By Cassidy DeStefano, news editor

Imagine two island nations occupying the same area of the sea – one prosperous, one desolate. The well-off country, home to 1,000 people, welcomes two asylum seekers from its counterpart, who crossed a stretch of ocean to escape the bleak conditions of home.

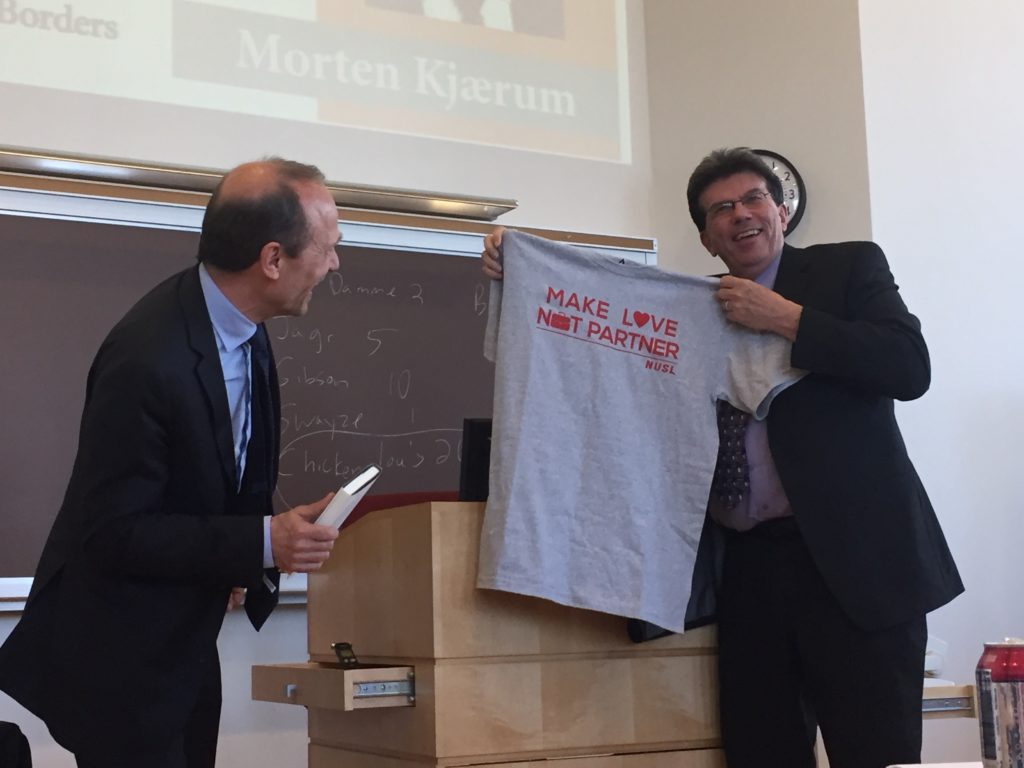

Human rights activist Morten Kjærum said that this proportion, one refugee per every 500 residents, accurately reflects the scale of the migration crisis that European Union (EU) leaders say will overcrowd the 28-state territory. Still, he proposed in Wednesday’s keynote address for Northeastern University’s (NU) “Transcending Borders: Migration and Human Rights Week” that the reason for deadlock is not rooted in population but in racial and ethnic discrimination by country leaders.

“Discrimination and hate crime is all about seeing our fellow human beings in singular identities,” Kjærum said. “The human rights approach recognizes that every person is a unique individual in their complexity in multiple identities.”

Kjærum’s talk was one of six events comprising the weeklong agenda, which ran April 7-14. The forum, co-hosted by the Northeastern University Law School (NUSL) and groups including the Black Law Students Organization and Human Rights Caucus, aimed to “examine the global migration crisis from a human rights perspective” according to NUSL’s website.

“Human rights, despite its many contextual problems, is a lens through which the status quo can be challenged,” NUSL Dean Jeremy Paul said.

The lecture itself honors NUSL Class of 1993 alumna Valerie Gordon, who died in an accident.

“In the spirit of Valerie Gordon, Europe needs to have that new vision embracing all its citizens, wherever they live,” Kjærum said. “That goes for the Syrian refugee, the child of the immigrant living in the suburbs of Paris, the poor working European.”

Kjærum, who launched his career at the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA), said that the three major terror attacks in the EU over the past year – two in France and one in Belgium – have caused European political leaders to cling to the concept of “the Christian state” for fear that opening country borders will invite Muslim jihadists.

“We have some very nasty, very xenophobic rhetoric from the Eastern and Central European states,” he said. “Today in Europe, you find a much stronger group of right-wing extremists numbing a good group of otherwise constructive parties within the member states.”

Another reason for the stalemate, Kjærum said, is what he called a “new phenomenon” in immigration to Europe over the past 50 to 60 years. Some audience members, including freshman law student Hannah Eash-Gates, disagreed on this point.

“I’ve been working in the immigration field and the human rights field for a long time,” she said. “I thought what he had to say was interesting, but I would argue that there’s a very long history of multiculturalism and immigration in Europe.”

To illustrate the discrimination problem, Kjærum interviewed members of 23,000 ethnic minorities in the EU in 2009. The survey, which will be recast in 2017, indicated that a quarter of respondents said they had experienced a hate crime within the past year.

“The union was created in 1952 and for all these years has created an area of peace and prosperity,” he said. “Can all of this just be done away with because of refugees seeking asylum in the territory?”

A 2010 survey of young people in France, Spain and the United Kingdom also indicated a socioeconomic division in the area. Kjærum said that respondents who felt more marginalized were more apt to accept violence as a legitimate political tool.

“What is at stake here is the troubled bond between trust and fear. These two go hand in hand,” he said. “They determine the extent of the social cohesion that we will find anywhere.”

Freshman law student Ivanley Noisette, who was recognized as the annual Spirit of Valerie Gordon essay contest winner for his piece on pan-African and third world involvement in international conflict, said that officials need to take a more global approach to patching up the crisis in Europe.

“When we look at the refugee crisis happening right now, there’s a disproportionate coverage of the impact on Europe as compared to what’s going on in the rest of the world,” he said. “And the ills of the world are not going to solve themselves.”

Photo by Cassidy DeStefano