Following the August release of a statewide database of police disciplinary records, two of three Northeastern police officer records have been amended in an effort to correct the original publication.

The Massachusetts Police Peace Officer Standards and Training Commission, or POST Commission, faced controversy after its database of statewide police officer disciplinary records was said to include inaccurate records. No specific details were mentioned in POST Executive Director Enrique Zuniga’s interview with the Boston Globe on what sparked removal and revision of more than 49 complaints, but POST released a statement acknowledging its error.

“Note that POST is planning the release of additional data. We continue reviewing requests for corrections and/or updates and will append to the database on an ongoing basis,” the statement on their website reads.

The POST database was created to uphold the 2020 criminal justice reform act, which aimed to further accountability from law enforcement by requiring every Massachusetts law enforcement agency to release disciplinary records for all employed officers. The act also mandates public involvement in the commission, increasing safety and education through public forums and information sessions.

The database includes officer records dating back to December 1984 and up to January 2023 from 273 departments around the state, including campus police departments. Officers who have resigned or retired in good standing are not included but displayed in the database are those who have retired or resigned to avoid discipline. Complaints range from minor misconduct resulting in short-term suspension to complaints concerning deadly force.

Included in the Sept. 1 changes to the database were updates on the categorization of complaints against two Northeastern University Police Department, or NUPD, officers.

Complaints against Jason Grueter, an NUPD officer initially said to have had two counts of misconduct related to bias on the basis of gender, have been changed to one count of bias on the basis of gender. Brenda Zirpolo, an NUPD officer who originally had one allegation under the ‘alcohol or drug abuse’ subtype, is now categorized for one count of ‘other/conduct unbecoming.’

James Witzgall, the third NUPD officer on the database, did not have any changes made to his five allegations of ‘conduct unbecoming,’ all of which occurred before he joined the NUPD.

According to POST reporting requirements, ‘other misconduct’ refers to violations which fall under unprofessionalism, policy, conduct unbecoming or conformance to rules. Both Grueter and Zirpolo faced short-term suspensions, the typical result of these offenses.

The language of ‘other/conduct unbecoming’ is vague, but possible examples include speaking disrespectfully to a supervisor or citizen, using profanity, lying to a supervisor or any type of misconduct that does not fall under the umbrella of an existing category and goes against individual department standards, according to several department websites.

The POST Commission released a second update Sept. 19, a month after its initial rollout, allegedly correcting certain items and adding information and fields to provide additional information, according to its statement. Neither of the NUPD officer entries were updated further, and are still categorized under ‘other/conduct unbecoming.’

Compared with other campus police departments, Northeastern had one of the lowest numbers of officer disciplinary records in the database. Boston University’s Police Department had 13 officers in the database and Harvard University’s Police Department had 77, placing them as the department with the fifth-highest number of complaints out of all departments included in the report. They also had the highest out of all state campus police departments, with complaints against 30 officers.

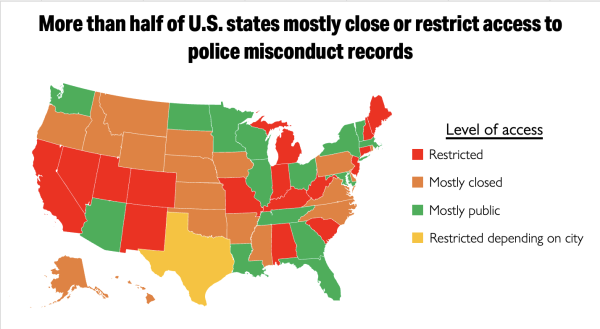

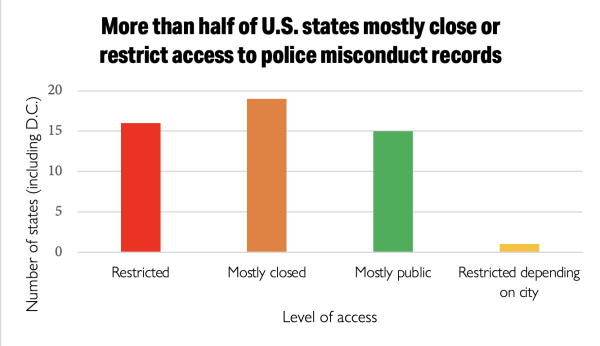

Massachusetts is one of the few states nationwide that has its police records accessible to the public. A 2022 AP News report, funded by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, analyzed police misconduct record laws in all 50 states. The results showed many states are still fighting to add this level of transparency.

According to the report, 36 of 50 states have either mostly closed or restricted access to police misconduct records. Some states were able to increase access in recent years due to public demand, as seen in the following descriptions of how some states’ accountability efforts paid off while others are still working.

The Freedom of Information Act, or FOIA, grants citizens the right to request records from any federal agency. FOIA guidelines say that agencies should only withhold information if they “reasonably foresee that disclosure would harm an interest protected by an exemption.”

In Massachusetts, anyone can request public records without a statement of purpose. Some states, including Massachusetts, have their own public record laws which give the public a wide range of access to obtaining public records such as police misconduct data. Other states are still navigating the path to increased transparency.

Misconduct records have been historically closed in New Jersey, but a winning 2020 decision in New Jersey’s appeals court decided records would open for officers facing discipline for instances of extreme misconduct, including use of force or domestic violence. However, the state’s Supreme Court ruled in June 2023 that people who sue for public records under New Jersey’s common law right of access have to pay for their own attorneys regardless of the case outcome. This means that although police misconduct records are accessible through public request, without included coverage of attorney fees, most members of the public would not be able to go through with pursuing the records.

In New York, officer misconduct records became public in August 2020 after heightened public distrust of the police and nationwide protests persisted following the murder of George Floyd. New York’s police unions vehemently opposed the change, even banding together to sue the state, but were unsuccessful in preventing multiple decades worth of records from being released.

Twelve states aside from Massachusetts provide what is known as an integrity bulletin, a database of officer disciplinary records. However, not all of the 12 states provide officer names like the Massachusetts POST Commission does. The 12 states include Arizona, Minnesota, Connecticut, Montana, Florida, Oregon, Idaho, Utah, Indiana, Vermont, Kansas and Washington.

As efforts to increase police accountability continue to grow, specific state laws concerning access to police records will continue to change. Consulting local law enforcement agencies on their legal requirements ensures the most up-to-date information on these changes.

Massachusetts continues to show its growth in being a driving force behind police improvement via public involvement. Governor Maura Healey and Attorney General Andrea Campbell announced Sept. 12 that two new members were appointed to join the POST’s licensing and oversight commission, including Worcester Reverend Clyde Talley and Deborah Hall, head of YMCA Central Massachusetts.

“It’s clear that over the past three years the commission has laid the foundations for strengthening accountability and trust in law enforcement, and I’m eager to continue building on that work,” Talley said during the appointment.