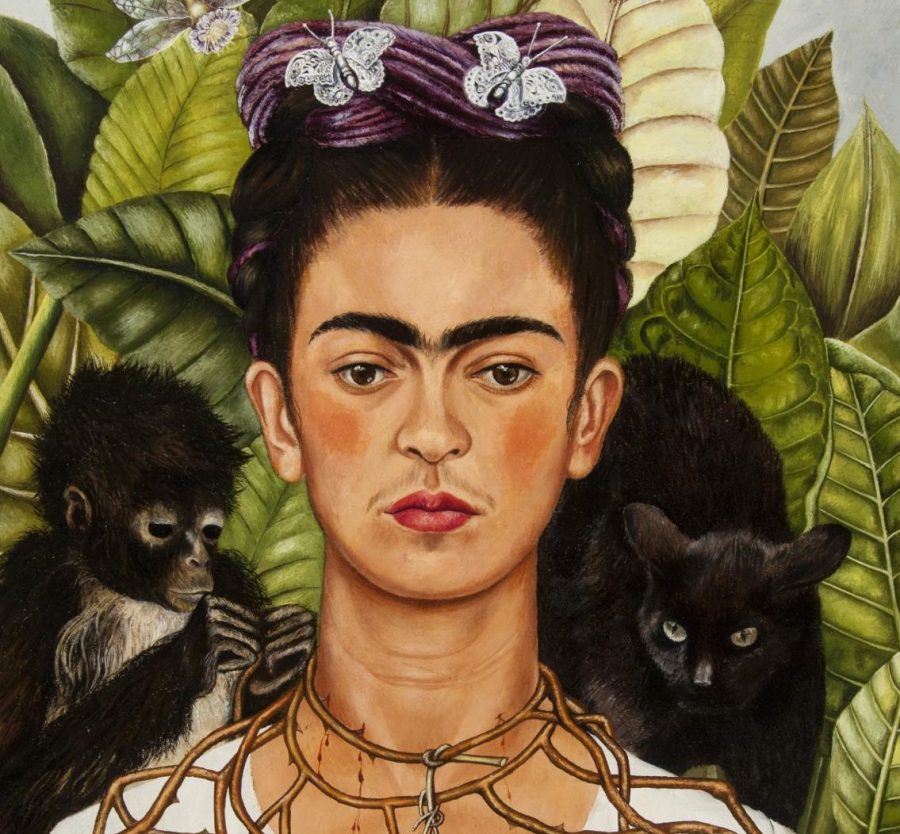

MFA exhibits ‘Frida Kahlo and Arte Popular’

Photo courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

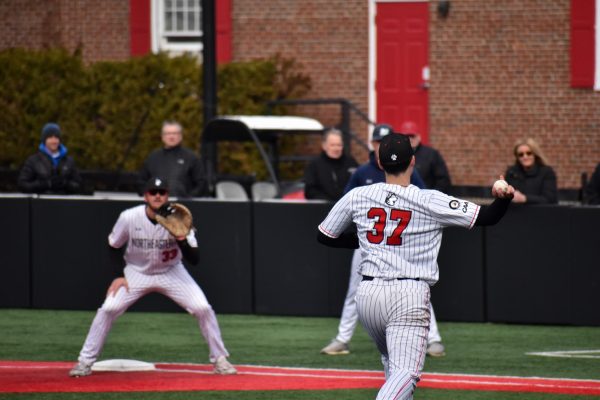

Mexican artist Frida Kahlo’s 1940 “Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird” will be on display at the MFA through June 16. Nickolas Muray Collection of Modern Mexican Art, Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin. © 2018 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

February 27, 2019

Mexican self-taught artist Frida Kahlo’s paintings give insight into her tortured mind at the Museum of Fine Arts, or MFA, which previewed its first exhibition of Kahlo’s work on Friday.

The exhibition fills two rooms and was curated by Layla Bermeo. It includes decorated ceramics, embroidered textiles, children’s toys, devotional retablo paintings, Kahlo’s iconic self-portraits and photos for context and storytelling.

Bermeo guided visitors on a tour, telling stories of the “ambitious” and “ever-evolving painter” while explaining the stories behind some of Kahlo’s notable creations and Bermeo’s thought process in curating the exhibit of rare pieces.

Upon entering the exhibit, visitors are welcomed with a decorative paper-mache skeleton, a symbol for the Mexican holiday “Día de los Muertos,” or Day of the Dead. A pair of large ceramic pots painted in floral detail stand in the center of the room, as representative examples of the kind of “arte popular” that she would have collected, and behind that, two of Kahlo’s self-portraits.

Throughout her life, Kahlo collected traditional Mexican folk art — “arte popular” — and drew inspiration from their political significance after the Mexican Revolution. Politicians and artists tried to construct a new narrative for Mexico that spoke to unification.

Her paintings, most notably her self-portraits, represent questions of identity, postcolonialism, gender, class and race in Mexican society, Bermeo said.

One portrait, “Dos Mujeres,” represents an early milestone in her painting career, while “Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird” was painted during the peak of her career. The two pieces, displayed on opposite ends of a wall in the exhibition, highlight her progress as a painter.

Arte popular influenced Kahlo’s entire career, from her early portraits to her late still-life paintings. Kahlo came to represent a purely Mexican aesthetic, but her inspirations and influences were more complex, Bermeo said.

Kahlo began seriously making art when she was bedridden after being hit by a trolley. Her life was followed by more disabilities and childhood polio. She made a lot of artwork while she was in bed, where she propped up a canvas above her and enveloped herself in her painting. Her tumultuous marriage to muralist Diego Rivera, her politics and her pain — both internal and external — gave her inspiration.

“She is inspired by folk art, but she is not a folk artist,” Bermeo said.

A selection of Kahlo’s pieces were loaned by the Museum of Modern Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin.

One of the two rooms showcases Frida’s emblematic “Tehuana” dress, made in the 1930s and 40s in Tehuantepec, Mexico. Kahlo was a member of the middle class from an educated family, and promoted these garments as a show of cultural solidarity.

Photographs of Kahlo at different stages of her life and with artists she collaborated with are also part of the exhibition. Bermeo’s purpose for this was to add context and history of the artist.

“I tried to be sensitive of the way works [about] Kahlo tend to replace the works by her,” Bermeo said. “The photographs that we included hopefully relate more to the dialogue about her and her work.”

Alongside the main exhibit is “El baño de Frida (Frida’s bathroom),” an intimate collection of photos shot by Graciela Iturbide taken in Kahlo’s bathroom in Mexico City. “Folk Art of the Americas,” a collection of paintings, ceramics and sculptures by various artists, is showcased as well.

The “Frida Kahlo and Arte Popular” exhibition will be open to the public through June 16.