“Stand Up If You’re Here Tonight” subverts expectations at every turn. The play doesn’t rely on conventions; it rejects them. It’s as tragic as it is comedic, and it’s this level of nuance that makes this performance both impossible to categorize and a deeply impactful experience.

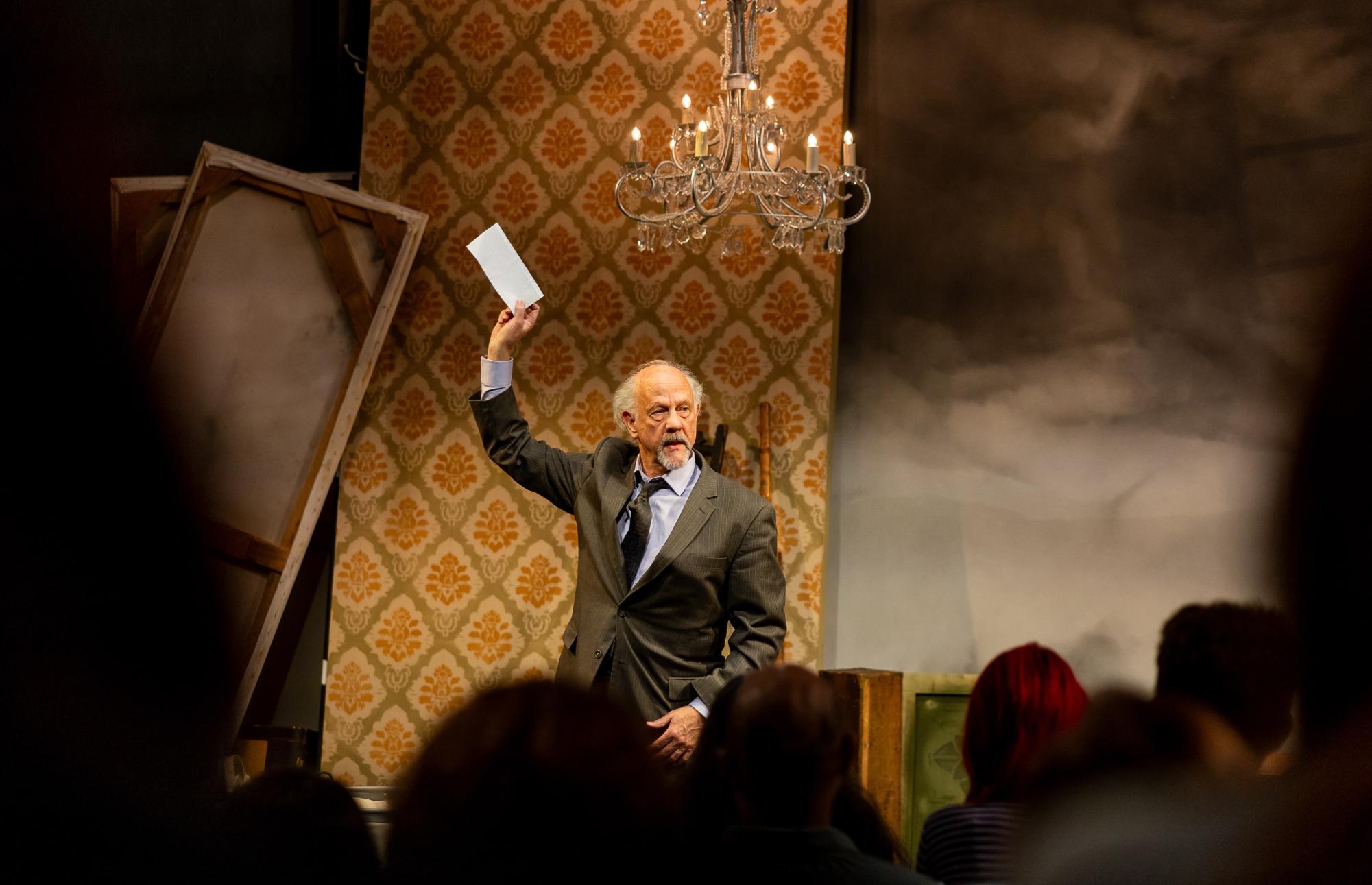

“Stand Up If You’re Here Tonight,” or “Stand Up,” began its run at The Huntington Theatre Jan. 20 after premiering at the Circle X Theatre in Los Angeles and the Harbor Stage Company in Wellfleet, Massachusetts three years earlier. The production is currently housed in the theatre’s Maso Studio, a deeply intimate space that seats only 150 people. For other productions, the limited space and seating may be viewed as a detriment, but for “Stand Up,” it only enhances the experience.

The play is a portrait of loneliness born out of the isolation of the COVID-19 pandemic. In spring 2021, playwright John Kolvenbach found himself reflecting on his relationship with theatre and what he hoped to see in a play.

“That hope is to lose myself to the play, to lose the boundary between the play and myself,” Kolvenbach said. “[I] got to the idea that you could write a play that was essentially a romantic play about the audience and the play itself.”

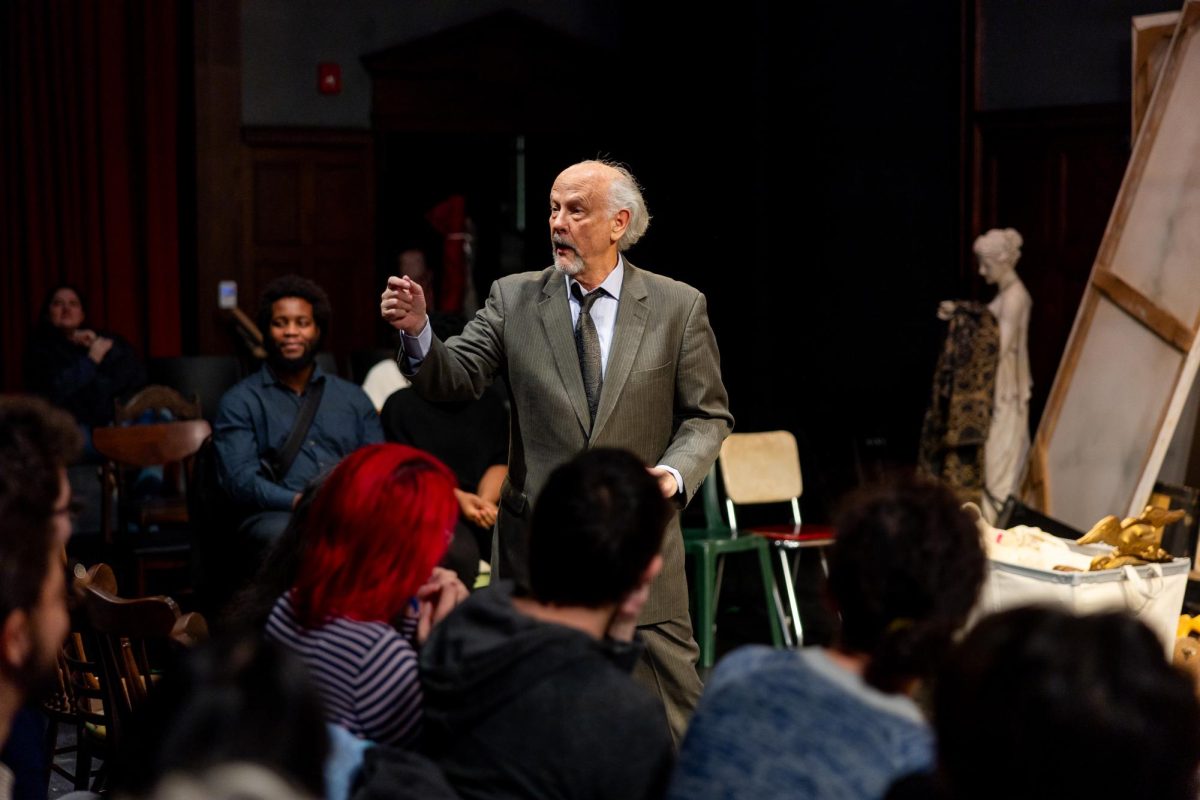

To Kolvenbach, what makes “Stand Up” so unique is its direct reliance on audience engagement. The play is a one-man show, which performer Jim Ortlieb leads entirely. His character’s name is never mentioned, and this sense of anonymity allows for a deeper connection with the audience. Ortlieb spends most of the performance talking directly to the audience in moments that range from feeling like a therapy session to an interrogation.

Kolvenbach’s son, Baker, has seen the play in several iterations and has been able to observe Ortlieb’s balance between irony and sincerity in each one.

“Obviously, the stuff that Jimmy is doing is tongue-in-cheek, but at the same time, I think there is probably some kernel of earnestness,” he said. “You think that you’re not supposed to take any of it at face value, but probably some of it is actually what he’s trying to say.”

Because the play hinges so heavily on audience engagement, Ortlieb’s performance is different every time to match the audience’s energy. Navigating this shift in environment can prove to be a tall order.

“You need an actor like Jimmy to be alive and allow it to be flexible,” John Kolvenbach said. “It’s very difficult to do … and that’s what allows the show to be different.”

Ortlieb’s efforts to reach the audience span beyond his thought-provoking quips and questions. In moments of engagement, he calls upon audience members to answer a question or read something aloud. In others, the whole audience must clap its hands, sigh together or sing a certain note. The result of his character’s desperate attempts to draw closer to the audience is that its members are pulled towards each other.

“When a human being has that need to come out here in front of a group of people and to try to connect with each and every one of them, there’s something going on with that fellow,” Ortlieb said.

Bearing the weight of the play and its audience alone might seem like a lot of pressure, but Ortlieb manages it with ease. While his character’s sardonic ramblings and witty remarks reveal the wry humor of John Kolvenbach’s script, Ortlieb’s well-realized delivery elevates them. The same goes for the moments of tragedy. As Ortlieb’s character begins to connect more deeply with the audience, a chasm of longing is revealed beneath the surface. This insatiable desire for connection is the result of desperate loneliness and the fear of isolation.

What makes this desperation for connection resonate so deeply with the audience is how universal Ortlieb’s portrayal of these emotions feels. Details about his character’s past are mentioned here and there to provide context about why he is experiencing such despair, but how this yearning for a meaningful bond is conveyed allows it to ring true with each individual audience member.

When asked what makes his character so universal, Ortlieb lifted a line directly from the script.

“I think you know who this guy is — it’s you,” he said.

John Kolvenbach elaborated on this point by emphasizing how, although the challenges that each person experiences are different, there is a universal desire for companionship.

“We’re all individuals, obviously, but we share as human beings a need for one another, and that’s one of the things that the play, in its own humble way, is trying to achieve,” he said.

“Stand Up” also directly acknowledges the struggles of everyday life that contribute to a lingering feeling of needing to connect with others. The play opens with a sequence where Ortlieb’s character jokes about the process that audience members had to go through to get to the theatre. The man’s ramblings parallel what he imagines much of the audience must have been thinking, but there’s an underlying heaviness to it that denotes a dissatisfaction with everyday life.

“We walk through life in a Kafkaesque world that we agree with and that we want to live in, and we don’t come out of our shells,” Ortlieb said. “One could be dulled by the mundane nature of everyday life or by the horrors of everyday life, but we shouldn’t lose our humanity and our need to connect.”

The play’s title takes on multiple meanings throughout. At several points, the audience is encouraged to stand up if they’re “here,” but the true meaning of “here” evolves throughout the show.

“The play is a lot about being in the moment, being present, allowing yourself to actually be where you are undistracted,” John Kolvenbach said. “Presentness is vanishingly rare, and … that is what I want and also what I am running from all the time, ironically.”

This demand for being in the present encapsulates why audiences may feel uncomfortable at first. The play’s confrontational and, at times, existential nature commands the audience members’ attention and challenges them to think more deeply about who and where they are.

“Part of the purpose of the theatre is to give us an opportunity to let everything else fall away and all the petty requirements of living this life and to have a moment, an hour in this case, hopefully, to think about things that are richer and deeper and more essential,” John Kolvenbach said.

Performances of “Stand Up If You’re Here Tonight” at The Huntington run until March 23.