National Braille Press creates new technology for blind community in 21st century

May 12, 2022

A white classic colonial style building on St. Stephen Street in Boston’s Fenway district holds some of the most innovative and collaborative work for the blind community.

The National Braille Press, or NBP, creates braille resources for blind people in the United States and beyond with the mission to empower the blind community.

In 1927, the organization was founded by Francis Ierardi, a blind immigrant from Italy and student at Perkins School for the Blind. He recognized the lack of news access for the blind and created a place that could offer braille news for blind people in a more timely manner.

The purpose and mission of NBP expanded after settling into their current location in 1946. The organization now creates braille textbooks, tests, menus and manuals for all of North America.

Joe Quintanilla, vice president of development and major gifts, is in his 11th year with the National Braille Press. He emphasized the importance of creating resources that are accessible and affordable for blind people.

“It generally costs three times more to produce a book in braille than it does in print,” Quintanilla said. “We believe that a blind person shouldn’t have to pay more for the same information that’s available in print. The money that we raise helps offset that difference.”

Brian Mac Donald, president and CEO of NBP, said NBP wants to keep up with technology movements while also sticking to its roots of providing blind people the resources for them to go through everyday life. Mac Donald came to NBP in 2008 with the intention of developing the digital aspect of the braille world. He wanted the organization to continue to survive as a print resource while adapting to the changing times.

“We still produce millions of pages of paper braille every year,” Mac Donald said. “And we will continue to do that as long as there is a demand for it for many, many more years to come… but we certainly want to continue to have digital equipment that’s affordable and keeps current so that blind people can keep up with sighted people in terms of technology.”

NBP publishes its own materials for the blind, by the blind, about how to use technology such as phones, apps and devices.

“It is … a way for a blind person to learn from the experience of a blind person [about] how to use technology because then it empowers them to be independent to learn how to use computers and be able to find a job,” Quintanilla said.

Mac Donald’s main technological initiative at NBP was creating refreshable braille displays. These allow braille notetakers to process words into text on screen and also read through raised text on a monitor’s output. They were originally priced anywhere from $6,000 to $10,000; however, this was unaffordable for many blind people.

“Schools had trouble funding them. It was just a nightmare. One of our goals was to see if we could create a lower cost professional braille product that had more features,” Mac Donald said.

Mac Donald partnered with over 25 volunteers in the community to create more accessible technology. One product, called the B2G, is a portable, lower cost, refreshable braille computer for the blind.

“We wanted to make sure blind children and adults could have access to digital braille at a much more affordable rate. [Braille technology] could … level the playing field for accessibility,” Mac Donald said.

Mac Donald and NBP sold the first product in 2016 for a competitive $2,495. By 2019, they cut the price in half and today, they have new technology for less than $500, according to Mac Donald.

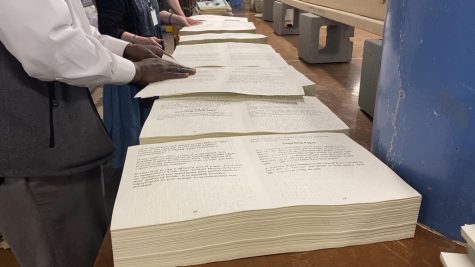

While the board and leadership create these products and imagine the future of braille technology, much of the production work continues with books and paper resources in the basement of the building where NBP employees and volunteers personally bind all of these resources.

George Kamara, a part-time staff member, became blind at 30 years old. As a refugee from Liberia, he wanted to get his associate degree but needed to take the GED test in order to apply. He spent four years learning braille to take a braille GED. Today, he collates all materials sent out to the community similar to the textbooks and exams that helped him progress as a braille reader.

“We want our voices to be heard. I was not born blind in the first place,” Kamara said. “I had to learn to read and write braille and it has really helped me a lot. When I came over to the braille press as an intern, it created more interest to be an employee. It has made me so happy … I hope to do my best to reach other people through this organization.”

A more recent mission of the organization is to bridge the gap between blind and sighted children and parents with a monthly children’s book club. According to Mac Donald, the National Braille Press wanted to make children’s books available in print and braille to allow families to read together. This evolved into creating tactile graphics, which allow blind children to feel shapes and animals on a page.

“For early readers in primary grades, that’s how they become literate,” Mac Donald said.

“That’s how they learn grammar and spelling and that’s something you can’t do with just listening either.”

NBP takes pride in the clear impact of these changes and the book club. Quintanilla met grandparents who are now able to read children’s books and create the same connections with their grandchildren as sighted families.

“The National Braille Press has the pulse of the blind community and tries to serve the need,” Quintanilla said.

The organization welcomes volunteers from elementary school to college-aged students in Boston. Samantha Bowman, a third-year mechanical engineering and business administration double major at Northeastern, started with the National Braille Press in her first year at Northeastern through the Alliance of Civically Engaged Students partnership program.

“NBP gave me a better understanding of what to take into consideration in order to make material truly accessible to all and it is something I can apply to all parts of my life going forward,” Bowman said. “NBP is working hard to make their name known and support strong outreach programs in the digital age, ensuring they can reach even more people in need of their services.”