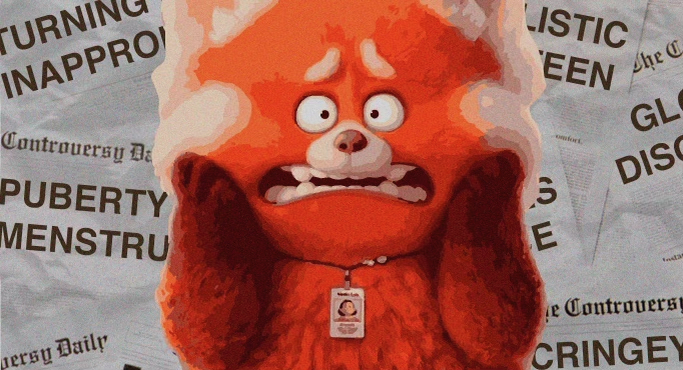

Column: ‘Turning Red’ criticized for themes of growing up

“Turning Red” takes on young girlhood and coming of age, but some critics took issue with the film’s novel themes.

April 3, 2022

Disney and Pixar’s latest film “Turning Red” follows 13-year-old Meilin Lee and her newfound tendency to transform into a giant, red panda when faced with intense emotions. The film explores Chinese heritage, generational trauma and coming of age, but its portrayal of young teenage girl experiences has some critics up in arms.

Somehow, a quirky story about the chaos of youth has now become Pixar’s “most controversial film.” Upset by the film’s mention of menstruation, romantic crushes and autonomy, critics — particularly parents — claim that “Turning Red” depicts teenagers unrealistically and is inappropriate for child audiences.

It is no secret that Lee is unapologetically crazy about boys: she routinely gawks at boys in the school hallway, doodles in her notebook about her crushes and has an obsession with the boy band 4*Town. And as a result, reviewers shamed Lee for being “too cringey” and “annoying.”

But at the age of 13, who wasn’t?

In support of “Turning Red,” the hashtag #at13 trended on Twitter as users shared personal stories about the fictional characters they fell in love with and the embarrassing things they were drawing, reading and writing at 13 years old. After all, it is only typical of teenagers to behave in their youthful ways — Lee isn’t alone and shouldn’t be shamed for acting her age.

Contrary to what critics say, Lee’s interest in 4*Town is very realistic. Many teenage girls had romantic crushes and were passionate fangirls of male celebrities such as One Direction, Justin Bieber and Edward Cullen of the “Twilight” series. This, of course, meant lots of fantasizing and swooning, just like Lee.

Reviewers deemed Lee’s harmless pining as an improper portrayal of sexuality. But adolescent sexuality is normal and “Turning Red” explores it without actually sexualizing children. Usually, fictional adolescents are either oversexualized or express no sexuality at all. For instance, Betty Cooper, a 16 or 17 year-old character from “Riverdale” played by 25-year-old actress Lili Reinhart was shown strip teasing and pole dancing in front of a crowd of adults. On the other hand, the concept of sexuality is entirely nonexistent in most Disney movies with teenage characters.

Without including any mentions of sex or anything inherently sexual, “Turning Red” accurately depicts the often relatable, awkward and weird feelings that come with teen sexuality and coming of age.

While many films in the media industry tend to mock the interests of teen girls, “Turning Red” fully embraces Lee’s interests. Hollywood has a history of devaluing the interests of teen girls, like the color pink or shopping, by reducing them to a negative narrative of passivity and vacuity.

Characters with these stereotypically “girly” interests are depicted as unintelligent and shallow, serving solely as secondary characters meant to be compared with the main protagonist. Take, for example, Sharpay Evans and Gabriella Montez from “High School Musical.” Portrayed as dumb and vain, the film mocked Evans for loving dazzling pink and designer branded things, as well as for her confidence. In comparison, the film portrayed Montez as the intelligent, respectable and strong heroine.

When the media repeatedly demonizes certain hobbies in a condescending light, young audiences who are still developing their own personality and interests may begin to reject what they’re drawn to in fear of becoming the characters they see portrayed in the media.

Yet in the case of “Turning Red,” Lee’s shameless pink-wearing, mermen-drawing and 4*Town-singing tendencies are a loving and playful part of her charm. Lee is free to love what she wants without the film mocking her for it, sending a message to young, female audiences that they too should feel no shame for their interests.

When Lee first transformed into a red panda, she frantically hid in the bathroom. Assuming that Lee was experiencing her first period, Lee’s mother presented her with a box of menstrual pads.

Some reviews condemned the film for its inclusion of “adult topics like puberty and menstruation.”

But puberty is a universal stage of life that every child goes through. Girls most commonly experience puberty around ages 10 to 14 and most get their first period around 12 years old. Despite this, teen-exclusive experiences are considered mature topics that are only appropriate for adult audiences.

Society upholds an unhealthy stigma against menstrual cycles. Although it is a significant part of life for half the world’s population, periods have remained a taboo subject and are hardly mentioned in movies and TV shows. And when they are actually mentioned, mainstream media has looked upon the natural process with shame and disgust.

“Turning Red” approaches this stigma with a refreshing breath of normalcy as Lee’s mother firmly assured Lee that periods were common, there was no need to be scared or embarrassed and everything would be okay. Lee’s mother also introduced period essentials such as ibuprofen, vitamins and a hot water bottle to Lee, thus normalizing a common experience for many young people.

Critics also bashed the film for glorifying disobedience and encouraging kids to rebel against their parents, but throughout “Turning Red,” Lee deeply honored her parents and ancestors. She did not want to rebel but ultimately had to choose the freedom to be herself — a valuable lesson for young audiences.

Condemning Lee for her disobedience largely ignores the fact that Lee was rejecting the idea of sealing her authentic self away completely. Lee was both developing and accepting her sense of self while critics seemed to forget a handful of disobedient characters like Nemo from “Finding Nemo” and most Disney princesses like Ariel from “The Little Mermaid.”

While most of the film’s controversies lie in its themes of growing up, some also criticized “Turning Red” for being unrelatable.

Sean O’Connell, CinemaBlend’s managing director, said in a since-deleted review that “Turning Red” was not made for universal audiences because the film is rooted “very specifically in the Asian community,” making its target audience “very narrow.”

Until recently, Disney has always featured predominantly white characters while people of color remained severely underrepresented. While Asian viewers identified with Lee for cultural reasons, others related to Lee’s teenage cringe-worthiness and family dynamics. Although O’Connell apologized for his review after intense backlash, it is clear he centered white perspectives as the universally relatable narrative.

“Turning Red” and its criticisms teach filmmakers and audiences a very important lesson: The experiences of young teen girls should be normalized both on-screen and in-person. It is time to put an end to the media’s inaccurate and harmful depictions of teenage girls and open conversation to unreasonably stigmatized topics. As young girls navigate through new thoughts, feelings, interests and bodily changes, it is important for these stories to be told without shame.

In all of its complex, weird, hormonal and heart-wrenching glory, “Turning Red” embraces what it’s like to be a teenage girl simply as it is: normal.