Every awards season, like clockwork, pundits and film fanatics comb through the perceived frontrunners across the major categories for one thing — a villain. Think “Elvis,” “Green Book” or “Bohemian Rhapsody”: decently-reviewed — if somewhat controversial — films that manage to score key nominations and, in some cases, win over universally acclaimed fare.

This year, it seems, that title has been bestowed upon “Maestro.” Given the musical biopic has endured its fair share of criticism — namely for its makeup and Carey Mulligan’s casting — before opening to mostly positive reviews last fall, this shouldn’t come as much of a surprise.

Though it’s clear why Bradley Cooper’s sophomore directorial effort earned the moniker, the extent to which it has been applied (with some online commentators lampooning it as legitimately awful) appears undeniably hyperbolic. “Maestro” may have some substantial faults, but it is far from the villainous contender that users on film Twitter make it out to be.

Nominated for seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture, “Maestro” charts the tumultuous relationship between celebrated conductor and composer Leonard Bernstein (Cooper) and actress Felicia Montealegre (Mulligan) from the early 1940s to the latter’s death in 1978.

Mulligan is easily one of the film’s greatest assets, perfectly replicating the real-life Felicia’s accent and vocal cadence. Beyond deftly capturing some of her character’s peculiarities in her performance, Mulligan is always emotive and believable, something that becomes gravely important toward the end of the film when Felicia is diagnosed with cancer. In these final scenes, the audience can’t help but feel for Felicia as she weeps, unable to do much on her own anymore — a true testament to Mulligan’s talents.

Cooper, save for one or two moments, fails to match Mulligan, delivering work that, though largely serviceable, pales in comparison. Even worse, his portrayal of Leonard occasionally ventures into unintentionally comedic territory, coming across as something found in a bad “Saturday Night Live” skit rather than a major motion picture.

He is, however, absolutely captivating in a scene set at the Ely Cathedral in England. While conducting Gustav Mahler’s Resurrection Symphony in a practically unbroken take, sweating and waving the baton around, his face radiates pure ecstasy. Scenes like these are few and far between, ultimately culminating in a performance that, overall, is simply fine.

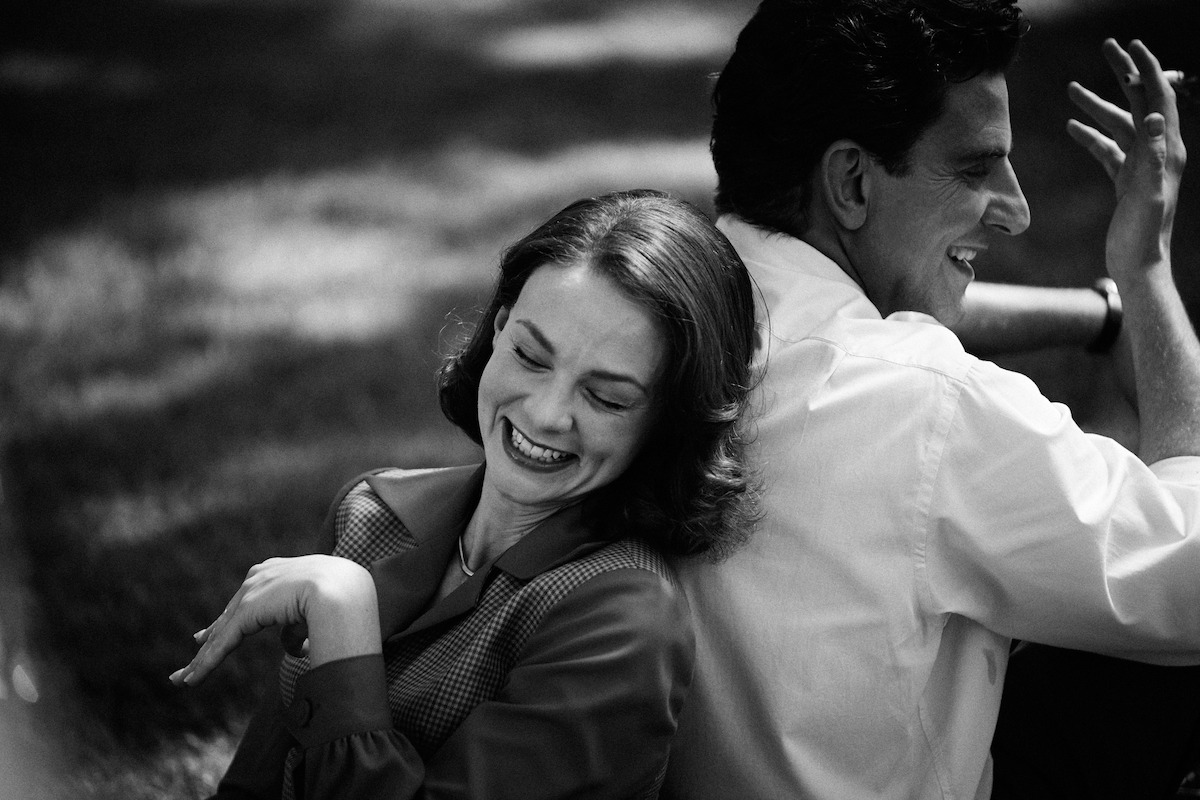

What Cooper lacks in performance, though, is made up for in his directorial vision. Working with cinematographer Matthew Libatique, renowned for his work with Darren Aronofsky, Cooper crafts some of the year’s best visuals: a black-and-white image of Felicia literally trapped in Bernstein’s shadow as he conducts; a gorgeous crane shot capturing the lush landscaping and stunning architecture of the Bernstein abode in Fairfield, Connecticut from far above; and the film’s final close-up of a young Felicia that utilizes striking blue hues in its color grading, amongst others.

Suffice it to say, Cooper’s instincts as a filmmaker have strengthened considerably since his debut feature, “A Star is Born” (2018). However, the same cannot be said for his writing.

The lines uttered by the film’s cast are frequently superfluous, revealing little about the characters and the situations they’re in. Moreover, several exchanges come across as hokey, with the greatest offender — a scene in which Felicia and Leonard attempt to discern what number the other is thinking of — being ridiculed extensively as a result.

Another issue with the screenplay concerns how little information it provides about Leonard’s life, professional or personal. Though this was evidently intentional, with Cooper and co-writer Josh Singer wanting the film to leave the audience with more questions than answers — Leonard’s final line is, after all, “Any questions?” — that does not excuse its ultimate lack of detail.

The screenplay’s superficial nature also leaves some of the film’s ensemble hanging. Take Matt Bomer and Maya Hawke, who play David Oppenheim, Leonard’s former lover, and Jamie Bernstein, Felicia and Leonard’s eldest daughter, respectively; the pair are left out to dry and forced to inhabit characters who are nowhere near fully realized.

Bomer and Hawke can at least revel in the knowledge that they weren’t miscast. Sarah Silverman, on the other hand, tasked with bringing Shirley Bernstein, Leonard’s sister, to life, seems out of her depth. This is increasingly clear in a scene Silverman shares with Mulligan, as the former’s exaggerated vocal inflections and posture make her needlessly stand out, temporarily calling into question the cinematic verisimilitude Cooper and company sought to create.

Because of its flaws, “Maestro” never truly sings, something pointed out by many across social media. However, contrary to what’s been circulating, it can mostly carry a tune.