On-campus wind tunnels: “delightful” or dangerous?

Kaitlyn Moleti, a first-year behavioral neuroscience major and East Village resident, said she has to walk through the wind tunnel on St. Botolph Street every day.

September 17, 2019

Naturally occurring wind tunnels on Northeastern’s campus regularly blast students and professors with gusts of great size.

Architecture on campus transforms wind patterns and weather into phenomena called “wind tunnels.” These wind tunnels have become fixtures on campus, affecting many students daily on their commute to class or home.

“I hate that we live right by a wind tunnel,” said Ana Sobrino, a first-year bioengineering major. Sobrino said she is regularly bothered by strong winds outside East Village.

David Fannon, a professor in the School of Architecture and the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, said there is an explanation for how wind tunnels are created — the Venturi effect.

“What you see if you have a city or campus, say with a bunch of buildings and a big field of wind moving through it and there’s a narrow spot, that wind is going to be constricted,” he said.

As the wind field is constricted, the Venturi effect causes wind speed to increase and pressure to drop, resulting in the formidable gusts those who trek across Northeastern’s campus are familiar with.

Two locations in particular are hotspots for these wind tunnels. One notable location is along St. Botolph Street, between the buildings that line the road leading to East Village. Another runs between the bottom of Ruggles Station’s stone staircase and the base of International Village.

Fannon said the relatively tall statures of these two residence halls, as compared with the rest of the buildings on Northeastern’s campus, further exacerbate the wind’s effects. He said both spots are susceptible to the Venturi effect, as they feature landscapes where a larger area is suddenly narrowed to a smaller space by the fixed positions of surrounding buildings.

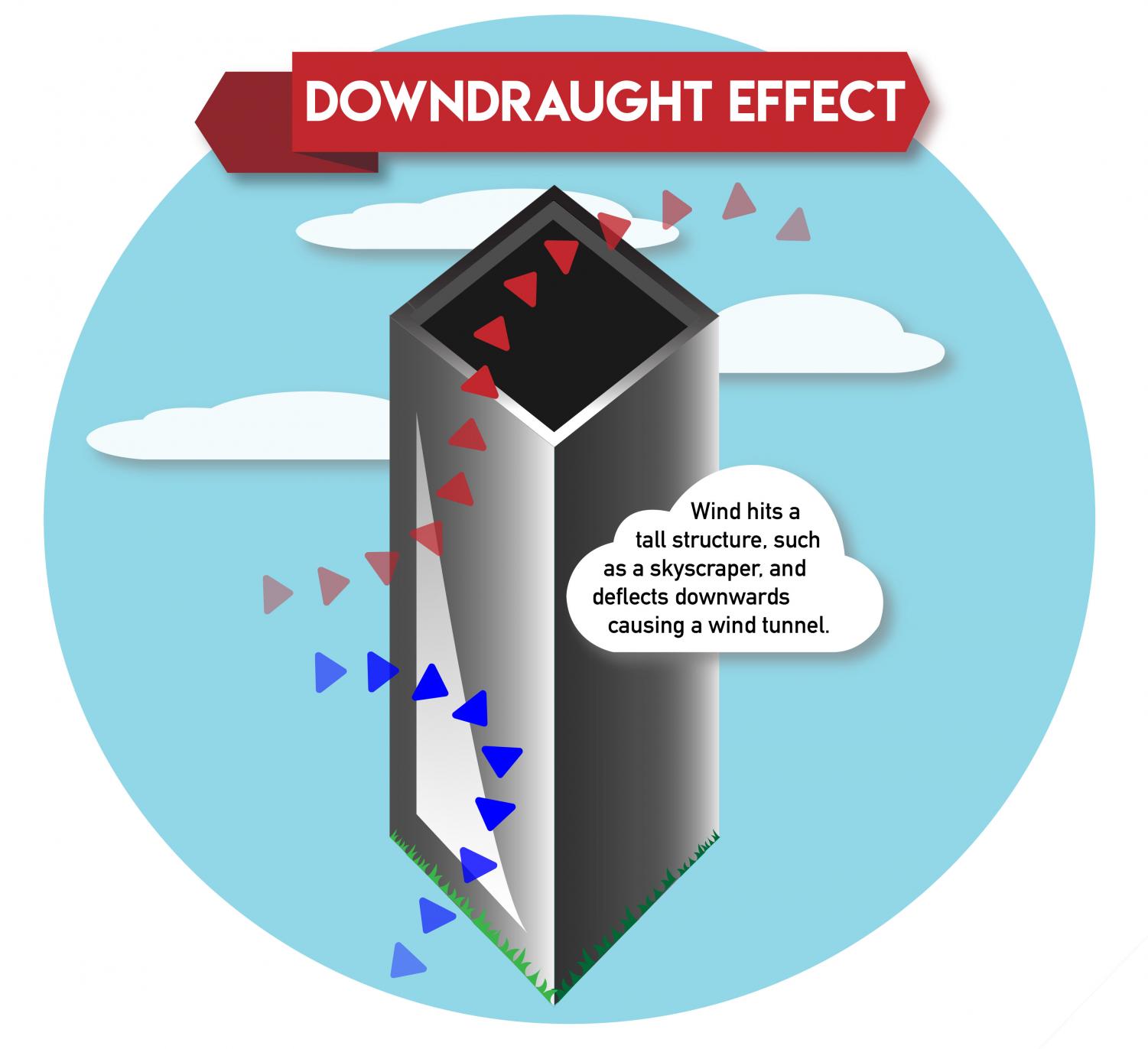

To begin with, wind moves faster at a higher altitude. When the wind hits a tall building, a portion of it passes over, while the remainder curves down the side of the building in what’s called a downdraft. When the downdraft reaches the ground, it rolls over on itself, creating a turbulence-like effect.

“That coupled with the Venturi effect in the air moving past the buildings can often increase the wind speed,” Fannon said.

Though not imminently dangerous in favorable weather, students said the wind tunnels pose an inconvenience to them.

“I think it really changes your opinion of the day’s weather, because it’s very chilly compared to the rest of the day,” said Tabetha Rowlands, a first-year environmental engineering major and an East Village resident.

Students said the tunnels’ effects seem more hazardous during inclement weather. Kaitlyn Moleti, a first-year behavioral neuroscience major, said she was walking to her dorm in East Village on a rainy Wednesday morning when a sizable gust of wind caused her umbrella to invert.

Ananya Sankar, a first-year journalism major and International Village resident, said she is worried about the wind tunnels in the winter. “I’m concerned about what’s going to happen in the colder months, especially when it starts snowing because that could be potentially dangerous and a health hazard,” she said.

In terms of whether the university could have laid out the campus to prevent these gusty spots from popping up, Fannon said it’s hard to know in advance what effect a building is going to have. “You could change everything about the flow patterns in a city by changing one or two buildings,” he said.

He said there are, however, a few measures that can be taken to somewhat reduce the tunnels’ bothersome effects, such as walking close to a building’s wall, near the outer edges of a wind tunnel, to get some respite from the strongest wind.

“We usually find that the wind speed will be lowest closest to the building because buildings are rough,” Fannon said.

He also discouraged pedestrians from walking backwards to try to combat the wind, saying it’s “not a good idea.”

Fannon also suggested students travel in packs. “If you have a bunch of people, individuals on the outside will kind of break the wind and people on the inside will be protected.”

Whether these wind tunnels are a nuisance or something to be celebrated is ultimately up to individual interpretation.

Fannon acknowledged this duality, saying, “I guess there’s two ways to think about it. You can say, well, you know, it’s a problem because there’s these elevated wind speeds. But you could also say it kind of makes these unique and delightful moments that people can talk about and remember.”