Boston protests of Mahsa Amini’s death continue at BPL

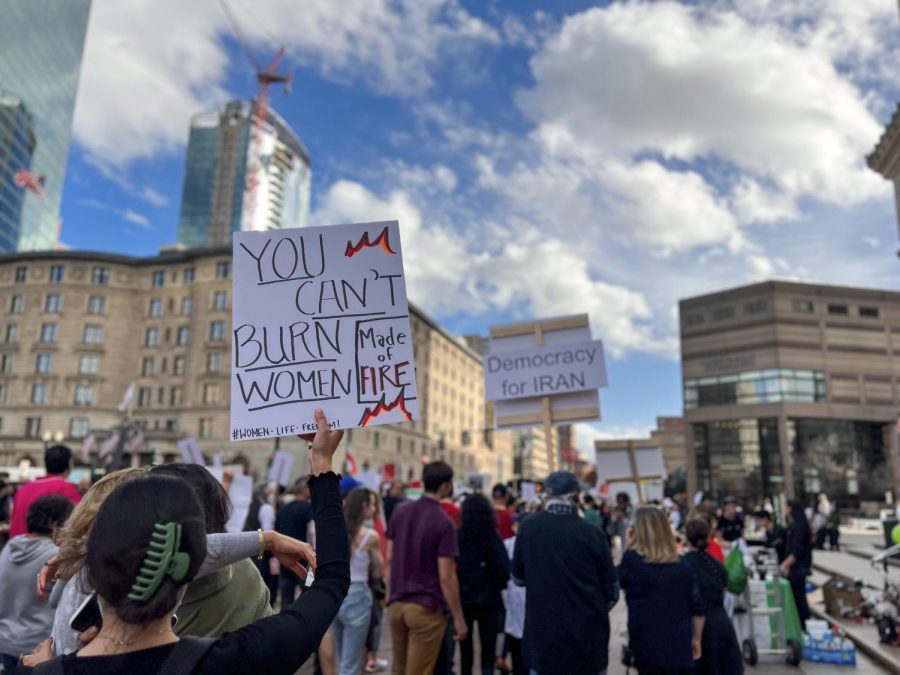

A woman raises a sign protesting the Iranian government Nov. 5. Protests like these have spread all over the globe in wake of Mahsa Amini’s death.

November 13, 2022

“It’s a beautiful day for a protest,” remarked a passerby looking over to the street in front of the Boston Public Library, where dozens of both Iranian and non-Iranian supporters gathered Nov. 5 in solidarity with the ongoing protest movement in Iran, sparked by the resounding death of Mahsa Amini.

Amini, the 22-year-old who was arrested Sept. 13 by the Iranian morality police for allegedly wearing a loose hijab in violation of Iran’s hijab law, died Sept. 16 while in custody. While the government insists her death was due to an “underlying disease,” her family said the police beat and struck Amini until she fell into a coma and died at the hospital three days later.

Protests first erupted at Amini’s funeral in her hometown in the Kurdish region of Iran, and demonstrations have expanded around the world, now in their sixth week. Beyond Iran’s major cities, solidarity events span from neighboring Afghanistan and Turkey, to countries including the United Kingdom, Sweden, Greece, Italy, Germany, Lebanon, Spain and major cities across the United States.

In Boston, Independent Iranians of Boston organized the Nov. 5 demonstration, during which protesters handed out roses and leaflets titled “What it’s like living in Iran under the Islamic Republic.” They waved around the country’s flag, even wrapping its green, white and red colors around the neck of “Art”, one of the 84-inch bronze ‘Sisters of Literature’ statues sitting in front of the library. The organization held another demonstration in front of the Boston Public Library Nov. 12, also in support of the current Iranian uprisings.

“Woman, Life, Freedom” — a Kurdish rallying cry symbolizing the global feminist solidarity movement — reverberated through the area, along with rhythmic chants of, “justice for Iran” and “down with [the] Islamic Republic.”

At its heart, the protest movement is an uprising against the Islamic Republic’s four decades of patriarchal oppression and violence against women. History shows that women in Iran have always performed acts of resistance, including the Pink Revolution in the 1990s, the One Million Signatures campaign achieved by Iranian feminists in 2006 and the Girls of Revolution street protests that erupted in 2017 after a 31-year-old mother took off her headscarf and waved it in the air in central Tehran.

However, the protesters in attendance say it’s different this time around.

Camilia, one of the organizers of the protest who wished to be identified only by her first name because of safety concerns, told The News that the current uprisings are primarily distinctive and powerful for being women-led, as well as supported by the people’s unity against the regime.

“What’s amazing about this time around and this revolution is that the people are showing that they were never the government… We are being loud enough to distinguish ourselves so when we go in the streets and say we’re Iranian, we’re not associated with that terrorist regime anymore,” Camilia said. “People know that the people of Iran have never been with the Islamic Republic… We’re all the same. They’re all brothers and sisters, [and] they’re dying.”

Another unique aspect of the current uprisings is the major participation of Iran’s Generation Z. Camilia said it is due to an increased access to TikTok and other social media platforms that younger generations in Iran are more aware of what those living outside of Iran have the freedom to do.

Though Camila has now been a Boston resident for six years for university and work, she said she lived in Iran for many years and has been stopped by the morality police herself.

“Every day [I] have this overwhelming feeling of guilt that I, for whatever reason, ended up not there [in Iran], but I very well could have been,” Camilia said. “It’s this struggle between guilt and ‘OK, now what can I do about it?’ … How are we going to make a difference to at least use [our voice] and try to bring that guilt a little bit lower.”

Many of the protesters in attendance disguised themselves with Guy Fawkes masks in fear of potential identification and persecution by Iranian agents. The mask — made famous as the one Hugo Weaving donned in V for Vendetta while playing a vigilante fighting the dystopian fascist government of the U.K. — has become a universal symbol of resistance.

Another protest organizer with the Independent Iranians of Boston, who asked to be referred to as Gol because of safety concerns, spoke of the organization’s intention behind holding the demonstration on Nov. 5. It’s the same day that Guy Fawkes, an English conspirator, attempted to blow up Parliament in the Gunpowder Plot of 1605.

On Nov. 6, Pouria Salehi, a postdoctoral associate in mathematics at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and another protest organizer with the Independent Iranians of Boston, shared a statement with The News that the organization had previously given at a demonstration Oct. 22 in Washington, D.C.

“In the past four decades, the absolutely criminal Islamic regime has brought the majority of Iranian society to a point where they see no path to freedom except to overthrow the regime,” the statement reads. “We, the Iranian diaspora community, know that the best way to show solidarity for our oppressed compatriots and the freedom of our beloved country is to bring the cries of our compatriots inside Iran to the ears of the world.”

Addressing the “global community” and “the governments of the free world” are two priorities listed. The statement ends with a call for nine action points — from legal prosecution of regime officials and their dependents to providing the right to decide the political future of Iran to the people of Iran, without foreign interference.

Toward the end of the Nov. 5 protest, the crowd began to sing “Baraye” by Shervin Hajipour, which roughly translates to “Because of” in English. The song’s haunting lyrics, describing trivial reasons young girls and women in Iran can be persecuted and killed, ultimately end with the movement’s mantra.

“For the girl who wished she was born a boy / For women, life, freedom / For freedom,” the lyrics read.