The Houston Astros won the first World Series title in franchise history last week, and to pinpoint the greatest recipient of credit for the victory is nearly impossible. That said, it’s a worthwhile exercise, not for the assignment or subtraction of glory, but because of the need to understand how teams do and should spend their money in today’s cash-flooded MLB.

The ‘Stros spent $149 million on player salaries in 2017. That ranks around the middle of the pack of MLB, well below the affluent Dodgers (who they toppled in the World Series). How did they win the World Series, then? In today’s baseball ecosystem, in which there’s no salary cap and some teams are equipped to spend far more than others, it is crucial that teams not only spend money, but spend it in the most efficient way possible. The Astros were able to win the Series with a middling payroll because they spent their money in such a way that stretched each dollar far enough to get the job done. Some of it was the product of good fortune, but MLB is becoming a contest of not only who can spend the most, but who can spend the smartest. Let’s have a look at how Houston turned $149 million into a championship.

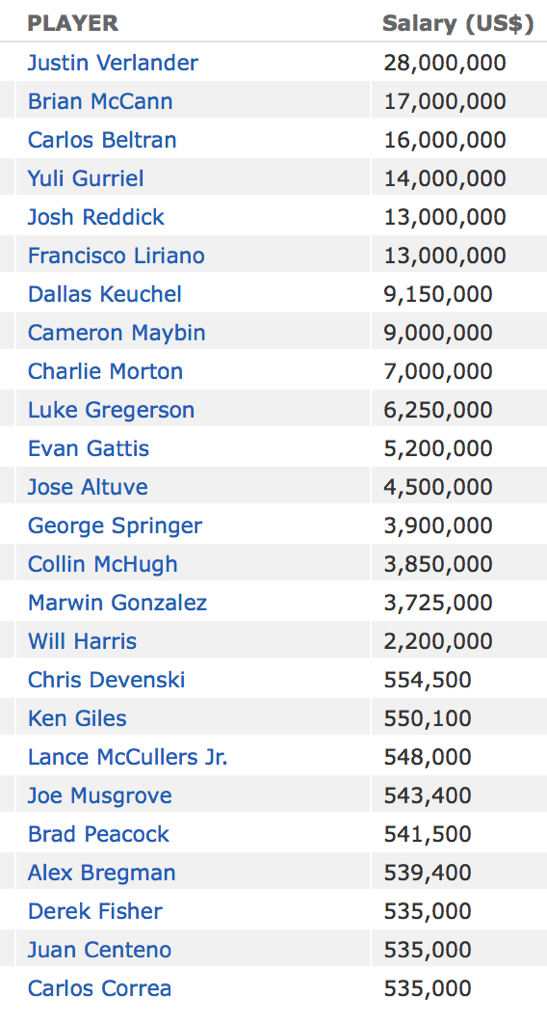

Starting at the top, the $28 million taken home by Justin Verlander jumps off the page. Houston didn’t pay him nearly that much, though, because they didn’t trade for him until Aug. 31st — so the prorated pay would be under $5 million, plus the prospects sent to Detroit. Verlander was a huge addition down the stretch and turned out to be the stopper the Astros needed in their playoff rotation. He threw 36.2 innings in six postseason games, surrendering nine runs and striking out 38. His nine-inning, 13-strikeout gem in game two of the ALCS was crucial in an airtight series against the Yankees. They spent significant assets on a known commodity, a former MVP, someone they could count on to deliver big games.

Brian McCann, the next biggest earner on the team, was a veteran presence behind the plate all year. He’s battle-tested, for sure: tours of duty with the Braves in their contending years and with the Yankees prepared him to be an experienced leader on a team with championship aspirations. He collected 10 hits in the postseason. This is a lot of money to pay a catcher who is in the latter stages of his career and hit just .241 this season, but in addition to providing that veteran presence and contributing defensively, it allowed them to slide Evan Gattis to the designated hitter spot.

Yuli Gurriel, who defected from Cuba at the age of 31 and signed with Houston in 2016, represents a type of payroll allocation possibly unique to baseball, one that many contenders in recent years have utilized. With talent on the traditional free-agent market often overpriced, many clubs have looked to places like Korea, Japan and Cuba to find talent. The Yankees did it with starting pitcher Masahiro Tanaka. The Pirates contended in 2015 with the help of shortstop Jung Ho Kang. And the Dodgers, the World Series runners-up, feature another Cuban, Yasiel Puig, front and center. These signings tend to be gambles, but the Astros’ $14 million bet on Gurriel paid off.

He batted .304 in the postseason with 8 RBI, providing a huge bat in the middle of the order. As mega-contracts for aging, established sluggers (see: Josh Hamilton, Robinson Cano, Matt Kemp) often don’t lead to championships and sometimes spoil plans for years, look for clubs to move increasingly toward international finds like Gurriel to get more out of their money.

Dallas Keuchel and Charlie Morton, much like Verlander, illustrate that it’s important to shell out some cash on pitching. Based on the Houston payroll breakdown, it’s easier to rely on young hitting than young pitching, for the most part. It’s not an ironclad rule, but it’s what the 2017 Astros tell us. Keuchel and Morton each were paid a considerable amount, and they came up big in the playoffs. Morton dazzled in his two World Series appearances, and Keuchel, though not his Cy Young self of old, was a reliable presence throughout October.

They paid the probable AL MVP just $4.5 million — Jose Altuve was a very good player in 2014 when he signed this deal, but has become a perennial contender for the batting title since then. He had a huge playoff, collecting seven homers and 15 RBI. A huge reason the Astros could spend what they spent on pitching was that they had an MVP in Altuve signed to such an affordable deal.

Perhaps the most notable thing about the entire breakdown of Houston’s payroll is the amount of talent at the bottom of it. Several huge contributors took home less than $1 million this season, thanks to baseball’s system of paying young players very little until they’ve played six major league seasons. The Astros benefitted from this dynamic, getting big production at a low cost in many cases.

Young back-end relievers Chris Devenski and Ken Giles faltered in the postseason, but they hauled the mail throughout the regular season and were a big reason the Astros got to the Series. They each made less than $560,000. Lance McCullers Jr., paid just $548,000, tossed 20.2 playoff innings, including a save in game seven against the Yankees, a win in game three of the World Series and a successful start in game seven of that series. That’s elite level playoff contribution, at a dirt-cheap cost.

The list gets crazier as it progresses: Alex Bregman is the fourth-lowest earner on this team and Carlos Correa is the lowest; each earned under $540,000. Bregman hit four October homers and collected 10 RBI, and had a knack for hitting them at the right time — like when he put a dagger in the Red Sox in game four of the ALDS, which the Astros won late to end the series. Correa was the lineup-anchoring monster we know him to be; he clubbed five dingers, racked up 18 RBI and batted .289 in the playoffs. Not bad for the lowest on the salary chart.

From top to bottom, from $28 million to $535,000, the Astros had talent and contribution. They didn’t rely on just the veteran acquisitions or just their young swarm of uprising stars. They got an efficient output from all levels of their payroll.

What does this tell us about how to build a champion in today’s MLB? While you don’t need to spend upwards of $200 million and sign every huge free agent on the market, spending some money on known commodities is a must. Youth and international signings were huge for Houston, but they wouldn’t have gone the distance without Verlander, McCann and Morton.

This also tells us that it’s important to be a little lucky with prospects, in their timing and their success rate. Houston benefitted from a wave of prospects coming of age successfully all at the same time. Correa, Bregman, McCullers Jr., Collin McHugh, George Springer and Devenski all came up through the system and thrived at the highest level simultaneously. This is partly a testament to the Astros’ rebuild and drafting plan, as well as their development system, but it’s also a bit lucky. The best-laid plans don’t often work out this well.

Free agent gambles need to work out, too. The Astros put their trust in Gurriel, an aging McCann and a Verlander who hadn’t been himself lately in Detroit. All three of those ventures turned out nearly perfect.

No team is going to simply buy their way to glory. Even the big-spending Yankees and Dodgers leaned on young, entry-contract guys like Aaron Judge and Cody Bellinger. That said, it takes serious cash to sign established talent, and the more of those a team can get, the better off they’ll be. The Astros used their trove of young talents to form a core, and used their considerable, though not overwhelming, budget to fill in the gaps with smart pickups of quality, established major leaguers. That’s the perfect balance it takes to overcome the ultra-wealthy Dodgers and Yankees and Cubs and Red Sox of today’s baseball universe. It took a perfect storm of planning, decision making and luck. Kudos to Houston.