Every year, the college admissions cycle happens like clockwork. Students make one of the most important decisions of their lives so far: where to go for college. To guide them during a notoriously difficult time, many students turn to college rankings.

One of the most popular lists of rankings for undergraduate institutions, medical schools, law schools and hospitals has been published by the U.S. News & World Report at the end of every summer for the past 39 years, but the value of these yearly rankings is being called into question more than ever before. This year’s report, published Sept. 17, incited responses from many schools resenting their ranking. The calculation criteria recently changed, causing many schools that were consistently highly ranked to drop down, while many public state schools moved up.

For its latest evaluation, U.S. News removed five ranking factors from the formula: “Alumni giving, class size, high school class standing, the proportion of instructional faculty with terminal degrees (achieving the highest degree possible in their field) and the proportion of graduates who borrowed federal loans.” Moreover, it changed the weight of nearly every category it used. This year, U.S. News used 19 categories to evaluate schools, whereas a year ago it had 17 categories. Categories added this cycle assess a school’s contribution to research, as well as graduation rates of first-generation students.

Colleges are always jockeying for the top few slots, which has caused controversy as some try to game the system. In February 2022, Columbia University math professor Michael Thaddeus published an investigation into the university for reporting “misleading” data to U.S. News. In 1988, Columbia was ranked 18th. For 2021-22, it ranked second, tied with Harvard and MIT. In the 2024 report, it sank to 12th place, tying with Cornell and the University of Chicago.

Columbia is not the only school that has been called out for fudging numbers. There have been numerous other incidents where colleges provided inaccurate numbers to bolster their position in the rankings.

Incidents like this call to question the very reliability of the numbers in an era where so much emphasis is placed on ranks. The pressure for schools to maintain a high rank has caused several medical and law schools opted-out from the ranks, as well as a few undergraduate institutions. Several admired institutions including Oberlin and Vanderbilt published statements after the report came out, defending their school and threatening to withdraw from the 40th cycle.

Rankings make a college look desirable when it’s high, so it is somewhat threatening to schools that have a history of being perceived as prestigious when they are closer to getting grouped in with state schools, which are traditionally thought of as providing a lower-quality education than expensive private schools. Colleges with higher rankings often advertise their prestige in marketing to prospective students.

A considerable amount of value and status is assigned to these ranks. But even U.S. news says on their website: “Don’t rely solely on rankings as the basis for choosing a college.” And as colleges threaten to withdraw, the ranks are being criticized and therefore losing some of the influence they once had.

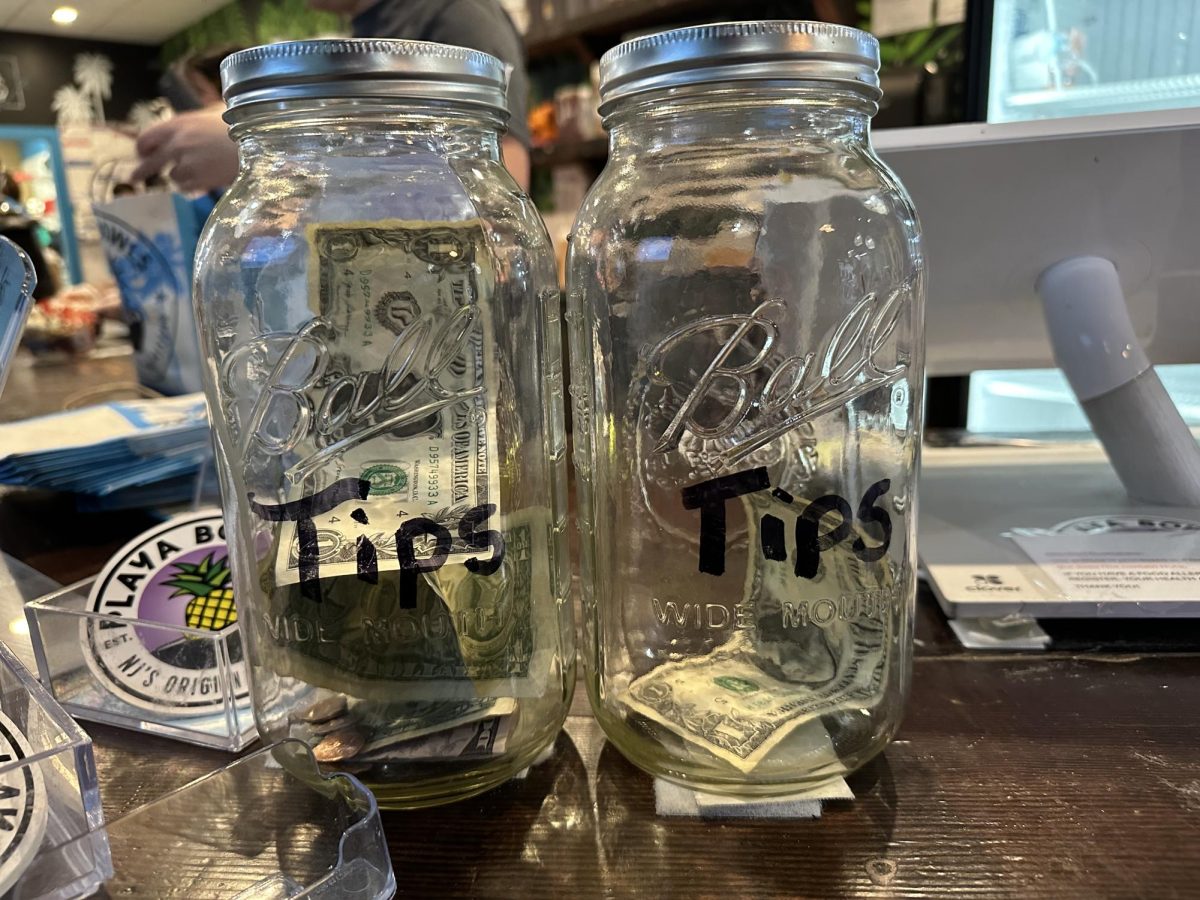

We have managed to make this sole report an authority for which colleges are the “best.” Phrases like “top 10” and “top 20” schools are common. Every year, hundreds of thousands of students compete against one another for spots at such schools. This is why acceptance rates have taken a nosedive across the board: There are more applicants, but the same amount of students are being accepted.

It’s a continuous cycle. Historically, selective schools are ranked highly. They wear their rank asa badge of honor and promote it to market their school to prospective students. Then, more students apply to their schools, which decreases their acceptance rate, making them look more elite, more unattainable and more prestigious. Last year, Northeastern notably concluded the application cycle with a 5.6% acceptance rate in their regular decision applicant pool.

These category shifts created a positive change. Put simply, the new criteria are more equitable since they don’t rely on existing connections and wealth. Moreover, they create a space for first generation generation students, coming during a time of growing populations of first generation college attendees.

At this point, it’s evident that these ranks, in many ways, are meaningless. Last year, Northeastern was 49th; now, we’re 53rd and tied with Case Western Reserve University, Florida State University, University of Minnesota (Twin Cities) and William & Mary. Did we change that drastically in a year?

I don’t see the logic in assigning value to a system that is inconsistent from year to year. If more categories are added or dropped, maybe Northeastern could reclaim a spot in the top 50. Or perhaps we could get pushed further down. At this point, it’s inconsequential, as a number will never accurately define the quality of a school. At the end of the day, the burden of success is on the student.

Zoe MacDiarmid is a first-year health sciences major. She can be reached at [email protected]