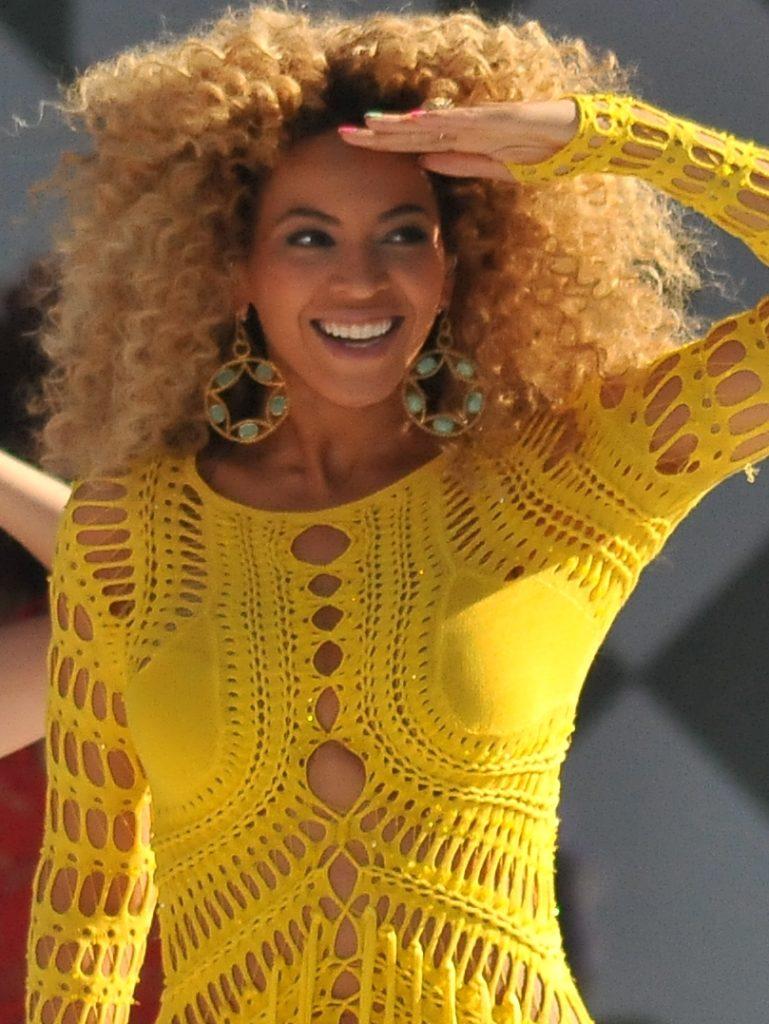

Sunday’s Super Bowl, a hard-fought 24-10 victory for the Denver Broncos, was, by many accounts, not the most compelling football game in recent memory. Aside from mediocre play, the event was dominated by its halftime show. An aging Coldplay, peddling a multicolored message of peace, dusted off a collection of classics; Super Bowl regular Bruno Mars delivered a rendition of his hit “Uptown Funk;” and Beyoncé, leading a crew of backup dancers whose movements and clothing alternately evoked Michael Jackson and Malcolm X, performed an ode to blackness in “Formation,” a song whose politically charged music video had debuted 24 hours earlier.

Reaction to “Formation” came swift and strong. In the eyes of some, America’s favorite pop queen had unleashed a timely progressive commentary on race and oppression. Others who saw a threat or a provocation accused the singer of “race-baiting” and politicizing an apolitical event. This group includes former New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani, who appeared Monday on Fox News to say, “I thought it was really outrageous that she used it as a platform to attack police officers, who are the people who protect her and protect us and keep us alive.”

Giuliani’s fearful and fear-mongering criticism was off-base. He’s wrong about groups like Black Lives Matter who protest police brutality and the killing of unarmed African-Americans: attacking police officers isn’t on their agenda. Condemning police brutality is not condemning the police. Black Lives Matter is followed by an implicit “just as much as white lives,” not by an “instead of white lives.”

Moreover, “Formation” is about more than the explicit politics of police-community relations. It’s about love. It’s about pride. It’s about black self-love and black pride, specifically. Yes, it’s also defiance to discrimination, pushback to hate and an indictment of white supremacy and white privilege, but its core is affirmation. At the Super Bowl, Beyoncé sang about blackness for herself and for southern black Americans, but she didn’t demand that anyone else listen. In doing so, she succeeded in crafting a message.

Some of the discussion concerning “Formation” mirrors that around another song released two weeks earlier: “White Privilege II,” penned and performed by Macklemore. The work is a nine-minute–long description of his struggles with being a white ally, with being a white rap artist and with trying – and sometimes failing – to join a culture he profits from without appropriating it. To be clear, “White Privilege II” is imperfect, and Macklemore doesn’t deserve a pass for appropriation just because he has self-awareness, but his attempt to grapple with the steps that come after acknowledging privilege are worthwhile, no matter how his career may benefit.

“White Privilege II” is a window into the uncomfortable act of attempting to step out of a place of comfort a white man hasn’t earned. “Formation” is a power hymn asserting the right to feel comfortably black when this country so often penalizes such feelings. “Formation” is an empowerment anthem; “White Privilege II” is a spoken-word monologue seeking, desperately yet (probably) earnestly, to be a dialogue.

Both messages are part of a larger conversation that Americans, and particularly young Americans, should be having. Many college students pride themselves on either being colorblind and universal or hyper-aware of the privileges afforded them and the obstacles others face due to race, gender, class, etc. For the first time, a majority of all Americans agree both that there’s racial inequality in the US and that they want to do something about it, according to a new study conducted by the Kellogg Foundation and the Northeastern School of Journalism.

Good intentions, it seems, abound. What we believe, and what both of these songs consciously advance, is that such intentions must not give way to complacency. Agreeing there’s a problem is the first step toward solving it, nothing more. Thinking (or writing) about Beyoncé and Macklemore and race is another step; what must come next is engagement, dialogue and action.

Photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons