Jacob Pollock and a few friends started betting on sports games when they were seniors in high school. But once he discovered Fliff, a “social sports betting” platform that allows people of any age to participate, he noticed a significant shift: sports betting is normalized in society for fans of all ages.

Pollock, a 20-year-old second-year business administration major at Northeastern, says he encounters betting everywhere he goes on campus: at his fraternity’s house, in his dorm and at the dining halls. Discussions about odds, parlays and playmaking have taken over and it doesn’t show any signs of diminishing, despite negative stigmas related to its addictive nature and the fact that underage gambling, technically, is illegal.

“Honestly, it’s almost like a hobby now. You bet on sports, when you go to your friend’s house and you’re watching a game,” Pollock said. “You both have money on [the game] — maybe you’re rooting for the opposite teams and then it becomes intense. It’s just a thing that college students do. You get a big dopamine rush when you have it. It makes the game more entertaining.”

Pollock is one of many sports fans aged 15 to 20 who are betting on apps like Fliff before they reach the legal age of 21 to use official sportsbooks. While users never have to spend money on “social sportsbooks,” Pollock said many eventually choose to “upgrade” to official sportsbook apps.

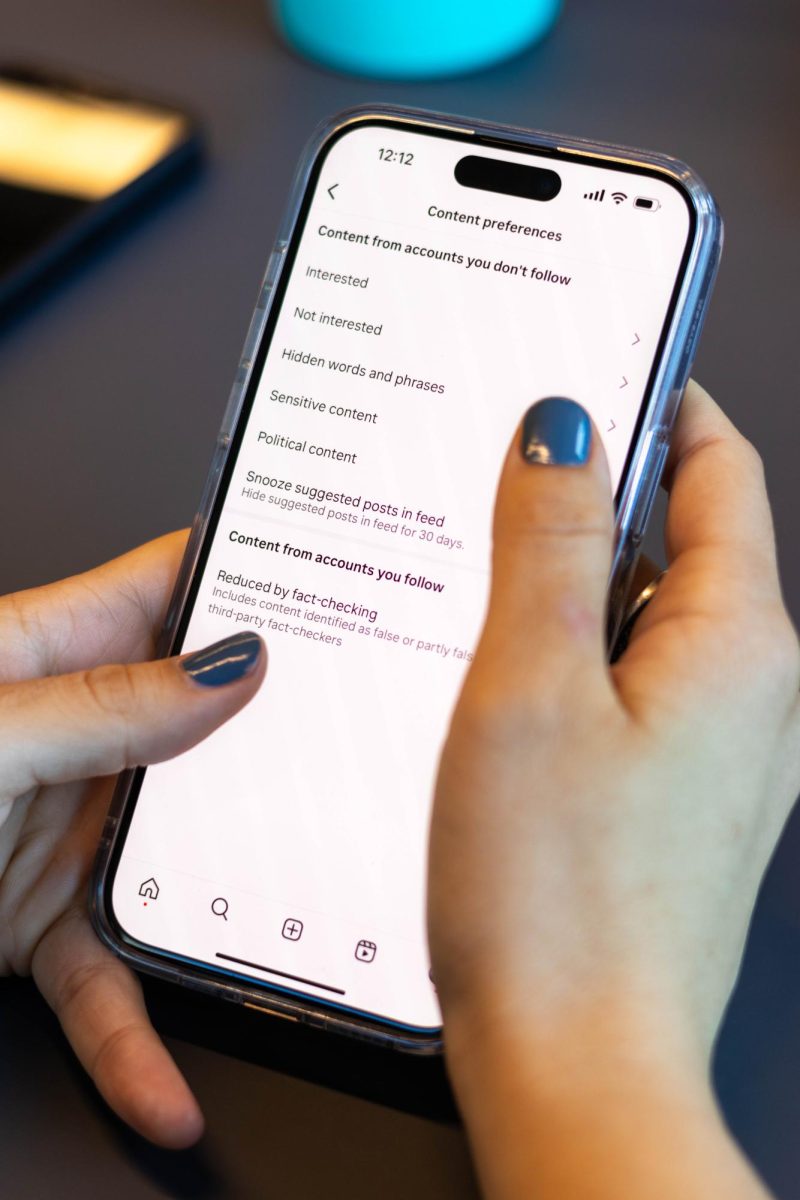

Online sports betting platforms have interfaces that are easy to interact with, feature live updates and statistics and offer a wide variety of betting options — all perfect for a busy college student, Pollock added, “that might also want to make a quick buck.” The apps make betting feel more like a leisure activity than a stressful experience, and tend to be an “improvement from social sportsbooks,” Pollock said. However, having access to sports betting on personal devices instead of at casinos and sports venues lowers the barriers of regulation that separate people under 21 years old from the gambling world.

As a result, college students and younger sports fans can now access betting at any time on their phones. College students are especially susceptible to getting hooked by betting platforms because campus culture is predominantly engaged with sports, said Richard Daynard, a professor at the Northeastern University School of Law.

“You used to just bet on a game for who was going to win,” Daynard said. “People have been betting on those things for probably as long as there have been such games, but these [platforms] are totally different. This is something that’s an addictive product that you’re getting continual reinforcement on.”

After an account is opened on an online sports book, it can be shared between multiple users and devices. Young fans, especially college students under the legal age of 21, access the platforms through friends or family who open an account for them.

Once accessed, the platforms promote deposits as small as $10. From there, users can place bets for as little as 10 cents on live odds and statistics for a wide variety of sports. However, at a young age, they might not know how to make safe financial decisions with their sports betting or could develop an addiction, experts say.

The public’s perception of the ethics of sports betting has changed in the last few years because of the promotion and legalization of betting in most states, Daynard said. First, in 2018, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that states can legalize sports gambling. Then, Daynard said that states shifted toward legalizing it when the American Gaming Association, or AGA, made false representations to state legislatures exaggerating the threat posed by illegal offshore gambling operations.

Instead of telling lawmakers how gambling was going to addict millions of people, the AGA convinced them of the platforms’ revenue-generating potential, Daynard said. Following the lobbying, companies like DraftKings, FanDuel and MGM won over professional leagues, teams and ESPN with sponsorships.

“The minute those leagues started signing partnerships with the DraftKings people, and once they start going into the gambling side of things, it’s a whole different world,” said Patrick Jones, a postdoctoral teaching associate of communication studies at Northeastern. “That is a deep signal to society at large that this is okay.”

Jones believed the partnerships with leagues paired with massive advertising campaigns shifted the public’s perception of sports betting. When sports leagues embraced betting, the culture adjusted and became normalized by fans.

“These [sportsbook platforms] mean the opening of a multibillion-dollar new market. And certainly kids [in their late teens and early 20s], they’re the ones they want, right?” Jones said.

Jones added that the sportsbook companies are moving toward gamified betting. Since the new sports betting apps are designed with simple, easy-to-use mechanics, fans who access them can become attuned to the addictive model at a younger age.

“It’s a very obvious attempt to hybridize sports, to get conventional sports gambling with mobile gaming to attract a younger audience. Like, very obvious that that’s what that is for,” said Jones, who himself is a golf fan and occasionally uses DraftKings to bet on daily fantasy sports, an online game where players organize a team of real-life athletes and compete against others in a single day or week-long contest.

One app that has taken sports betting gamification to new heights is Fliff. Every day, users can log on and redeem coins and cash that can be wagered on a variety of live sports betting options.

Fliff is a legal “social sports betting” platform because of its sweepstakes model, a free-to-play and play-for-fun form of entertainment where no purchases are necessary to win. Users need to be at least 18 years old and verify their identity to move Fliff cash into a bank account but can start playing at any age by downloading the app and opening an account.

“I’d say it’s almost kid-friendly, like it tells you where everything is and it has, the cash on top and you can bet with coins just for fun,” said Pollock, who still uses Fliff as his primary sportsbook.

Ishaan Desai, a third-year computer engineering major, started betting last month when he turned 21. He bets on Fanatics Sportsbook and he is the legal age, but he noticed a shift in high school sports fans.

“I remember a couple of weeks ago in my hometown…there were these kids outside…they looked super young and they were talking about money lines so I went up to them and they said they were on Fliff,” Desai said. “So I said, ‘You guys can’t be a day above 17. You’re talking about money lines and spreads.’ I’d say what gambling companies are doing is working for sure.”

Desai said that the marketing around the gamified sports betting platforms combined with its increased accessibility grants access to younger fans. Since they are engaged in sports spectating, they can quickly become hooked on betting.

“It’s working,” added Desai. “Their marketing tools are strong, unlike in my case, I know the risks that come with it. I really analyzed it, so I made limits for myself on the apps. When you first make your account, they promote setting limits so that you don’t lose too much, but it’s not mandated.”

The platforms themselves have little regulation to how much you can bet. With the barriers to sports betting so low, Jones added that there needs to be tighter restrictions for accessing platforms like Fliff. He also said that lawmakers need to enforce that companies improve guardrails on their platforms to protect users from betting too much money.

“I think it should just be age-based,” Jones said. “I think it’s like you’re at a cap-bet if you’re under 21 or if you’re from like 21 to 25 years old, it could be 100 bucks a week.”

Daynard is now part of a group at the School of Law that is suing DraftKings over one of the company’s allegedly deceptive advertising campaigns geared toward young people. He believes that the companies might be targeting younger audiences because of their limited capacity to manage addiction which he said must stop.

“In terms of susceptibility, the part of the brain that’s most important for preventing addiction is the prefrontal [cortex], and it develops latest,” Daynard said. “So the [the prefrontal cortex] doesn’t fully develop until you are around 26 years old. That’s the part of the brain that says, ‘You know, this probably isn’t such a smart idea.’ You know, putting your career, your college education, your college funds and your whatever entirely at risk.”

In Jones’ Sports, Media, and Communication class, he spends a week discussing sports betting, its evolution and the marketing behind it. Through conversations with students, he noticed a change in perception about sports betting: Students do not see it as negatively as he saw it when he was their age.

“When I was a kid, I was taught gambling was wrong,” said Jones, who said he is afraid that the betting culture is evolving beyond repair while lawmakers refuse to step up. “Gambling specifically was immoral and unethical and evil-like, and that’s just so rapidly shifted now in the last seven years.”

These new norms around gambling, he said, “are not going away any time soon.”