injuries. … You’ll fight through it, you’ll be okay.’ So we’re taught that at an early age, it’s part of our psyche, it’s part of our DNA,” Madigan said.

This mentality can promote a stigma about opening up and admitting that you need help.

Men’s soccer redshirt senior midfielder Michael Stockley has battled this stigma. Stockley has been injured for most of his NU career and said the impact it’s had on his mental health has been significant.

“My freshman year I was like, ‘I want to leave here playing professionally.’ So imagine all the places my head has gone to as I’ve progressively felt like that’s getting further and further away,” Stockley said.

Instead of turning to his team for support, he turned inward. While trying to take some time alone to sort through his emotions Stockley said he ended up isolating himself from his team, drawing out this period for three years after the injury.

Upon finally returning to the field, Stockley got hurt again.

“The depression I went into, I’ve never been that low in my entire life. But something in my mind just told me, ‘You know what you can’t do is the same thing that you did before. Because look at how long it took you just to be able to communicate what was going on,’” Stockley said.

He began speaking openly with the team about his mental health struggles and was surprised by the result, not expecting how many teammates would thank him for sharing.

The new head coach for men’s soccer, Rich Weinrebe, has also made it his goal to open up communication within the team and give players like Stockley the space to share their stories. At a pre-season retreat in New Hampshire, Weinrebe introduced the Four H’s, an opportunity for players and staff members to talk about their history, hopes, heroes and heartaches, setting the example by going first himself.

Since then, players and staff members have been able to share their Four H’s on a volunteer basis and often the conversation has shifted toward mental health.

“When we started doing it, everyone was a little bit nervous and almost trying to avoid it, because they’re scared to be vulnerable. But I think we had good leadership from the older guys like Michael and Timmy [Ennin] that really showed us how [much of a] family we really are, how much you can really open up to the group,” said junior defenseman Sebastian Soriano. “I think that started a trend where younger guys on the team, coaching staff, trainers, everyone that’s a part of the team, were able to really open up, feel comfortable, feel safe and feel like, ‘Okay, yeah, we have something special here.’”

Fisher also credits her coaches for creating an environment the women’s soccer team feels comfortable talking about mental health in. Having her mentors and coaches talk about their struggles has inspired Fisher to do the same, she said.

“What our coaches do for me, I’ve tried to model with my underclassmen and open up and try to be vulnerable, so that they too feel like they can be like that,” Fisher said.

For her, the resources the university offers are also a key element to maintaining her health on and off the field.

Last year, right after transferring to NU for graduate school, Fisher injured herself in a preseason scrimmage.

“Being in a team environment and having to be there and just watch, I had to get really good at managing some of my demons and dealing with my own mind, honestly. I sought out a lot of those resources,” she said.

At the beginning of each year, the Sports Performance team meets with athletic teams to let them know about the resources available. This includes athletic trainers, doctors, specialists and strength and conditioning coaches as well as sports psychologists, mental health counselors and sports performance personnel, Madigan said. The Sports Performance team works to build a relationship with athletes so when they do need help they know exactly what their options are.

“We bring [mental health professionals] in for the group just to kind of get a hands-on face-to-face person that they can go to and reach out to. But they also meet sporadically throughout the season as a collective group just to make it common. We think it’s good to normalize it,” Phillips said.

From access to these resources to the active and intentional creation of an environment fit for vulnerable conversations, Northeastern’s soccer teams have benefited greatly from mental health awareness.

“It’s been really cool in terms of how much closer I think [breaking the stigma has] brought teammates together. You realize, as cliche as it sounds sometimes, you’re not alone in this, and no matter what you may be going through, however big or small it feels to you or is perceived, we’ve all dealt with issues,” Fisher said. “I think to be able to say, ‘Hey, these are some resources that I went to when I was struggling, or am still struggling, and it really helped me in this sense, but also I’m here to listen, but I can also provide resources.’ Just to feel like you’re not alone in it has been incredibly awesome.”