By Rowan Walrath, managing editor

Boston has long been known as a progressive city, but with its new status as the nation’s leader in income inequality, this may no longer be the case.

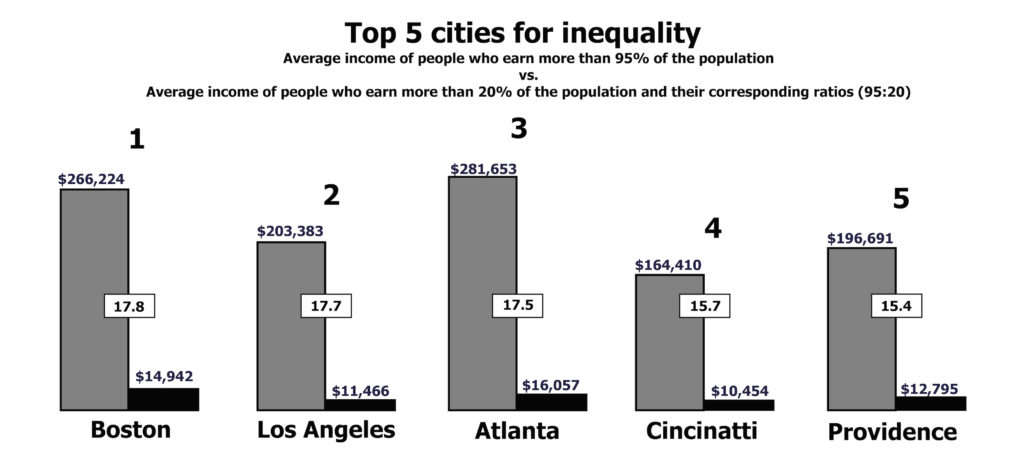

According to a Brookings Institution study, co-authored by Alan Berube and Natalie Holmes and released on Jan. 12, Boston is No. 1 in the country for income inequality. Nearby metro areas Greater New York and New Haven, Conn. also landed in the top 10. On the West Coast, both the San Francisco and Los Angeles metro areas also exhibited high levels of income inequality. So did the southern metro areas of New Orleans, Miami and Houston, the former two largely due to the low incomes earned by their poorer households – below $20,000 in both cases.

Oscar Brookins, an associate professor of economics at Northeastern, shed some light on what the numbers mean.

“The point the numbers show is that it is a consistent story across the world and the country… over time, the upper-income people are increasing their income relative to the bottom half, in this case, in the bottom 20 percent,” Brookins said. “When you look at the ratios, Boston is at the top. There are three decimal places that separate Boston from the third place, so those are essentially the same. When you go from 17 to 15, then there is a much greater difference.”

According to the report, local inequality has a number of effects. It may diminish the ability of schools to maintain mixed-income populations, which produce better outcomes for low-income students. It may narrow the tax base from which municipalities raise the revenues needed to provide essential public services while weakening the collective political will to make those investments. And local inequality may raise the price of private-sector goods and services for poor households, making it even more difficult for them to get by on their limited incomes.

Hamza Maanane, a sophomore English major at Northeastern, spoke on the effect this income gap has on education.

“It seems backward that a city who is so focused on education has such a discrepancy because it seems the goal of education is to bring those who are low upward.”

However, William Dickens, university distinguished professor and chair of the department of economics at Northeastern, said that more analytics are needed before the report can amount to much.

“In general, I don’t think we learn much from this kind of data analysis, which is done without any theoretical foundation,” Dickens said in an email to The News. “What of relevance do we learn if we know that Boston has extreme income inequality that is mainly due to its large student population? One needs to approach the issue of income inequality with an eye toward identifying the causes and consequences and how to deal with the negative consequences. Most work by economists deals with these sorts of issues.”

According to Brookins, these numbers may present a bleak future for the City of Boston.

“Those are huge numbers and huge differences in the bigger picture it can assure what we have observed in the world that the rich get richer and the poor get poorer… can this society sustain if those numbers get worse?” Brookins said. “If we get to a ratio of 20 or so, I don’t think society would be sustainable.”

Tyler Morse, a student in the College of Professional Studies at Northeastern, has his own theory about the reason for those numbers.

“It’s the influx of foreign money mixed with the historical and commercial money that’s already in Boston,” Morse said. “There’s a reason people say Boston is blue collar, but there is more to it.”

Morse believes that a lack of new money in the Greater Boston Area is largely to blame for the city’s income inequality issue.

“It’s historical wealth from historical families of Boston, too,” Morse said. “It’s their legacies. But I think some of the inequality comes directly from wealthy foreigners, too. Both of those amounts of wealth just throw the whole balance.”

The gap is not merely an economic problem, Brookins pointed out. As it grows, it seeps into the sociopolitical sector.

“It has only been around for a few years that economists have begun to think about this,” Brookins said. “Now, it is virtually on everybody’s radar, given that this gap is widening. At what point does it reach a proportion that it is inoperable – that is, disposes a social and political problem?… Certainly, that number is heading in the wrong direction.”

News graphic by Robert Smith