Can you trust your friends? Do you really know your allies? Do you know how to survive?

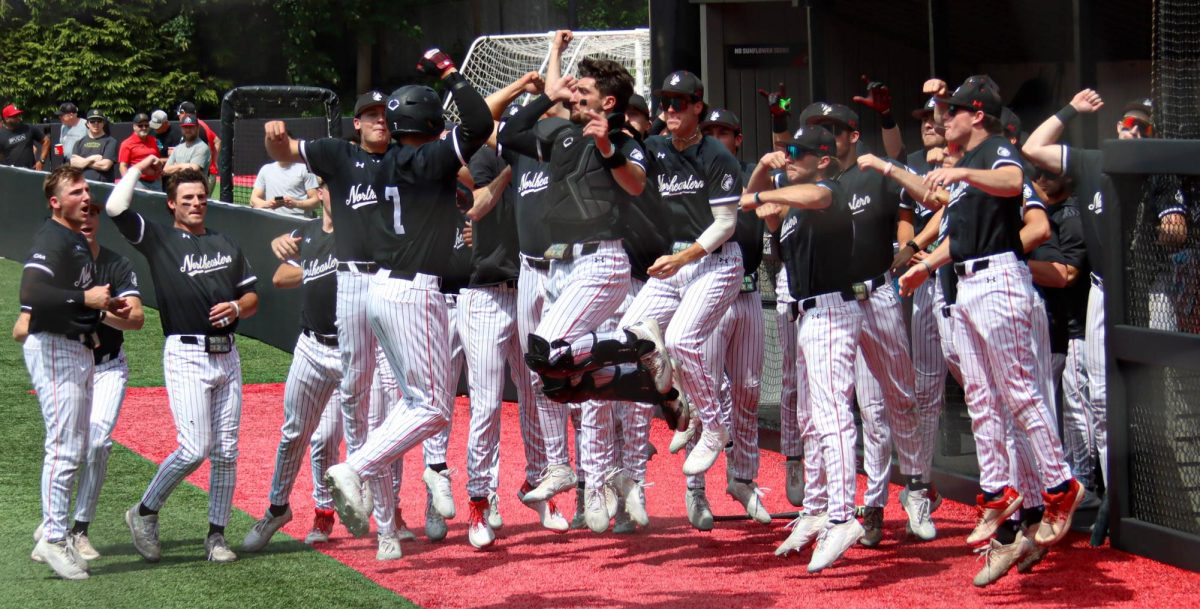

These are the questions that contestants have to answer for themselves in the game of “Survivor.” On a chilly moonlit night in late September, players and production staff of Survivor: Northeastern gathered on Centennial Common for the second challenge of the club’s 13th season. The excitement and anticipation was palpable as teams warmed up for their challenge: knocking down other tribes’ lanterns in the dark using bean bags.

Survivor: Northeastern, a club reproducing the format of hit CBS show “Survivor,” began its fall season on a rainy Sunday, Sept. 24, in the Back Bay Fens. This season, which is themed “The Wild, Wild West Village,” is now in full swing, with fifth-year mechanical engineering major JohnMichael “JM” Manzi serving as club president and host, who first played in season eight.

A season of Survivor: Northeastern lasts one semester, and two seasons are held a year. Tribals and challenges are hosted once to twice a week in lecture halls and on various quads around campus. Most tribals take half an hour, while challenges can last for hours, Manzi said. The season winner takes home a $250 cash prize, though it’s customary for the winner to use the money to take everyone out for dinner, said head of logistics and third-year computer science major Liz McDowell, who played in season 10.

The club began in the spring of 2017. Northeastern alum Casey Abel, at the time a third-year marine biology major, was inspired to start the club after finding University of Maryland’s version on an online “Survivor” forum. Abel has been a fan of “Survivor” since she was 10 years old, is an active member of online forums about the game and played mini challenges with friends in the past, but never on a larger scale until she founded Survivor: Northeastern.

For season one, Abel recruited friends and posted on Northeastern Facebook groups and sub-Reddits. The first season had 16 contestants, the minimum amount with which the game can be played.

“A lot of the challenges [in season one] were done with paper plates and plastic cups and just stuff that was really easy to work with,” Abel said. “The first season was kind of like a trial run.”

Тhe first season generated increased interest for the club, and members started making flyers and tabling events, hoping to encourage more growth. Six players came back to help revamp the second season. The structure of the club developed from there, and in recent years has had 16-20 players, who are overseen by a production staff that coordinates filming, game planning, finances and video editing.

The game, boiled down to its simplest components, consists of challenges and “tribals.” Challenges are the games that the production staff plan before the season begins. There are classic challenges like blindfolded games, puzzles and food, but most are unique to every season, Manzi said.

Tribals happen before every challenge; the tribe that lost the previous challenge meets in a room away from the other tribes for an opportunity to answer the host’s questions. This is a time for the tribe to reflect, talk to each other and, most importantly, vote someone out.

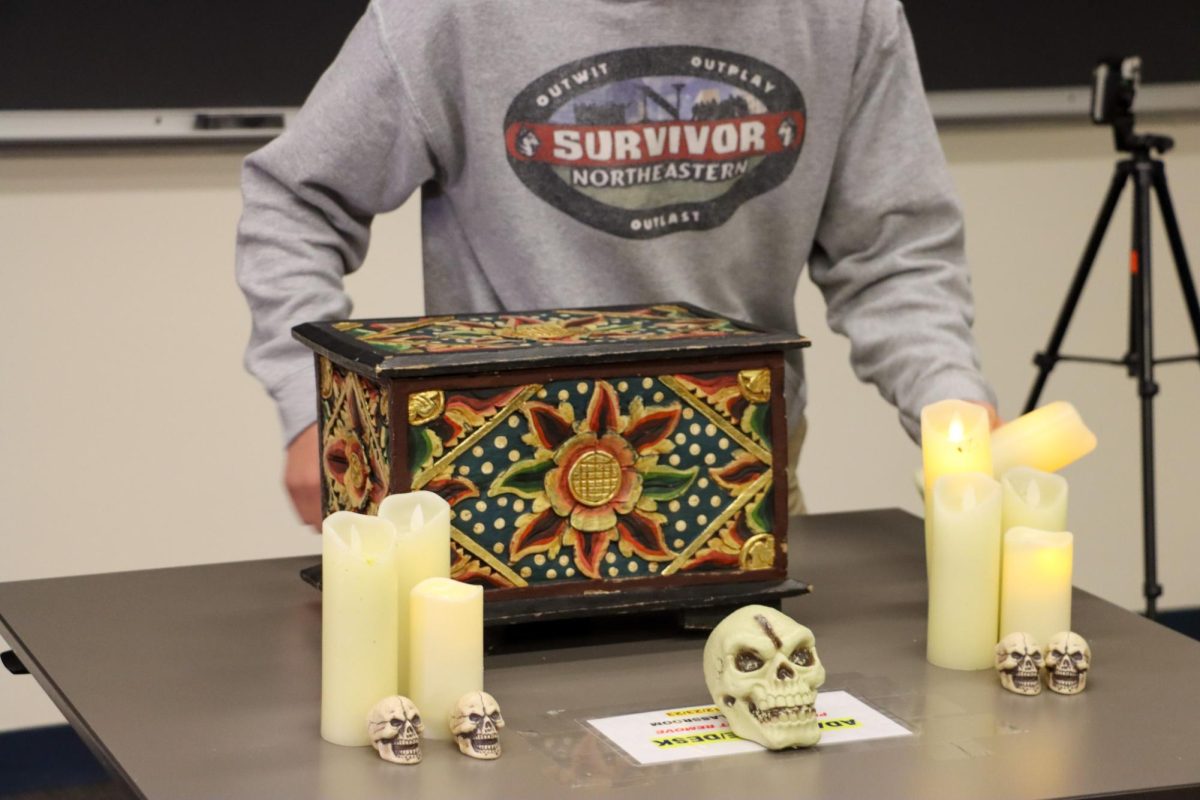

As votes are cast for who to eliminate, all the lights are turned off and battery-powered candles are turned on, surrounding the fateful box where votes are put in, and players of that tribe are invited in one-by-one. It is not uncommon for players to apologize as they hold up the slip of paper with the name of the person they’re voting to eliminate to the camera. Some take this time to confess to betraying their alliances; some laugh it off.

“Being in tribal honestly is a really scary experience sometimes,” said production staff Charles Roeger, a second-year political science and computer science combined major who played in season 12. “Especially the first few where you have no idea what’s happening to you, you don’t trust anyone, and you’re just praying to whatever force you believe in that the ‘Survivor’ gods will work for you.”

While players are casting their vote, the rest of their tribe waits outside in the hallway where they are monitored, ensuring no one is trying to sway their vote, according to third-year behavioral neuroscience major Emilia Smith, a production staff member who played in season nine.

Once the votes are in, the host calls the tribe back into the room together to sit down as the votes are read aloud.

“If you know that you’re safe, you’re probably not,” McDowell said. “I always say that if you’re not part of a blindside then you’re being blindsided. I’d be taking academic tests and be like, ‘At least I’m not at tribal council.’”

There are four tribes to start, but as the rounds move on and players are eliminated, players are swapped around and tribes are merged. The four original tribes season 13 started with are: the Aardvarks, Keewis, Cavaliers and Hershey & The Kisses. Currently, there are three tribes in the team after the most recent swap on Monday, Oct. 2.

As there is only one winner, elimination for most is inevitable. There are, however, tactics to delay or prevent being eliminated. True to the show, there are “idols” which are hidden around campus that guarantee immunity for a round. Players work to find clues around campus to find the location of idols.

Another popular method to avoid elimination is forming alliances. Some members of a tribe that know they will be going to tribal may decide to team up and vote off one person. But it is not uncommon for people to change their vote at the last minute.

“I was a very social player,” said third-year marketing major and head of filming Nicole Rios, who played in season 11. “I reached out to everyone. I think I had the most alliances for season 11 ever. I would set up alliance meetings almost every single day. And I dedicated so much time into playing, that was my whole life all semester.”

Once the show progresses to the point of the final few members, eliminated players act as the jury and pick the winners. This is why it is important to not burn bridges, as eliminated players are the ones deciding the winner, McDowell said.

The club is, to many students, all-consuming — McDowell has talked about the club in three job interviews and still routinely brings it up to friends, she said. Rios said for the semester she played, if anyone were to ask her friends what she was doing, they would most likely answer “Survivor.”

It’s this sense of passion that drives the club forward, as many members of the club are fans of the show itself, McDowell said. The production staff is keen on incorporating as many elements from the real show as possible. Seasons are planned in an hours-long production meeting before the first challenge, said head of game design Jack Burke, a third-year international business major.

Many people who played in a season will come back to help with production, Manzi said. “Everyone just wants the players and the other members of the club to have a good time and have the same good experience that they did. I think the social aspect of the club is what keeps people involved.”

But despite the nature of the competition, Abel said the community the club forms is one-of-a-kind.

“I think there’s something about going through an experience where your back might be up against the wall with another person,” she said. “That really bonds you in a different way, as opposed to just kind of sitting in class with someone and commiserating over a professor or something.”