When Northeastern’s Sexual Health Advocacy, Resource, and Education group and LGBTQA Resource Center were seeking a keynote speaker, Division 1 swimmer Schuyler Bailar was a top pick among the board. Along with a top 15% placement in the NCAA breaststroke category and a Harvard degree in psychology and cognitive neuroscience, Bailar holds the title of the first transgender athlete to ever compete in the NCAA D1 athletic division.

The Sexual Health Advocacy, Resource, and Education group, or SHARE, is a student-led organization making strides to promote bodily autonomy and access to essential healthcare on campus. With a focus on reproductive justice and empowering marginalized voices, SHARE hosts monthly pop-ups, open mic events, fundraisers and weekly meetings to continue its mission at Northeastern.

The LGBTQA Resource Center is a school-administered organization that provides support, resources and community events for students. The center partnered with SHARE to host the March 11 event.

Attendees of the event were thrilled to see Bailar as the chosen speaker.

“I’m queer, and I feel like it’s so important to be able to see someone similar who’s a couple steps further in life,” said Lauren Uhl, a third-year history and political science combined major.

“I’m also queer and have had a lot of reckonings with my own gender. It’s affirming to hear people with similar experiences speak about this,” said Sneha Vaidya, a third-year environmental studies and political science combined major. “[Attending these events are] my way of staying connected with my community. As an Asian person myself, it’s awesome to see an older trans-Asian man speak out.”

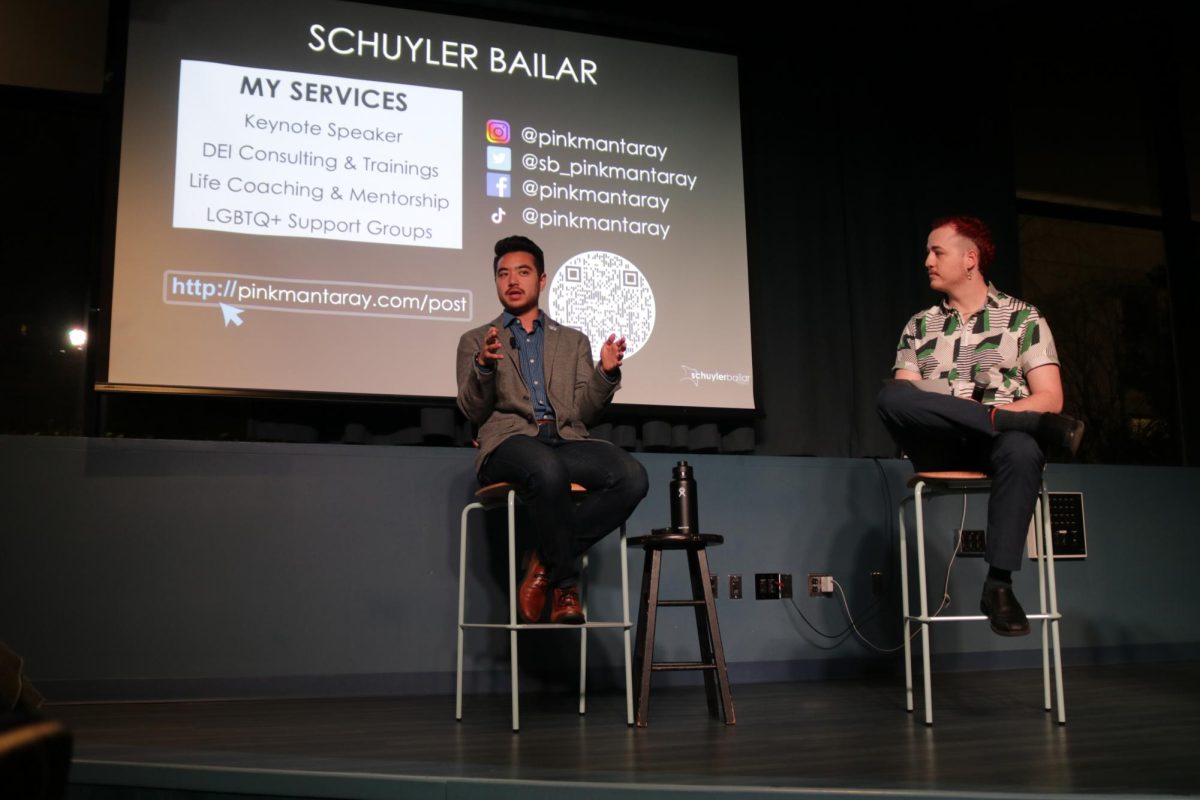

After an introduction from Ari Eiseman and Jay Kemp, SHARE’s treasurer and social media coordinator, respectively, Bailar took the stage.

“Today, I do want to tell you about myself and my story, but what I really want to do is have a conversation together,” Bailar said.

Before he began the interactive portion of the event, which involved taking questions from both Kemp and the audience attendees, Bailar dove more into his background.

Having learned to swim at only 10 months old, Bailar said he has been in the pool his whole life. Despite his later success, Bailar did not consider himself a “winner” until the end of middle school, which he proved by gifting the audience with an awkward young photo of himself dawning a 16th place medal.

“When I got to high school, a lot of things began to change,” Bailar said. “I was always told I was never ‘girl’ enough, and that was okay at first, but over time, it became stressful.”

He described multiple experiences in girls’ bathrooms, being berated by his peers for not fitting into their standards of gender and the subsequent trauma it produced for him.

“I thought, ‘I can’t keep living this way. What can I do to fit in? What can I do to be this woman everyone expects me to be?’” Bailar said.

Eventually, Bailar grew out his hair, began wearing makeup and came out as a lesbian.

“Everything seemed to be falling into place,” he said, showing the audience photos of himself in high school, smiling with winged eyeliner and lip tint. “But in all of these photos, I was miserable. The more I succeeded, the more the disconnection from myself grew, and the more it hurt.”

Toward the end of high school, Bailar broke his back in a biking accident, which impeded his ability to swim — one of his only methods of escape.

Bailar described this period as when his mental health “absolutely deteriorated.” He was soon placed in an eating disorder treatment center in Miami for over four months.

It was there he realized he was not a woman, Bailar said.

He experienced a “deep sense of relief” when finding the word to describe his lived experience: transgender.

“That relief was extremely short-lived and terror quickly ensued; what was I going to do about swimming?” Bailar said.

Bailar’s coach called him in rehab to check in. With some hesitation, Bailar opened up to his coach about his realization about himself.

“I’ve spent all this time trying to be honest with myself; I owe it to myself to be honest with my coach. ‘I am transgender, and I don’t know what that means for this sport, but I know I want to swim.’ After a long pause, my coach responds, ‘I don’t know a lot about this, but this team has recruited you and loves you, and we will find a way for you to swim,’” Bailar recounted.

After returning from the eating disorder treatment center, Bailar underwent a double mastectomy and cut his hair short. Making these strides to move forward as a man opened the door to new questions: What team would he compete on?

In a meeting with the men’s and women’s teams’ coaches, Bailar described this process as a “deeply hard quest to figure out which team was best for [him].”

Bailar underwent mastectomy surgery and met with the members of the men’s team for the first time, finding himself “more safe and aligned with them” than he had anticipated. “Schuyler,” his coach told him, “you know what you want. Take this risk for yourself.”

While swimming with the Harvard men’s team, Bailar secured his spot in the top 15% of NCAA D1 swimmers.

“I want to prove that we can be who we are and do what we love,” Bailar said. “My story is no longer a proof, but a rally and a cry.”