Review: ‘Blonde’ lacks anything substantive beneath its gorgeous facade

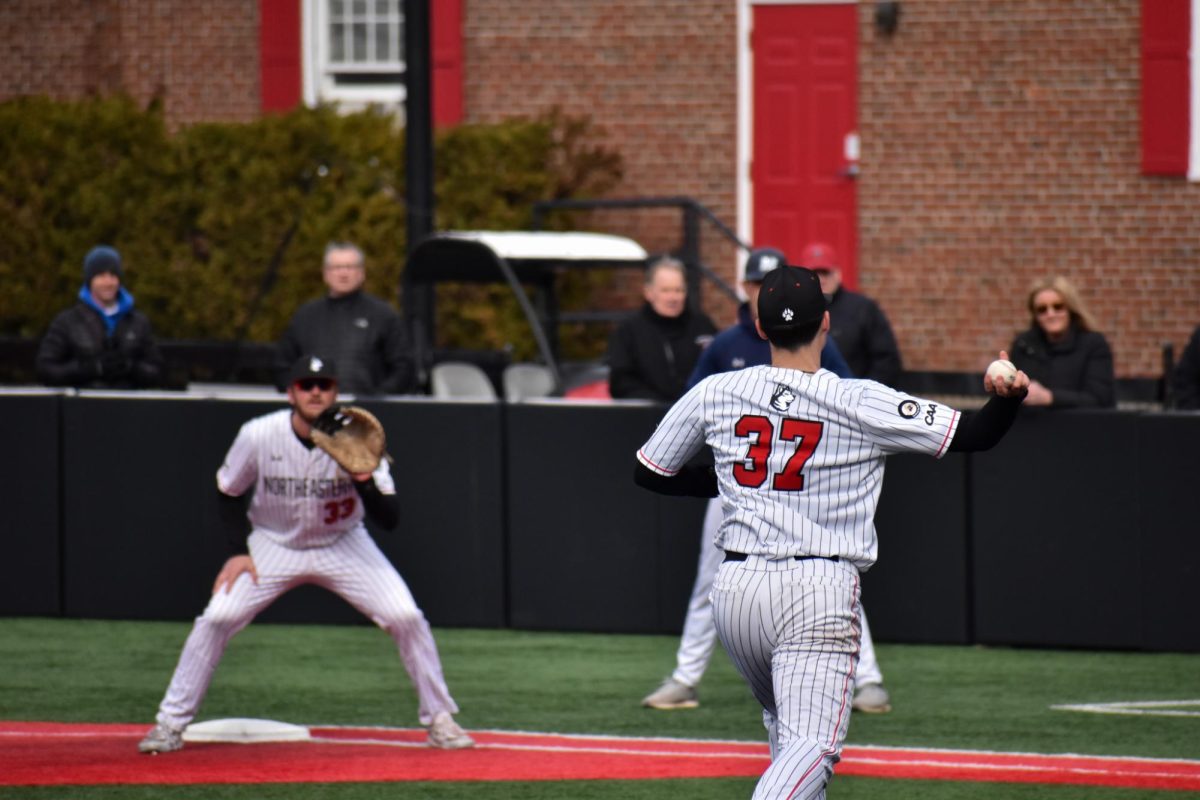

Ana de Armas stars as Marilyn Monroe in Andrew Dominik’s “Blonde.” Photo courtesy of Netflix. © 1997-2016 Netflix, Inc. All rights reserved.

October 5, 2022

After 10 years of production stalls, casting switch-ups and distribution struggles, Andrew Dominik has finally completed his quest to bring “Blonde” — author Joyce Carol Oates’ fictionalized account of the doomed life of Hollywood’s favorite bombshell, Marilyn Monroe — to the silver screen. The result of the Australian writer-director’s exhaustive efforts is a cumbersome film that, despite its superb craft and array of solid performances, is utterly incapable of overcoming its incredibly reductive view of the woman at its center.

The Netflix release, which received a rare — and telling — NC-17 rating, primarily follows Norma Jeane Mortenson (better known by her stage name, Marilyn Monroe) from her traumatic childhood to her abuse-ridden adulthood, before finally concluding with her 1962 suicide. Even before the film’s Sept. 28 release, news of Dominik’s approach to Monroe’s life was the subject of controversy online, with many, understandably so, decrying its inclusion of graphic sexual assault and lack of historical accuracy, amongst other concerns.

One of the few aspects of the picture that even the most ardent of detractors have celebrated is Ana de Armas’ portrayal of the titular icon, which is absolutely stellar. Save for the few instances in which her natural accent slips in, de Armas fully embodies the attributes audiences associate with Monroe — such as her light, breathy voice and relaxed, carefree disposition — while allowing herself to channel emotions like fear, grief and rage that Monroe seldom exhibited on screen. It is a shame, however, that de Armas is unable to display the more joyous side of her character’s life. This is not de Armas’ fault and is instead more so a casualty of Dominik’s frustratingly incomprehensive screenplay and direction.

Luckily for Adrien Brody, who portrays Monroe’s second husband, the playwright Arthur Miller, Dominik’s creative choices are largely unable to curtail him in the way they do to de Armas. Miller is arguably the closest thing “Blonde” has to a layered male character, and Brody exhibits the complexity of his character skillfully. This is most evident in a scene where Monroe and Miller discuss the character of Magda — invented by Miller for one of his plays — whom Monroe is set to portray on Broadway. In this scene, Brody quickly and believably fluctuates between dismissiveness and appreciation, effectively communicating that his character is, eventually, moved by Monroe’s reading of who Magda is. His character is no angel, however, which Brody displays in subsequent scenes where his admiration for Monroe appears to cool considerably.

The remainder of the film’s principal cast — consisting of Bobby Cannavale as Joe DiMaggio (Monroe’s first husband), Julianne Nicholson as Gladys (Monroe’s psychotic mother) and Xavier Samuel as Cass Chaplin (one of Monroe’s first lovers upon her ascent to stardom) — do what they can with what they are given, which is, unfortunately, very little. Dominik’s tunnel vision ultimately compromises the potential of everyone else involved.

Even the film’s remarkable craft is undermined by Dominik’s own lackluster attempts to derive meaning from the distorted depiction of Monroe he constructed. It does not matter that the film is visually stunning — even if its changes between varying aspect ratios, color and monochrome feel, at times, superfluous — if what the visuals depict is hollow and meandering. Similarly, the lavish recreations of famous locales in which Monroe spent her time, such as her shared home with Miller and the soundstages of 20th Century Studios, are unable to be fully appreciated in conjunction with Monroe’s distractingly deplorable characterization.

It is this frankly cruel assessment of Monroe that ultimately undoes the hard work of the film’s many collaborators. Dominik’s decision to make “Blonde” adhere to the same few malicious plot beats — Monroe is taken advantage of, either sexually or emotionally; Monroe makes her “daddy issues” abundantly clear; Monroe emphasizes that “Marilyn” and “Norma Jeane” are not one and the same (noting every time that the latter suffers so that the former can succeed); Monroe has an explosive breakdown; rinse and repeat — for three hours straight culminates in a film that oscillates between banality and occasional, needless provocation.

Further worsening this cycle is Dominik’s lack of subtlety and belief that his audience can only understand his view of Monroe — that she was nothing more than a deeply depressed woman incapable of combatting the abhorrent actions of the men in her life — if he bludgeons it into them with the ferocity of a sledgehammer.

Had Dominik approached “Blonde” from a more holistic and compassionate angle, the film could have been an awe-inspiring and insightful portrait of an American pop culture icon; as is, the film is anything but.