By Molly Tankersley

The sleep-inducing term “net neutrality” instinctively makes me want to continue scrolling, close the tab or turn the page. The more I saw it in my news alerts, the stronger the will to ignore it, but I eventually learned the unfortunate truth: the implications of this discussion affect every Internet user out there.

In the media, net neutrality rules are depicted as prohibiting internet service providers (ISPs) from prioritizing different sites through the use of “fast lanes,” so that all sites are given equal service quality and speed.

Following a federal appeals court ruling in January that struck down net neutrality rules on the grounds that they wrongly treat broadband providers as traditional common carrier telecommunication services, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) is weighing its options on how to proceed.

Outside of the ISPs that will gain control as a result of the ruling to loosen net neutrality rules that require them to treat all Internet traffic equally, the flood of support for stricter protection of net neutrality has been uncharacteristically unanimous.

President Barack Obama released a statement this month advocating for the “strongest possible rules to protect net neutrality,” according to the White House. HBO news satire host John Oliver rallied his viewers to speak out in the defense of net neutrality. Soon after, the US public submitted almost 4 million comments to the FCC, enough to crash the FCC site, according to The Washington Post.

Google, Facebook and other major tech companies signed a letter asking the agency to stop blocks, discrimination and paid prioritization on the Internet.

Some web experts, however, think we may be missing the point.

“Most of the points of the debate are artificial, distracting and based on an incorrect mental model on how the internet works,” web developer Dave Taht told Wired on June 23.

One of the flaws in the net neutrality argument that Taht may be referring to is that the Internet isn’t neutral and hasn’t been for over a decade.

The Internet has been using fast lanes for some time now, and that is not necessarily the death sentence for online equality we may think it is.

As Robert McMillan explained in his article “What Everyone Gets Wrong in the Debate Over Net Neutrality” on Wired, fast lanes currently help companies to deliver the most popular web content at faster speeds, and reduce the amount of traffic that comes through their network. Any company that begins to generate the high level of traffic to require these services can arrange one of these lanes the same way Google or Netflix can.

It’s not as simple as instantly loading BuzzFeed articles for all, however, because the trouble with fast lanes lies in how they are used and, more importantly, who is controlling them.

The “who” is a handful of all-powerful service providers that hold a near monopoly on the service provider market. Companies like Comcast and Verizon have enough power and influence in the government to stand up against public opinion, the biggest tech companies and the president.

The real problem isn’t whether or not the FCC ruling goes through – it is that these companies have unchecked control over who has access to these fast lanes and how much it costs to access them.

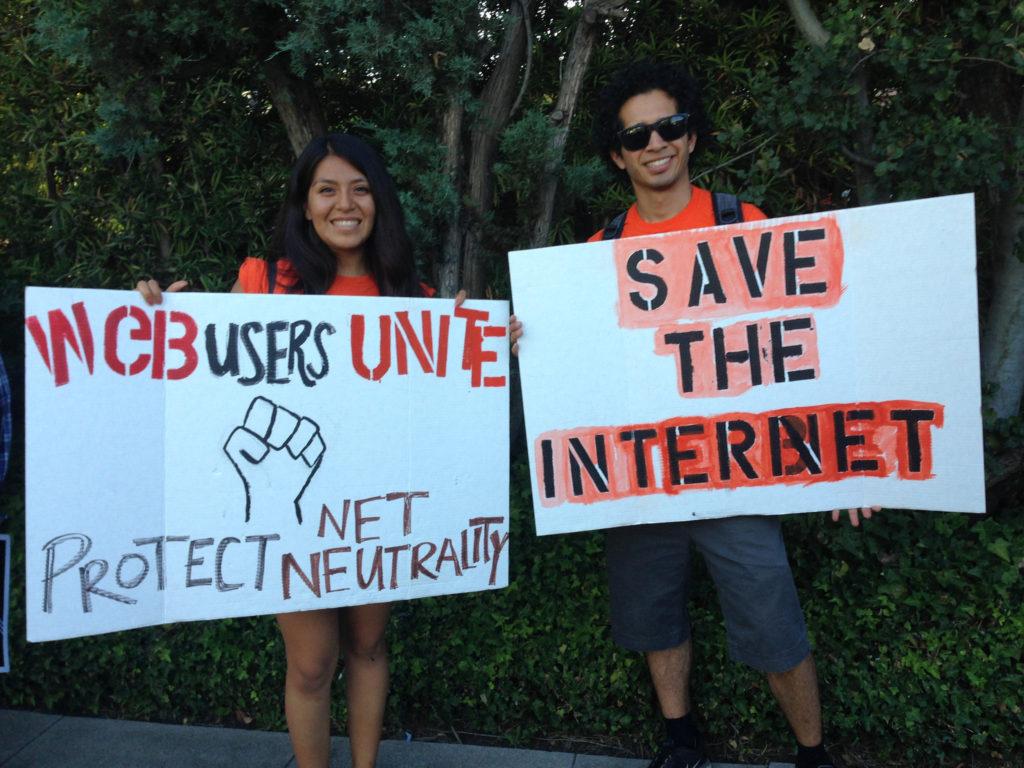

Photo courtesy Free Press, Creative Commons.