Roxbury residents face gentrification

January 18, 2018

Jordana Soliel-Montiero stands on Columbus Avenue in Roxbury and photographs a dynamic, changing neighborhood. She captures old buildings being torn down as the steel frames of others rise. She captures workers passing by in their bright neon vests, which stand out against drab dirt mounds. She captures tall buildings that loom over the neighborhood.

Soliel-Montiero’s pictures are not just of busy construction scenes and gleaming new buildings. They are of a neighborhood — her neighborhood — fading away. Once a vibrant community filled with black residents, including civil rights activist Malcolm X, Roxbury has become a commercial hub: Urban planners and developers are redefining the neighborhood as a hotspot for urban renewal. Soliel-Montiero is determined to document how Roxbury is becoming a “dream deferred,” — the phrase Langston Hughes used to describe Harlem in his poem named for the city. Roxbury, like Harlem, is fading away.

A HISTORIC NEIGHBORHOOD

The historical significance that made Roxbury so uniquely Roxbury is becoming irrelevant. Residents used to be proud of Roxbury’s past — though tumultuous, it was interconnected with cultural significance. From its settlement in 1630 by English Puritans to housing Malcolm X for seven years, residents fondly remember its history as they gaze upon the streets.

Some parts of Roxbury’s past are not remembered as fondly. According to the Roxbury Historical Society, Roxbury’s demographic became increasingly African-American during the 1960s and 1970s. City planners and developers viewed the area as run-down and dangerous. Urban renewal efforts, like the planned construction of the Southwest Expressway, a 12-lane highway that would have cut right through residential Roxbury, troubled residents, said Chuck Turner, former Boston city councillor representing Roxbury’s District 7. The Boston Planning and Development Agency, or BPDA, dramatically changed Roxbury with two initiatives: the Washington Park Urban Renewal Program and the Campus High Urban Renewal Program. Many homes, businesses, schools and churches were torn down and hundreds of residents were displaced as a result.

Roxbury continued changing drastically in the 1980s and 1990s. The Boston Redevelopment Agency focused on redeveloping damaged areas of the neighborhood left behind by civil rights riots of the late 1960s. Elise Sutherland, a long-time Roxbury resident, saw Roxbury shift from a worn out, dirty, overpopulated area to a cleaner neighborhood with new shopping and entertainment centers, gleaming municipal buildings and high-rise condo apartments. Empty lots, overgrown with weeds and littered with beer bottles, were transformed into schools, art studios and cafés. Crime rates dropped. From the outside, it seemed Roxbury was finally changing for the better after a long history of strife and turmoil.

The harsh reality, though, was that this urban renewal was not entirely beneficial to the area’s historical and cultural significance. Sutherland said the change was not something residents had driven. Rather, it was external development that changed the face of the neighborhood and hurt residents.

Although there were finally enough places to shop for groceries in the neighborhood, residents found that the prices were too high. This and rising property values costs were among many new struggles the changes brought to residents. Sutherland and Soliel-Montiero’s families were two of them.

Soliel-Montiero calls herself a “Roxbury kid,” as she grew up in Roxbury and has been living in the neighborhood for more than 30 years. Her best friend used to live across the street from her, and her classmates and other friends lived close by as well. However, one by one they left the neighborhood.

As the transformation continues in Roxbury, Soliel-Montiero feels it is her duty as a photographer to document it.

Sutherland, too, watched her neighborhood drastically change, and had to personally watch all her childhood friends move away.

“When I was a kid, I could walk down the street and say hi to everyone, because I knew everyone,” Sutherland said. “We were all proud to live in the same community together. Now, I hardly know anyone. They were all pushed out.”

On Tremont Street, old buildings rest, dusty with age and faded “closed” signs hanging in the windows. A block over, on Columbus Avenue, construction workers balance on steel beams maneuvering tools, sending showers of sparks five floors below. Countless college students hurry along the street every day, trying not to be late to class or returning to the comfort of their dorms, several of which line the street.The Roxbury Soliel-Montiero has known for her whole life is almost unrecognizable, she says, and soon the transformation might be complete.

FACING GENTRIFICATION

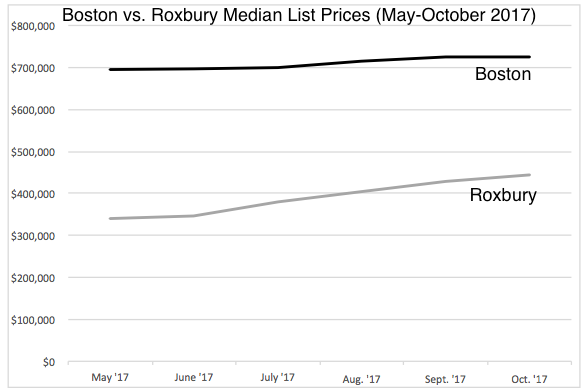

The Imagine Boston 2030 Report — a plan for the future of Boston — reflects this change in data. The report says housing prices in Roxbury rose nearly 70 percent between 2010 and 2015, while housing prices in Boston as a whole only increased by 36 percent. Data from Zillow said from May to October 2017, the median list housing prices for Boston went up $30,000, a 4.3 percent increase, while the average rent prices for Roxbury went up $104,000, a 34.2 percent increase.

Roxbury is not the only neighborhood in the United States experiencing this detrimental sort of urban renewal, or gentrification. A 2014 Mic article placed Boston at the top of the list of gentrifying U.S. cities, while Seattle, New York City and San Francisco came in second, third and fourth respectively. Washington, D.C., Atlanta and Chicago had similar statistics.

The discourse and rhetoric surrounding gentrification has left citizens and public officials divided. Many urban developers and planners, like those at the BPDA, have expressed that urban renewal is beneficial to older neighborhoods.

“The redevelopment of older and less renovated neighborhoods like Roxbury creates both affordable housing spaces and makes the neighborhoods look more welcoming,” said Courtney Sharpe, a BPDA board member, at a Roxbury Strategic Master Plan meeting in March 2017.

Similarly, Gerald Autler, the BPDA senior project manager and planner, said although Roxbury residents may have to relocate to new housing situations, he and the BPDA anticipate that projects should provide ample affordable housing for those who may need it. This includes Tremont Crossing, a building project slated to have nearly 2 million square feet of office, retail and residential spaces.

Many Roxbury residents disagree with developers like Sharp and Autler, who frame redevelopment as a positive for Roxbury.

Urban affairs scholar Thomas Vicino, chair of the political science department at Northeastern University, noted in a Dec. 5 “Perspectives on Gentrification” panel at Northeastern that the identities of neighborhoods, no matter how deeply rooted in historical and cultural significance, change drastically when they encounter persistent urban renewal efforts. Vicino also said as the rent and property values of a neighborhood go up, local and state taxes will also increase.

“If you take Roxbury for example, a lot of young white folks like college students are moving in,” he said during the panel. “They’re not going to want to go to an old diner, they’ll want a trendy vegan café. And existing businesses will either have to adapt to that, or close and let someone else do the job.”

To Soliel-Montiero, Roxbury was Roxbury because of that certain diner that was so much like her mother’s homemade soul food, or that one jazz club she went to with her friends on weekends. Now, they’re replaced by a vegan restaurant and a bar, both hotspots for college students, who represent a rising demographic in the neighborhood. Residents are bidding farewell to the Roxbury they have known and loved since they were born.

“I’m no longer comfortable in my own neighborhood,” Sutherland said. “The friendly faces I always said hello to are long gone. Now, I just go about my business, and so does everyone else. Roxbury is not a community anymore.”

PUSHED OUT

Armani White, a longtime resident of Roxbury and a community organizer for Reclaim Roxbury, a grassroots organization that seeks to empower Roxbury residents, said he and his parents have felt pressured over the last five years to move out of their home. His parents bought their house, which he currently lives in, for less than $30,000 in the 1980s.

White said that his parents get offers almost every month that are close to a million dollars. His parents tell developers the same thing every time, that they’re not interested, and that they don’t intend to sell it anytime soon.

This incessant communication, said White, has begun to make him feel unwelcome in his own neighborhood.

“It’s like I’m being incentivized to get out of my home,” White said.

White says he is just one of many Roxbury residents who are constantly told that they should move out of their homes.

Planners and developers like Sharpe and Autler do have a plan for residents who are requested to move out of their homes. Autler said developers set aside a certain number of housing units in new complexes for families who are displaced. These are sold or rented under market value. Nonetheless, the discount often is nowhere near enough.

Unlike White and his family, some families cannot afford to reject constant offers for their property. According to data from the U.S. Census Bureau, the median household income for Roxbury is $34,374, while the median household income for Boston is $54,485. Additionally, the unemployment rate for Roxbury is 10.7 percent compared to 6.8 percent for Boston. As property prices in Roxbury steadily grow, so do real estate taxes and rent prices.

Even residents who already own homes are not immune to this change. Many residents are unable to keep up and have to resort to alternative housing situations.

Jeff Rogers, a longtime Roxbury resident, has seen many of his fellow residents leave. At the “Perspectives on Gentrification” panel, he noted that as soon as residents move out, construction workers will likely come in, knock down walls and try to build as many housing units as possible. He’s seen workers convert beautiful Victorian or carriage-style homes into multiple condos that can net well over $3,000 monthly.

To residents, it is perhaps the most heart-wrenching way to bid farewell to their neighborhood. White said they are “forced to be part of a system of developers and planners who are changing Roxbury, perhaps permanently.”

ROXBURY RESPONDS

Several organizations are rallying resistance efforts, including Reclaim Roxbury, Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative, City Life Vida Urbana and Right to the City. All of these organizations seek to educate and inform residents on measures they can take to voice their concerns. Activists urge community members to attend public meetings about building projects.

Though community organizers and residents work to ensure fairness, sometimes things do fall through the cracks. For example, Northeastern, which borders Roxbury on Columbus Avenue, is currently building a 22-story dorm on Burke Street. It is a few blocks from another 22-story dorm, International Village. When they announced plans for the dorm to the community, contractors said it would be an eight-story building. Tito Jackson, former city councilor (D-7) and 2017 mayoral candidate, was surprised at Northeastern and the contractor for reneging on their agreement with the community.

“Northeastern spent a year and a half with us doing an Institutional Master Plan, and they turned around and betrayed the community after that,” Jackson said in an interview with The News in September 2016. “I have an issue with President Aoun and the administration at Northeastern [for] showing a complete and utter disregard and disrespect for the agreement they spent a year and a half crafting with the community.”

Residents may try to voice their struggles, but it seems as if developers get to do what they want regardless of community input. Northeastern is just one developer among many that are drastically changing Roxbury. More tall buildings will cast their shadows over the neighborhood soon.

Yet there is still beauty found in what remains, still hope for Roxbury. Residents say that there are still things people can do to save the historic buildings and keep it from disappearing altogether.

Residents encourage students who live in Roxbury and other neighborhoods off campus to appreciate and respect the community around them. Sutherland suggested students focus on community building efforts, which could range from just saying “hi” when they see their neighbors to tutoring elementary school children. Sutherland also urged students to come to community meetings about building projects and voice their input, as they are literally Roxbury residents too. Other residents like White encouraged students to learn about and appreciate Roxbury’s unique and rich history.

“Don’t stay hung up on the stereotypes about Roxbury you always hear, because I can tell you that the Roxbury I have always known is just as beautiful and special as any other neighborhood in Boston,” White said. “Learn to acknowledge and appreciate that beauty.”

Soliel-Montiero, as she held her camera in her hand and snapped away at bundled-up pedestrians and old, quaint buildings, was doing just that: trying to preserve and celebrate what remains of Roxbury, the Roxbury she had known for more than 25 years.

“I want everyone to see what Roxbury really is like, and I know that if I take the right pictures, it will help in inspiring people to make Roxbury what it once was again,” she said. “There’s still hope for Roxbury, my Roxbury.”

Updated on Jan. 19 at 10:45 p.m. to clarify that Thomas Vicino’s quotes were from a Dec. 5 “Perspectives on Gentrification” panel.

Updated on Jan. 20 at 2:27 p.m. to clarify that Jeff Roger’s quotes were from a Dec. 5 “Perspectives on Gentrification” panel.

Updated on Jan. 20 at 10:22 p.m. to clarify that Courtney Sharpe and Gerald Autler’s quotes were from a March BPDA board and community meeting.

Updated on Jan. 24 at 06:15 p.m. to correct that White’s parents bought their home in the 80s, and that his parents get the offers for the home.