Column: Black history is everyone’s history

Photo Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

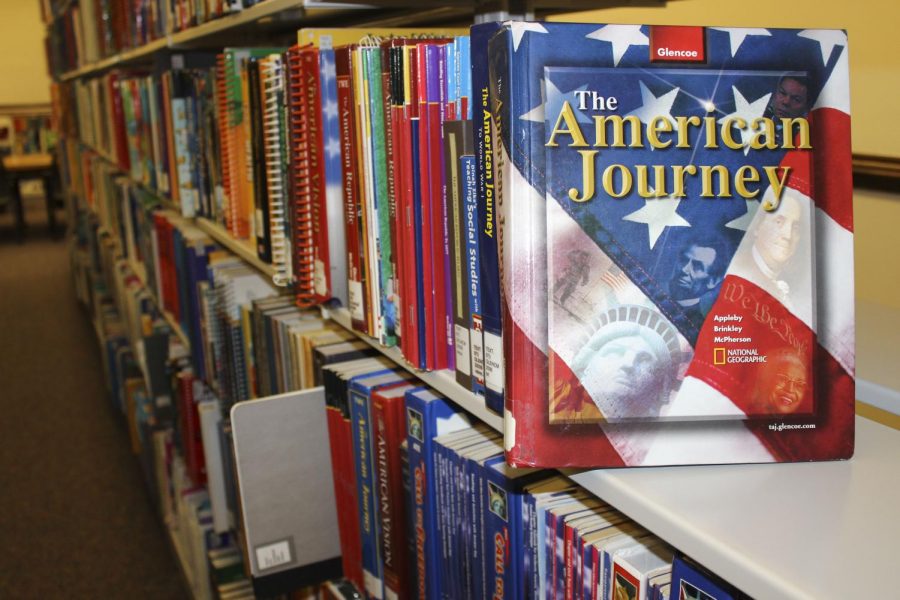

We must make an effort to learn about the true diversity within American history.

February 27, 2019

At Northeastern, 6 percent of students are African American, 8 percent are Hispanic, 16 percent are Asian American and 1 percent is Native American. What do all of these groups have in common besides being minorities here? They all have heritage months. Why?

American history is notorious for neglecting the history, life stories and accomplishments of marginalized communities that helped build this country. Therefore, minorities have heritage months to celebrate their portion of history frequently left out, especially in the classroom. The College Board currently offers three Advanced Placement history exams: European history, United States history and world history. Why does European history get its own course while all others are distributed within world history?

Not only do curricula neglect non-Eurocentric content, but they also skew and misrepresent the experiences of minority communities. As Black History Month winds down, it is important to address why this month is so important – and not just to Black people.

Although Black History Month specifies Black history, it is really a month to acknowledge what should be generally seen as American history. That means not only commemorating Black people within forgotten American history, but also the white people in positions of power that perpetuate inequality. Black History Month allows white and non-Black people of color to reflect on their privilege.

School curricula are improving, but Black history is often only taught during February. This trend gives the impression that Black history is unimportant the other 337 days of the year. As with any heritage, it is most impactful when its history is considered on a regular basis. Teaching history is crucial to how we evolve from our past, and students are more likely to recognize injustices if reminded of their origins.

The study of slavery explains many present-day issues the United States still battles. Redlining, for example, was a discriminatory practice that allowed mortgage lenders to section off neighborhoods with red lines so they could reject housing loans to credit-worthy people. The effects of this continue to devastate Black communities today. If such history is not taught in our classrooms, how can we expect the next generation to correct the errors of the past?

More schools should adopt requirements like those within Northeastern’s history department, which require students to complete one course from the category of “History Outside the United States and Europe” to earn a history degree. If every department integrated a non-Eurocentric history requirement, students would inherently be more aware of issues within marginalized communities.

It is not Black people’s responsibility to correct their peers’ and professors’ microaggressions and at times, overt racism. We must all learn about the roles marginalized groups played in American history to promote an environment conducive to optimal learning. Black history is especially important at an institution that boasts diversity, but lacks Black students; when questions about slavery or racism arise, professors shouldn’t look to the two or three Black students in predominantly white classes.

As a Black student at Northeastern, I rarely come across Black professors who understand my experience as a minority at a predominantly white institution. If a professor uses their position of power to reinforce the importance of Black history, not only is my college experience enriched, but so are the lives of my white peers.

If you are white and reading this, how many times have you been the only one in your classroom? The reality is, probably never in your academic career. The uncomfortable feeling of isolation Black students feel every day could be alleviated by something as simple as seeing our history normalized.

So, participate in Black History Month. Make an effort to learn about the true diversity within American history regularly, because that can only have positive effects on our society.

As Chimamanda Adichie says in her famous Ted Talk, “The Danger of a Single Story” – “Stories matter. Many stories matter. Stories have been used to dispossess and to malign, but stories can also be used to empower and to humanize. Stories can break the dignity of a people, but stories can also repair that broken dignity.”