Boston’s Little Syria: How a forgotten community lives on today

A display case in MIT’s Rotch Library shows remnants of Boston’s Little Syria. The neighborhood, once located between the South End and Chinatown, disappeared in the 40’s and 50’s as Syrian immigrants moved to suburbs. Photo courtesy of Lydia Harrington.

January 2, 2023

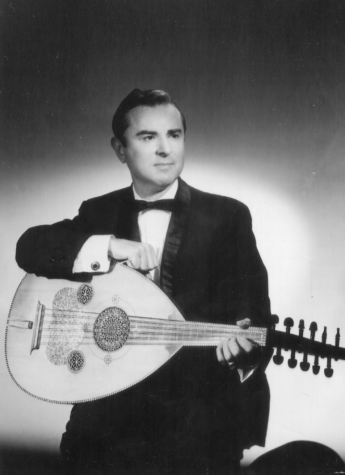

Few students who study in the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Rotch Library pause to look at the unassuming array of tables and books. However, upon closer inspection of a display case on the second floor, a wooden Arabic instrument inside a glass box reveals part of the complex and lost history of the Syrian community in Boston.

The pear-shaped stringed instrument, called an oud, was owned by the late Arabic singer Anton Abdelahad, a resident of Boston’s Little Syria. Abdelahad’s oud and his story are part of an MIT exhibit, opened Dec. 1, that chronicles the near-forgotten history of the neighborhood. Syrian instruments, letters, pictures and sheet music fill an otherwise unextraordinary space with the legacy and stories of thousands.

“In the beginning for us, [we were] just thinking about… how [we can] understand the context of larger patterns of migration from the Ottoman Empire, and specifically Lebanon and Syria, to Boston and … the Americas,” said Chloe Bordewich, a postdoctoral fellow at Boston University and historian of the modern Middle East. “We’re historians; our families are not from this neighborhood, but we know the big picture enough to be able to connect it to these families, who have been generous in sharing their stories with us.”

Through oral histories, Boston census data and familial interviews and heirlooms, Bordewich and Lydia Harrington, a postdoctoral fellow in the Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture at MIT, curated the exhibit to create an interactive, tangible way to explore the past of Middle Eastern communities in Boston.

“One large point of the exhibition was to show real visual evidence of the neighborhood as it was,” Harrington said. “We had been in touch with families we found through local churches … and we talked with them a lot to find out their specific experiences, or to research specific people who were major figures in the neighborhood.”

One of these notable figures was Abdelahad, whose music appeared in famous movies such as “Pulp Fiction.” He performed for the king of Saudi Arabia and became, at the time, one of the most popular Arab performers in the country though appearing in concerts and music festivals.

Abdelahad’s parents, his father Assad Abdelahad and his mother Ramza Abdelahad, immigrated to the South End from Damascus, Syria as teenagers in 1902 and 1904, respectively.

“My father’s mother was 15 years old when she came to the United States. She was very well educated in the Middle East, a kind of prodigy,” said Sharon Abdelahad Wall, Anton Abdelahad’s daughter and a 1973 Northeastern alum. “Her mother had looked into a pre-arranged marriage … so [Ramza] appealed to her dad and said, ‘My sister is in Boston, they want me to come. They are running a business and would like me to go to America.’”

Both Ramza and Assad Abdelahad arrived in the United States, like many who immigrated from the Middle East at the time, seeking greater opportunity. On Nov. 25, 1905, the couple married and moved to the South End.

The people that immigrated to Boston, mostly from the region between Damascus, Syria and Zahlé, in present-day Lebanon, came from varying economic backgrounds and were nearly all Christian, with denominations of Maronite, Melkite or Orthodox.

Between 1880 and 1930, thousands of Syrian and Lebanese immigrants moved into Boston’s South End and today’s Chinatown, forming a small neighborhood labeled “Little Syria.” Fleeing economic hardship, Ottoman military conscription during World War I, religious persecution and the 1860 Mount Lebanon civil war, “Little Syria” communities popped up throughout the United States. According to the Boston Globe, by the 1930s, as many as 40,000 Syrians lived in Massachusetts, and despite immigrating to the United States for various reasons and from various backgrounds, there were similarities among families within the Syrian and Lebanese community.

“When people started coming between the 1880s and early 1900s, people would come with their families,” Harrington said. “Usually, [they lived in] buildings with four to six apartments, and one bathroom which was outside before they got indoor plumbing.”

Ramza and Assad Abdelahad settled in one of these buildings on Hudson Street, where they had three children: Evelyn in 1908, Anton in 1915 and Charles in 1918. Not soon after, in 1927, Assad Abdelahad died at 43 years old, requiring the Abdelahad children to provide for their family as teenagers.

For 15-year-old Anton Abdelahad, coming from an impoverished family compelled him to take up an early profession in music. Though this was unconventional, as most Syrians at the time worked in the clothing industry, Abdelahad’s interest in music helped provide for his family and would soon elevate him to become a notable figure in the world of Arab music.

“[Anton] took great pride in coming back from … functions and bringing his pay and giving it to his mother because they struggled,” Abdelahad Wall said. “He was someone that was very much sought after. His popularity grew exponentially, and [his uncle] would accompany my dad and take him to the various venues where he was being asked to perform.”

As Anton developed his musical talent, his mother ensured his knowledge of Arabic, teaching him how to write and speak the language after he would come home from school.

Shoulder to shoulder with other immigrants, Little Syria was “never 100% Syrian,” Bordewich said. Buildings in the neighborhood housed Syrians, but also Greeks and Armenians. Syrian children sat in classrooms with Irish, Chinese, Jewish and Armenian students before playing in intercommunal sports leagues after school.

“We found an oral history where one woman said, ‘We could swear in 10 different languages,’” Harrington said. “[The Syrian community] was definitely interacting with different types of people, different backgrounds.”

While living in a shared, intercommunal neighborhood, Syrians turned to churches to build support from within the Syrian community. St. George’s Antiochian Orthodox, St. John of Damascus, St. Mary’s and Our Lady of the Cedars of Lebanon all provided a place for the Syrian community to gather and support each other as the community grew throughout the early 1900s.

“The churches were places where people could speak their language, celebrate holidays, find people to date and marry and socialize,” Harrington said.

In affiliation with social organizations, churches also worked to provide students with scholarships, help grieving families and organize fundraisers to provide aid to Middle Eastern countries facing conflict.

For the Abdelahads, the church provided a means for the family to assimilate into Boston, and eventually as a way for the family to give back to the same community that had welcomed them.

“The church was a huge, huge piece of all of [our family’s] lives,” Abdelahad Wall said. “[Our grandmother] was very active in terms of helping people in the neighborhood through the church.”

Anton Abdelahad rarely attended church with his family, as he spent ample time away from home touring the country. But, by the age of 19, Abdelahad’s name and oud playing ability appeared throughout newspapers as he performed in dramatic productions, haflat (concerts) and mahrajanat (multi-day music festivals).

With Abdelahad’s fast-tempo and authentic Arabic music entertaining Middle Eastern audiences throughout the country in the ‘30s and ‘40s, he was able to move out of his parents’ home to live with his wife in 1940 and start his own record label in 1947. Ramza Abdelahad would eventually sell her home and move to Somerville.

In fact, at this time, many families started to move out of Little Syria and into the suburbs. Highway and university construction, development of condominiums and upheaval due to the Boston Redevelopment Authority’s urban renewal program forced many families out of Little Syria into the outskirts of the city. By the mid-20th century, Little Syria was no longer filled with Syrian residents, restaurants and churches. Those who stayed in the neighborhood often owned the buildings they once rented.

“The demographics shifted overtime and, by the ‘40s and ‘50s, you are seeing new groups of immigrants who are coming in and… [now] renting from the Syrians,” Bordewich said. “The Syrians are no longer the ones renting from the Irish, Italian or English owners.”

Additionally, a desire for suburban life outside of the city led to the beginning of the end for the neighborhood.

“People in the community [found] more white-collar jobs, like doctors [and] teachers,” Harrington said.

“[It was] part of a pattern of immigration in U.S cities, [where immigrants] would move to the suburbs or further out to get a bigger home, a quieter place.”

As the salience of Little Syria wound down in the late 19th century, so did Abdelahad’s time performing. A heart attack late in life nearly ended the singer’s career, but reminiscent of the resilient community he grew up in, Abdelahad continued to perform.

Throughout his performing career, Abdelahad, if he were home, would sing a special chant, known as Inilbaraya, during the Lenten season preceding Easter. But due to his heart attack, many churchgoers and family members thought Abdalehad would never perform the chant again.

However, when a churchgoer at St. John of Damascus Church asked Abdelahad to join the choir in the very same chant, he could not pass up the opportunity. And though his heart attack resulted in a severe loss of heart function, the 70-year-old singer performed his solo with choir anyway.

“[My dad] lost two thirds of his heart function with the attack, and he thought he would never, ever sing again,” said Arthur Abdelahad, Anton’s son and a 1968 Northeastern alum. “He grabbed my hand… walked to the back of the hall where the choir was — the priest did not know this was going to happen — and he sang for the church.”

Anton Abdelahad died in West Roxbury Dec. 25, 1995, but his music continues to be played in Arabic settings throughout the world.

Today, remnants of the community can be found in the Syrian grocery stores and restaurants on Shawmut Avenue and within the churches that moved with the community out into the suburbs. Restaurants, holidays and festivals maintain the sense of community that enriched the lives of those who lived in Little Syria.

“The community is still there,” Arthur Abdelahad said. “Unfortunately, with every generation, it gets a little thinner, but that’s the way it is. But my children, we’ve embraced the food … the traditions and our children still feel the love and embrace their heritage.”